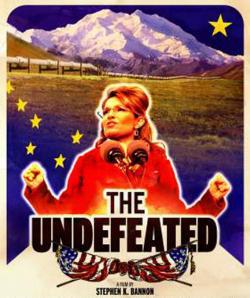

Now that Sarah Palin isn’t a presidential candidate, what happens to people like Steve Bannon? He’d directed a few documentaries before The Undefeated, a warm documentary about Palin, but none that could draw dozens of reporters to screenings—none that could effectively shut down an Iowa town when its subject turned up. Climbing aboard the Palin train, he became a player in the great tabloid drama of the Republican Party: What Will Sarah Palin Do Next?

That train, which has been losing momentum for months, has halted, leaving the chroniclers and inhabitants of Palinworld stranded … somewhere.

Palin’s critics are having the easiest time of it. From the morning in 2008 when Palin was named the Republican vice presidential nominee to last night, Andrew Sullivan wrote tens of thousands of words about Palin’s perfidy, on her “strange lies,” on baseless rumors about her last pregnancy. He welcomed last night’s news with a Madonna video and a pure discharge of bile. “It is hard to describe the relief,” he wrote, “of this awful person finally going away.”

Joe McGinniss, the author who lived next to Palin to write his book The Rogue, was just as relieved.

“I say, ‘whew,’ ” joked McGinniss. “The country didn’t need to dodge a second bullet.” His Palin bio just hit No. 10 on the New York Times best-seller list, right before it became a curio. Was the woman he spent two years writing about no longer relevant? “She’ll always be relevant as an example of how close an utterly unqualified individual came to being only a heartbeat away from the presidency. I’ll gladly sacrifice a few sales to have the country rid of Sarah Palin forevermore.”

But will the country really be rid of Palin just because she isn’t running? After she lost the vice presidency, she was, by default, the biggest star in the Republican Party. That had a lot to do with the idea that she would run for president. When she left Juneau— she’s now been a former governor longer than she’s been a governor—it hurt her image, but it gave reporters hope that she’d run for president. When she spoke to the National Tea Party Convention in February 2010, she turned an ad hoc conference into a national news event, streamed lived on all three cable news networks.

“Then, I thought she was going to run,” said Judson Phillips, the founder of Tea Party Nation, which put on the conference. (He did a Q&A with her onstage after the big show.) “I have been predicting for months now that she would not run. While she remains popular within the Tea Party, any support she had for running had long since dwindled.”

That was a problem. In December 2008, Palin was an unlikely Republican presidential nominee. By 2011, especially after she bumbled her “blood libel” statement on the shooting of Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, the idea of Palin leading the ticket was pure fantasy. It was good for ratings; it was good for traffic. To some degree, Palin will still be good for traffic. But some of the people who covered her will move on. Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank, who spent the month of February ostentatiously refusing to write on Palin, said he had found a new form of distraction: “I only have eyes for the Hermanator.”

But the media’s fantasy was based on something. There were people who told pollsters that they wanted her to run for president. There were people who spent free hours writing at blogs like Conservatives for Palin, which on Wednesday night published items with the titles “Sarah Palin—The People’s Leader.” (“We are collectively faced with the patriotic duty of properly listening to the remaining candidates.”)

And there were people like Peter Singleton, a 56-year-old lawyer from Menlo Park, Calif., who uprooted his life and moved to Iowa to organize for a possible Palin campaign. He became the best-known activist in “Organize for Palin.” He was approached by reporters for hints of what Palin would do with herself, even though he did not personally meet her until the Iowa State Fair two months ago. He lived out of “inexpensive hotels and friends’ apartments.” For his trouble, he heard the news like everyone else did.

“My phone blew up,” he said. “Boom, boom, boom. Call, call, call. And then, like I told the Wall Street Journal, I wanted to have a drink.”

Singleton was happy about how he’d spent 2011. “We were the only grassroots or campaign network that had a bunch of volunteers!” he said. “Everybody else had paid professionals doing their work—we had covered more than 80 county central committee meetings [Iowa has 99 counties] and we often were the only campaign represented. You don’t win the election because of meeting central committees, sure, but we were building good databases. I can tell you categorically, the five best field operatives in the state right now are Organize for Palin operatives who have never done this before.”

Was he angry? No. Would he be moving on? Sort of. He talked about Palin in the same way Bannon did. “This has never been about Sarah Palin as a candidate,” he said. “It’s about the American people, and where we are as a country right now.”

Back in Los Angeles, Bannon’s screening of The Undefeated for the Hollywood Congress of Republicans had gone well. About one-third of the crowd, he said, consisted of Palin supporters. The parts of the movie about the sleazy unfairness of the media weren’t any less shocking. Life was going on, and Palin still meant something, but she’d missed out on something else.

“I do feel that the Republican Party and the movement needs another primary like 1976, when Reagan took on the establishment,” said Bannon. “It’s not gonna be as intense with Palin not in the race. I don’t see that we’ll have quite the fight we were gonna have. Palin could have galvanized us.”