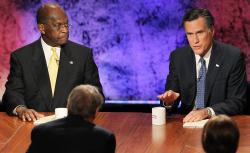

HANOVER, N.H.—When you hold a debate at a boardroom table, the business guys are going to do well. Mitt Romney and Herman Cain were the winners at the Bloomberg/Washington Post debate Tuesday night at Dartmouth College. The eight candidates sat “in the round,” discussing only the economy, which gave Romney a chance to repeat with force the things he says every day on the campaign trail. He spoke confidently about his business career and experience. Cain was amiable, as always, and took every opportunity to mention his “9-9-9 plan.” After this debate, it’s fair to say this plan would be his answer to questions about trout fishing.

This was the first Republican debate after the Great Flirtations. There are no more saviors coming in the Republican Party—Chris Christie, who announced last week he would let this cup pass, endorsed Romney on Tuesday afternoon. If the alternatives to Romney don’t perform better, Republicans should just get it over with and start learning to love him.

Rick Perry has the background and the money to be the alternative to Romney, but he didn’t do much for himself at this debate. For long stretches he seemed to slide under the dining room table. When he spoke, even about an energy plan he is supposed to roll out in the coming days, he was vague and full of platitudes. At such moments, he seemed to be in need of an energy plan.

Perry is running on his success creating jobs in Texas, and this debate could have been an opportunity to give his campaign a boost. He’ll have to make his opportunities in the coming days instead, using his campaign cash to introduce himself to voters as someone a lot more like them than the polished Mitt Romney. Perry’s road to the nomination is probably through the gut. It’s hard to make that kind of connection with voters from behind a polished wood table—and time is running out to make any connection at all.

Cain is a one-note wonder. This is his strength and his limitation. For those who like Cain, he reminded them all the reasons they do. He skips past questions and concerns with confidence: There is no problem, he shows as much as says, that can’t be solved with a good aphorism and good cheer. He doesn’t sound like a politician or a pointy-headed intellectual. When asked about the Federal Reserve Board on which he once sat, he didn’t even sound that knowledgeable.

But does Cain have a second act? Is there more to life than 9-9-9? Moderator Charlie Rose tried to get at the magic behind Cain by asking whose economic advice he relies on. Cain cited Rich Lowrie, a mysterious figure who helped him on his tax plan. When Romney seemed to pat Cain on the head, suggesting the economy needed solutions a little more complicated than Cain’s slogan, it probably drove voters to Cain—We’ve seen what the experts can do, Mr. Romney!—but at some point Romney’s point will hold. There are serious questions about Cain’s plan, and he can’t dismiss them with a smile.

Romney had to defend his support for TARP, which won’t help him with Tea Party activists. Then again, they don’t like him anyway. He is helped in that Gingrich and Cain also supported the bailout. Cain repeated Romney’s answer that TARP was not a bad idea but was poorly executed. At times Cain, who endorsed Romney in 2008, feels like he’s vying to be Romney’s running mate. He’s taken on Perry on his hunting camp and said that he could not consider being Perry’s running mate because of his positions.

Of all the candidates, it’s Newt Gingrich, the self-appointed ombudsman of these debates, who seems to be having the best time. A question is posed and—kapow!—he just wallops the first straw man he can find. Hippie protesters who don’t clean up after themselves, dumb questions from the media, the stupid congressional supercommittee sequestration process: Often none of it has anything to do with anything, much less the questions he was asked, but he’s having fun. And sometimes he’s right on the nose—particularly on the supercommittee. A few more performances like this and he could be the place those non-Romney votes that have moved from Bachmann to Perry to Cain might land for a day or so.

Since the last debate, the early primary and caucus states have moved up their contests by about a month. There is no evidence that has quickened the pulse of Romney’s competitors to knock him down. In the portion of the evening where they could pose questions to one another he got four, the most of anyone, but it gave him only more free time to repeat his forceful positions. Romney appeared to react to the compressed calendar by looking to the general election, talking repeatedly about the middle class. More and more, unless one of his opponents steps up, it looks like Romney is going to be the one sitting at the head of the Republican family table in November.