The scrum of reporters shivering outside the American Enterprise Institute scrutinized every passing SUV, peering at tinted windows for the shape of Herman Cain. He has a week of Washington commitments ahead of him, but he’ll spend Monday avoiding questions about the sexual harassment claims settled back when he ran the National Restaurant Association.

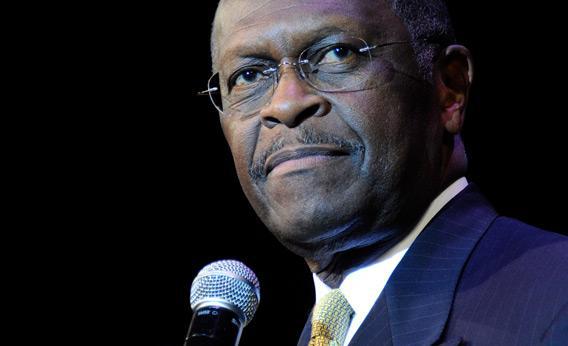

Right at 9 a.m., when Cain was supposed to take a chair at AEI and discuss—ha, ha—his tax plans, a black SUV zoomed into the garage next to the think tank. Reporters chased it down, winter boots clanking, pursued by a security guard who had been watching their stakeout. Cain exited the SUV, wearing a black trench coat and black fedora that would have given him a mien of guilt if they weren’t what he always wore in the cold.

“Do you have anything to say—”

“About the allegations in Politico—”

“Good morning!” said Cain. He was whisked up to AEI’s conference room, where moderator Kevin Hassett warned the crowd that “questions have to be about the topic at hand.”

Going into this, there were worries and tremors about whether Cain would even show up. What was the upside? The story broke at 8 p.m. Sunday. By 10 p.m., his spokesman J.D. Gordon had given Geraldo Rivera an exclusive interview in which he repeated talking points about the liberal media so robotically that he managed to convince the sympathetic host—“[Cain] may deserve much better than this”—that something was up. You could hear the flop sweat plopping through your speakers. By the time Cain was speaking at AEI, his chief of staff Mark Block was telling MSNBC that the story was “questionable at best,” even though the network was confirming pieces of it.

Cain’s task looked difficult. It wasn’t. With presidential frontrunner status comes a sort of reality-distortion sphere, one that lets you avoid answering annoying questions as long as you make it hard to do. With Republican frontrunner status, you get a push-button army of defenders who spring into attack mode as fast as any leveled-up Pokemon. They wanted the story to be dismissed, the media minimized, the official response clear and concise. They would get at least one of these things.

The reality-distorting bubble was impenetrable at AEI. Over a full hour, only one reporter tried to bend Hassett’s rule. Jon Karl of ABC News asked a two-part question, saving the dirty stuff for Part 2.

“As you’re well aware,” he said, “there is a big cloud right now that is affecting your ability to get this out, which is this story in Politico. And I was just wondering if you could clear up for us right now—did you ever …”

“That question is inconsistent with the ground rules of this event,” said Hassett. “He’s going to be at the press club later today.”

“I’m going with the ground rules that my hosts have set,” said Cain. “Now, what was your other question?” Later, he promised that he’ll “take all the arrows” across town, so nobody should sweat it.

Cain finished, and Hassett steered him toward an escape hatch, but the candidate turned back to tell the audience something important.

“Yes, I do have a sense of humor,” he said. “And some people have a problem with that. But to quote my chief of staff, and all the people I’ve talked to around this country: Herman, be Herman.”

What did that mean? Cain headed off to a quiet space to finish strategizing the official response to the story: Answer everything, because he had nothing to apologize for. He was off to Fox News for the first of two interviews on the channel. His economic adviser Rich Lowrie, the maestro of the 9-9-9 tax plan, stuck around for a panel. Most of the crowd, there to see Cain, emptied out. (According to staff, there were already 16 cameramen RVSP’d for the speech even before the story broke.) For an hour, AEI remained home to a parallel universe much like our own, only this was one in which Cain was on track to become president, and no other issues were pertinent. Lowrie lingered to talk to every diehard about the power of 9-9-9. The new scandal didn’t faze him.

“At some point, that story’s going to die down,” said Lowrie, “and then we’ll get back to this.”

One of the fans leaving late, a Tea Party activist and real-estate agent who preferred to use the name “Scout,” dismissed the whole affair, compared it to “the Clarence Thomas attack.” It was unfair, only coming out because “they’re scared of him.” Who, exactly? “The blue team,” she explained.

This wasn’t how it came off on Fox. Cain admitted that the gist of Politico’s story—that there were settlements during his tenure at the restaurant association—is true. But he’d been blameless.

“Yes, I was falsely accused while I was at the National Restaurant Association,” he said. “I say falsely because it turned out, after the investigation, to be baseless.”

He would say the exact same thing at the National Press Club. The place was packed. One staffer performed random checks of the people sitting in the cramped balcony that overlooks the newsmaker luncheon, ejecting them if they didn’t have hard plastic press credentials. Cain easily eluded the rest of the press and arrived to take his seat at the front table, near Block and Gordon. He held up a cupcake with icing that read “9-9-9”— there were cupcakes like this all over the room, most of which disappeared as souvenirs. He showed it off to cameras, grinning, for nearly 90 seconds.

The NPC format (“unchanged since FDR,” boasts NPC president Mark Hamrick) is for the speaker to give a brief address, then take questions curated by the host. Hamrick made the first one an air-clearer about the Politico story.

“I would be delighted to clear the air!” said Cain. He answered, but the air never penetrated his protective bubble. “When the charges were brought,” he says, “as the leader of the organization, I recused myself and allowed my general counsel and my human resources officer to deal with the situation. And it was concluded, after a thorough investigation, that it had no basis.”

This was actually new. In Politico’s story, and in other comments from Cainworld, there was no hint that Cain even knew about the settlements. Hamrick asked Cain if he wanted the National Restaurant Association to clear things up some more. Cain said no. No more questions on the topic. For 30 minutes, Cain returned to his usual role—the straight-talking guy with an adviser for every problem and a silly streak. He let Lowrie swing for him on a tough question on taxes; Hamrick, looking quizzical, let it slide. Hamrick asked him to sing a song, and he actually did it.

Amazing grace will always be my song of praise

For it was grace that brought me liberty

I’ll never know why Jesus came to love me so

He looked beyond all my faults

And saw my needs

And we were done. Cain and his staff retreated to an upstairs room, protected from the rest of the press by bodyguards. Gawkers could see John Coale, the husband of Greta Van Susteren, the Fox News host who’d give Cain his second cleanup interview on the network. Nonmembers of the NPC were barred from going up and over to that area, so that was all the gawkers got. After nearly 30 minutes in seclusion, Cain and his staff headed out, finding a path that takes them away from waiting supporters and reporters.

“Will you answer more questions about the settlements?” barked one cameraman.

“They’ve already eaten up too much of my time,” he said. “Thank youuuuuu!”