A weak front-runner is challenged by a come-from-nowhere candidate wielding a tax plan. Then it was Bob Dole, Steve Forbes, and the “flat tax.” Now it’s Mitt Romney, Herman Cain, and the “9-9-9 plan.” Republicans can be forgiven for having flashbacks to 1996.

Fifteen years ago, one conservative summed up his enthusiasm for Dole by saying it was like kissing your sister. With Romney, it may be more like kissing a mannequin of your sister. Cain is now the third candidate, after Michele Bachmann and Rick Perry, to rise in the polls as a challenger to the perceived front-runner: According to the latest NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll, Cain is actually running ahead of Romney among Republicans, 27 percent to 23 percent. He is also pushing a catchy tax proposal that has won him a lot of attention.

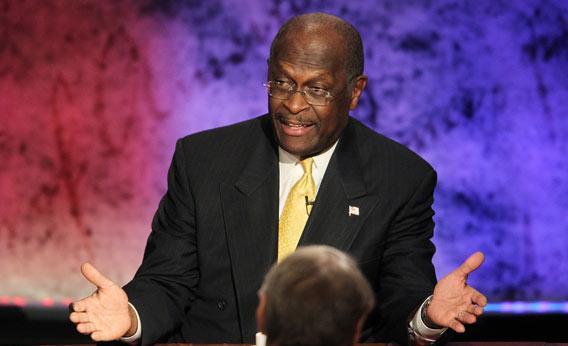

But what really makes Cain different is that he is the most articulate advocate of the Gospel of Simple: the idea that solutions are not as complex as the experts say, and that much of our current mess has been caused by those preaching complexity.

At the last debate Cain took aim at Romney, asking him to name all 59 points in his economic plan. Romney responded that the economic picture was more complicated than that: “Simple answers are always very helpful, but oftentimes inadequate.”Afterward Cain dismissed Romney’s “put down” him, saying “simplicity is genius.” If this sounds familiar, it’s a version of what Ross Perot used to say repeatedly.

This argument for simplicity resonates with Cain supporters like Diane Harris of Naples, Fla., who voted for Cain in a straw poll of conservative activists in Florida last month. “Because Romney is a politician and a bureaucrat he’d say that. Bureaucrats take forever. They never take the simple course to get anything accomplished. He has a big ’ole plan. We’re tired of that. There are common-sense ways to fix stuff but people keep adding more and more levels until it’s an anchor around your neck and you’re in the water.”

A listing of the people who preach complexity would closely resemble the cast of modern villains in politics today: lawyers, career politicians, establishment party bosses, and the media. Complexity is what’s behind Romney’s problem, because it’s code for lack of principle and shifting positions. When Cain supporters and conservatives hear about complexity, they hear loopholes being created. As my colleague David Weigel points out , that’s what’s behind the power of the 9-9-9 plan: fairness. No one can get a lawyer to weasel them a better deal.

In this respect, Cain is not just the non-Romney, he is also the anti-Obama. The president sets marathon records for the length of his answers. This isn’t know-nothingism—Cain’s support in the current Journal poll comes from college-educated voters.

This was the role Perry was supposed to play. It was also Donald Trump’s appeal. But Trump didn’t run, and Perry is still in a tailspin. Cain’s problem may be that he lacks the organization, which in turn may keep him from turning his support into a viable campaign. But this lack of organization is no deterrent to his supporters—in fact, it’s one of his advantages. It’s evidence of his authenticity.

Cain now must find some way to stay in his moment in the spotlight in a way that the other non-Romney candidates have not. His 9-9-9 plan has taken considerable flak from both the left, which thinks it hurts the poor, and the right, where anti-tax advocates like Grover Norquist worry about the sales tax. Cain also might have to answer for his support of the TARP bailout, which rankles the same Tea Party supporters who adore him.

The gospel of simple relies on the same thing hope and change did: the pleasing sound of lines confidently spoken. The downside of this simplicity is that it can be a mask for a candidate who isn’t doing his homework and doesn’t want to bother. That’s what Cain’s advisers who quit his campaign this summer charged: He wasn’t really committed to doing the hard work of running for president. There’s a whiff of this in Cain’s answers to criticism. Responding to a critic of the sales tax portion of his plan Cain told the New Hampshire voter “are you happy with the current tax code? Do we know what’s in it? At least we know what’s in this.” That’s not really a reason. A lot of Cain’s answers lack the crispness of that 1994 debate with Bill Clinton.

In 1996, Forbes was such an unknown that Dole was able to define him and beat him once the voting started. It was a very negative campaign that bled Dole of money. That isn’t likely to be how the Cain and Romney matchup ends. Cain doesn’t have the money. He also endorsed Romney in 2008, which makes it harder to argue he has a disqualifying flaw. Cain has tapped into enthusiasm and is having his moment. Seeing how he turns that into votes is more complicated.