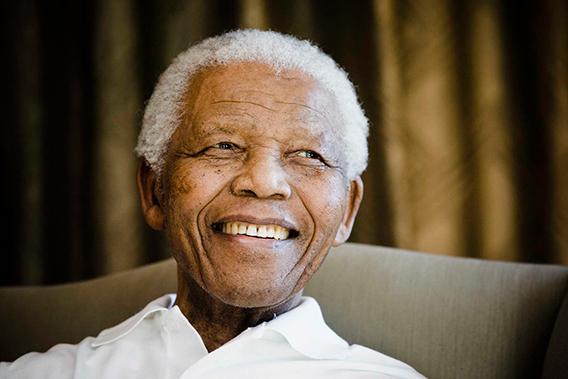

Be in no doubt that Nelson Mandela, the world’s most famous political prisoner, campaigner against racist rule, and magnanimous leader, was a great man. When spending time with him, one felt awed, weak at the knees. Madiba, the tribal name by which he was fondly known by many, had charm and warmth. He was also responsible, more than any other individual, for the remarkably peaceful transition in South Africa.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Madiba’s close friend and fellow leader of the anti-apartheid campaign, once told me how he felt an immense “generosity of spirit” from Mandela. The archbishop naturally saw Christian elements in Madiba’s readiness to forgive his white racist abusers, and his compassion for the weak. “You can even think of Jesus—it’s quite in order to say that there are Christ-like aspects of him.”

But you shouldn’t remember him as a saint. Bishop Tutu didn’t think of him this way—guffawing at the idea that Mandela was anything so dry, hollow, and uninteresting. He may be compared to the likes of Mahatma Gandhi or Mother Teresa, as a great moral figure of our times. But the myth should not overpower the reality of a humane, richly complicated, and passionate individual.

In comparison with other politicians, in Africa and beyond, he stands out for his self-restraint. As free South Africa’s first president, he volunteered for only a single term in office. Look just next door, to Zimbabwe, for a striking contrast: Its near-despotic leader, Robert Mugabe, is now in his fourth, disastrous, decade as ruler.

Yet Madiba is far more interesting than either the villain next door or the simple saintly figure. His achievements are the greater because he himself admitted to errors, at times bungling policy. Those failings matter. He was more likely to learn from mistakes than the haughty sort of leader who refuses to accept he made any. Others should pay as much attention to his slip-ups as to his achievements.

Take the great post-apartheid misery that South Africa suffered in the first two decades of democracy: the AIDS epidemic. Mandela failed as president to tackle the spread of HIV, even as terrifyingly large numbers of South Africans became infected. As early as 1991 he had grasped (judging from one of his private notebooks from that year) that the disease threatened a “crisis for the country.” Yet in office he did almost nothing to stop its spread.

He recalled later at an event I attended in Cape Town that after spending so many years in prison, he was shy when it came to talking about a sexually transmitted virus. South Africa, too, faced a host of other challenges on his watch—political violence, economic upheaval, ongoing racial tension. But his inaction on AIDS then gave way to the outright denial of the epidemic, and harassment of those who tried to tackle the spread of HIV, by his successor as president, Thabo Mbeki. The result was a pandemic that claimed millions of South African lives, many unnecessarily, as drugs to treat victims were long withheld.

To his immense credit, however, Mandela conceded his early error. After leaving the presidency, he became a significant part of a campaign for a new AIDS policy. In retirement, he would speak up for effective education and treatment, especially when his own son succumbed to the disease in 2005. To Mbeki’s fury, too, Madiba pushed within the ruling African National Congress for South Africa to tackle AIDS seriously. With the denialist Mbeki gone from office, thankfully the country has now come to grips with the pandemic.

Or take economic policy. After years in prison, Mandela emerged to lead South Africa still believing, in effect, in Soviet-style economics. It took advice from China’s leaders (among others) to change his mind. But he was willing to switch, to get South Africa’s Afrikaner state-run economy to open up and flourish.

For that, South Africa should be grateful. The past two decades of relative stability and steady economic growth went far better than many predicted would follow the end of apartheid rule. Yet many young, jobless, and angry South Africans are, understandably, still angry. Some attack Mandela as a stooge and a fool for abandoning nationalist, populist, or far-left policies of old.

I recall attending a funeral for a much-loved African nationalist leader in Soweto in 2003, at which both Madiba and Mugabe were present. The crowd of mostly young African men roared in far louder appreciation for the Zimbabwean strongman than for Mandela or any other leader present.

The reason: Many were furious that whites still control a huge proportion of capital in South Africa. Even now some young South Africans accuse Mandela of being a sellout to privileged minority interests. The deal he struck at the end of apartheid, they feel, saw a shift in political power but too little economic change.

I recall one bitter letter to a newspaper a decade ago in which Madiba was called “an albatross round our necks.” Poorer South Africans are the least likely to venerate him. For all the political change that came in 1994, South Africa’s economy is still remarkably dominated by whites.

But Mandela made the best of a very difficult economic job, stabilizing South Africa’s vulnerable post-apartheid economy, encouraging growth, and handing out welfare, even if rapid redistribution of assets between whites and blacks proved impossible to achieve quickly.

His great achievement in policy was, of course, to oversee a profoundly liberal constitution for South Africa that enshrines racial, sexual, gender, and other rights. But also he could compromise, and admit the need to shift policy.

In his personal life, similarly, Mandela had his failings. Take his wife’s word for that. At an event marking Mandela’s 90th birthday, Graca Machel told me of her husband, “He is definitely not a saint!” With great warmth she related, too, how it “definitely wasn’t love at first sight” when the two met in 1990. Their great fondness for each other grew only later.

Even in old age Madiba had an eager eye for beautiful women. One female Irish journalist recalls how he offered to marry her, at a press conference. A close friend of mine, an Indian–South African, thought that Mandela had, in effect, offered to marry her, too (rather more seriously), right before Machel came along. As a young man, a handsome boxer, lawyer of near-regal descent, he was widely described as a heartbreaker.

He could be petty, too. At a small lunch I attended with him in 2005, old friends teased him about his being persnickety and pedantic, after he had demanded a particular brand of sparkling water and rejected another. He insisted that his newspapers and hearing aid be arranged just so. To be fair, he took the gentle mocking in good humor.

His children were known to resent him at times as a distant father. He could be aloof, stiff, and calculating. Machel told me that “Papa” (as she sometimes called her husband) could be stubborn, quick to anger, and intolerant when his grandchildren performed badly at school.

And particularly difficult questions should one day be answered about what he knew of the activities of Winnie Mandela, his second wife and the great love of his life. She, though acquitted in 1991 in one murder case (but convicted of kidnapping), remains under a cloud because of other unexplained deaths in Soweto in the 1980s. There is much yet to be revealed about the disappearances and deaths of political figures in the anti-apartheid movement.

In all this—and in his achievements as a rich, humane, but at times flawed figure—Mandela has much to offer other leaders. He liked to joke about his eventual death, chuckling that the first thing he would do in heaven—he had no doubt that he was headed there—would be to sign up for membership at the local branch of the African National Congress. It was his way of saying that he was a political and pragmatic man: not a saint. Remember him as a warm, powerful, and humane figure. Not an unearthly one.

Watch Nelson Mandela’s 1994 Inaugural Address: