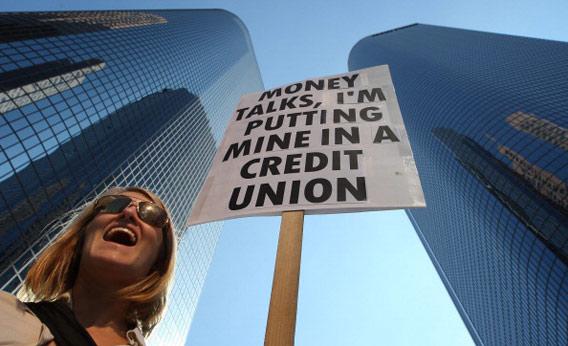

It’s a noble-sounding idea: Pull your money out of one of the big, risk-taking, profit-driven corporate banks whose speculation helped ruin our economy, and put it in a nonprofit, community-minded credit union. No outrageous debit fees. No sneaky other fees inserted insidiously into the fine print. And you’re not just a customer at a credit union, you’re the owner.

Kristen Christian, a 27-year-old Los Angeles art gallery owner, touched off a national movement in October when, fed up with Bank of America in the wake of its announcement that it would charge a $5-per-month debit card fee, she went on Facebook to encourage friends to make the switch to credit unions. They told friends, who told friends. More than 80,000 people RSVP’d to Christian’s “National Bank Transfer Day” Facebook event page, proposing to leave their banks on or by Nov. 5.

I wanted to join the movement. I tried, really. But I couldn’t bring myself to go through with it.

The first problem is that I don’t hate my bank, JPMorgan Chase. In fact, I sort of like it. My first bank account was a Washington Mutual free checking account, back when Washington Mutual was (regionally, at least) famous for free checking. When Chase bought it, its customers were apprehensive. Where I lived, in the San Francisco Bay Area, New York-based Chase embarked on an ad campaign to persuade people like me not to switch. (One billboard along U.S. 101 boasted, “Our ATMs are easy to find—even in this fog.” One problem: The fog is in San Francisco, not sunny San Mateo, where they put the billboard.)

Gaps in its local knowledge aside, Chase made good on its promise to put ATMs all over the place, kept the checking free (at least until earlier this year), and offered spiffed-up online banking services, so I stayed. When I moved to New York, there was no need to change. There’s a Chase ATM in every outlet of Duane Reade, the city’s dominant drugstore chain. The beauty of a national bank.

Still, Christian’s bank transfer campaign has its appeal. You don’t have to be a Guy Fawkes-mask-wearing revolutionary to prefer a locally run co-op to an international megacorporation. But morality and community spirit aside, is it a good deal to join a credit union, now that BofA and other major banks have dropped plans for debit fees?

It depends on what you want from a bank. Because they’re not for profit and don’t pay taxes, credit unions are typically able to offer basic banking services at a lower cost than commercial banks. That means they don’t need to ring up all the checking fees, customer service fees, and overdraft fees that so irk big-bank customers like Christian. Many also offer better interest rates on some savings accounts, often in the form of dividends (since their members are also their shareholders). Service is more personal than at megabanks, and it can be easier for those with subpar credit to get certain types of loans.

On the other hand, credit unions can’t match a lot of the services that big-bank customers take for granted. They typically offer a more limited range of loans and account types. As a rule, they don’t have more than a few branches. ATMs can be scarce. And their online banking services tend to be rudimentary.

On paper, I’m the type of person who could probably get by with a credit union. My balance is embarrassingly small, though usually large enough that I don’t get hit with monthly service fees. I don’t have a car and can’t afford a home. There’s not much I do with my Chase account that I couldn’t do with a credit union. So I thought I would at least explore the possibility of a switch. On the morning of Nov. 5—Christian’s National Bank Transfer Day—I hopped the subway to New York’s Zuccotti Park, home base of the Occupy Wall Street movement. I figured I’d join droves of protesters as they marched, chanting no doubt, into major banks throughout lower Manhattan and demanded that the tellers hand over their dough.

First problem: no droves. Many of the protesters, it turned out, had the foresight to make the switch before the Nov. 5 deadline. Others told me they hadn’t gotten around to it yet. There were a few representatives of local credit unions on hand at the park, passing out pamphlets. I lingered with them for an hour, during which time several passers-by expressed interest in moving their money to credit unions, but none of them actually committed to it. I realized that if I wanted to transfer my money on the day itself, I would be on my own.

That’s when I ran into the second problem: no banks open. A spokesman for the Credit Union National Association, a trade group, had told me that many would open specially on Saturday to accommodate people who wanted to start new accounts. But the big banks apparently didn’t feel compelled to extend the same convenience to those wanting to ditch their accounts. Chase has at least half a dozen branches within a short walk of Zuccotti Park; not one was open.

So I took advantage of Chase’s free “Find an ATM” iPhone app—not the kind of app that many credit unions offer, I suspect—to track down the nearest branch open on Saturdays. It happened to be on Wall Street. But as I neared my destination, shots rang out, crowds roared, and smoke plumed skyward. Startled, I wondered for a moment whether National Bank Transfer Day had turned violent. Rounding a corner onto Wall Street, I found my way blocked by police barricades and saw dozens of SWAT officers milling about in the vicinity of the bank. “What’s going on?” I asked a bystander, who seemed to be taking in the scene with surprising equanimity.

“Shooting a movie,” he said. “Batman.”

Of course. Batman. The bank, needless to say, was closed.

I trudged back to Zuccotti Park, somewhat defeated, but also, I’ll admit, somewhat relieved. When I got there, however, a group had gathered across the street for what several people told me was a big march on the banks. “To take your money out?” I asked hopefully. “No,” a protester responded, giving me a weird look. “It’s Saturday. All the banks are closed.”

The march, it turned out, was in opposition to a proposed settlement between state attorneys general and banks that allegedly engaged in mortgage fraud, “robo-signing” foreclosure documents without properly reviewing them. Who says Occupy Wall Street has no specific demands? One of the organizers of the march, Jessica Stickler, claimed it’s the media, not the protesters, who are uninterested in specific policy proposals. Several news organizations were disappointed to learn Saturday’s demonstration would be about foreclosure settlements and not about closing bank accounts, she said. “I had NBC calling me saying, ‘Please do Bank Transfer Day instead.’ ”

In the end, I didn’t move my money on Nov. 5, but news reports say that thousands of others around the country did. The Credit Union National Association estimates that 650,000 people opened new credit union accounts in the month after Bank of America’s debit fee announcement. That adds up to about $4.5 billion in new savings accounts—a significant chunk of cash, though probably not enough on its own to affect the big banks’ bottom lines.

In fact, it’s possible the transfers could help banks like Chase and BofA, at least in the short term. Hank Israel, a retail bank expert for the management consulting firm Novantas, explained that big banks make most of their money on their wealthiest clients. They actually lose money on some of their basic free-checking customers, especially since new overdraft regulations and the Durbin amendment have limited the fees they can charge.

And while credit unions are welcoming the influx of accounts, they probably won’t see a lot of short-term financial gain either, admits Patrick Keefe, spokesman for the Credit Union National Association. Then again, short-term financial gain isn’t credit unions’ main goal—and that’s exactly why customers are choosing them.