It’s the end of 2016, and I’m gaping at photos of the gargantuan $1.1 billion Spaghetti Junction that has just been completed east of downtown Louisville, Kentucky. This tangle of swooping lanes has a certain undeniable grandeur, but it also represents the worst in American building, the ceaseless, untroubled flow of money into cheap roads. How typical that a highway interchange the size of an Italian hill town, a scar on the downtown waterfront of an American city, is the awe-inspiring project of the day. It could be anywhere, because it’s everywhere.

Consider the following buildings a kind of collective antidote. Each one is an original work of architecture, newly constructed or newly renovated, that doesn’t look quite like anything else we’ve got. And each one has a deep connection to its site, either with a community, an institution, a landscape, or a city. These are landmarks—not just new structures, but signposts by which we’ll know the places we live. A museum, a medical school, a cultural center, a sculpture park, a synagogue, a library, a theater, and an apartment building for billionaires: Here are some of the best things we built in America last year, and why they matter.

Vagelos Education Center at Columbia University Medical Center, New York City

Iwan Baan/Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Iwan Baan/Diller Scofidio + Renfro

An unfortunate tendency of architecture since the invention of the elevator has been to give short shrift to stairs. Ballgown steps of neoclassical buildings like those of the New York Public Library gave way to airless stacks of escalators, like those of the city’s Museum of Modern Art.

And then there’s the Roy and Diana Vagelos Education Center at Columbia University Medical Center. The architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, drape the 14-story tower’s classrooms and social spaces around its staircase, which they call the “Study Cascade.” Concrete supports burst through the curtain wall, projecting the switchbacks to passers-by, like a hiking trail snaking up a glass mountain. (It’s beautiful on the inside, too.)

Central Library, Boston

© Bruce T. Martin

© Robert Benson Photography

In a downtown stuffed with unloved modern buildings, the 1972 Johnson wing of the Boston Public Library always stood out. Unlike the nearby Boston City Hall, it never got much love from fellow architects. Its mastermind, Philip Johnson, himself admitted it didn’t quite turn out right. “Hulking, barren, and closed off from the street by a barricade of 97 vertical granite slabs, or plinths,” wrote Renée Loth in the Globe three years ago, “the unwelcoming façade of the Johnson wing today mocks the spirit of the library’s inscribed motto, ‘Free to All.’ ”

A $78 million renovation by William Rawn Associates, completed this year, preserves Johnson’s sense of monumentality and corrects his mistakes. For example, the modernist giant didn’t want to build windows. Trustees (and one assumes, readers) wanted natural light. The result was a compromise that Cliff Gayley, a principal at the firm, described as windows tinted like a state trooper’s sunglasses.

The renovation—along with that of New York’s Met Breuer, which also reopened this year—reminds us that midcentury architecture can be tastefully updated, preserved, and reimagined. For Bostonians, it’s simpler. “The psychological effect of this de-fortification is dramatic,” writes Dan Adams in the Globe. “By bringing the sidewalk flush with a long facade of clear, two-story windows, the architects have made the building—and even the institution it houses—seem infinitely more approachable.”

432 Park Avenue, New York City

Eric Kilby/Flickr CC

Most of the buildings here are public or open to visitors, because what good is good architecture if it’s inaccessible? 432 Park Avenue, designed by the Uruguayan architect Rafael Viñoly, is an outlier. It’s one of the most private buildings in the world, in the sense that neither you nor I nor anyone we know will ever wind up inside it, unless we’re delivering the mail. It’s also an unavoidable presence on the New York skyline, hovering over our heads wherever we are like a glitch in a video game sky.

This building reportedly contains more residential wealth than the entire city of Hartford, Connecticut. But as I argued in the Village Voice earlier this year, it is a more honest symbol of the world today than Northern California’s fenced-off palaces or London’s double-wide townhomes. As a building, it is shockingly slender and tall, proof of human ingenuity against the wind and evidence of good taste against the neighboring supertall towers further west.

Temple Emanu-El, Dallas

James F. Wilson/Cunningham Architects

James F. Wilson/Cunningham Architects

There has never been a strong tradition in synagogue architecture, which is exciting for peripatetic Jews with an interest in history and design: Temples often mirror the style of their time and place, and absorb its preoccupations. That’s the idea behind the Stern Chapel, the centerpiece of the Dallas architect Gary Cunningham’s $34 million renovation to Temple Emanu-El, a midcentury synagogue in North Dallas that’s home to the largest reform Jewish congregation in the Southwest. One of the walls of the bright wood room, which seats 450, is made of glass panels and looks out on a courtyard of live oaks. “What we wanted to do is bring the beauty of nature into the worship experience,” chief rabbi David Stern told Mark Lamster, the architecture critic at the Dallas Morning News.

The chapel is a complement to the synagogue’s midcentury spaces, including the Olan Sanctuary, a rounded room lit by hanging lamps and stained glass. Those have been painstakingly restored. The congregation has moved three times since its first temple was built in 1876, in the process shuffling between buildings of Moorish, Romanesque, and neoclassical styles. This time, it opted instead to refurbish and expand its modernist campus, nestling the congregation’s future in the architecture of its past.

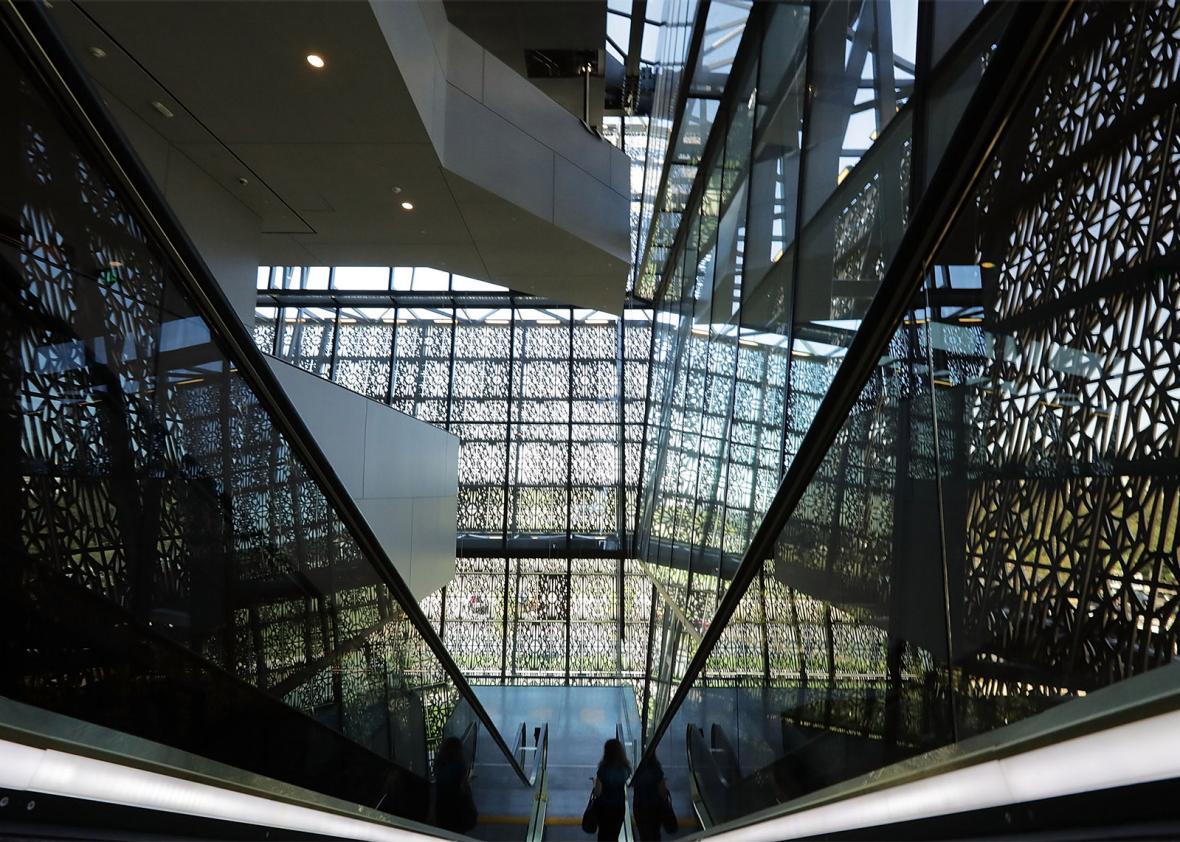

National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

No American building was more scrutinized and celebrated this year than the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the latest and final grand addition to the National Mall. Design architect David Adjaye has said its tiered profile, three top-heavy trapezoids of bronze lattice, is modeled after a Yoruba design. That façade, tapering downward, makes the building feel sturdy next to the flighty Washington Monument. The inside—which includes a vast underground hall—is nevertheless full of grand, open spaces.

One of the best parts about going to the Blacksonian, as Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris nicknamed it in their New York Times podcast, is observing the diverse and profound effects it has on other visitors. This is partly thanks to the powerful symbolism of a black museum on the mall; it is partly due to the wrenching emotional narrative of the exhibits. But it is also a tribute to the architecture, which imparts to a long visit moments of elation and grace.

Tippet Rise Art Center, Montana

Iwan Baan

Andre Costantini

On the treeless hills of southern Montana, just north of Yellowstone National Park, is the latest contribution to the culture of land art in the American West. It’s not one building, like the others featured here, but it is a new kind of place. Tippet Rise Art Center is, in short, the world’s largest sculpture park—but it’s also a concert hall, a working ranch, and a wilderness. Think of New York’s Storm King, only 500 miles from the nearest large city and 20 times the size.

The park is the creation of the artists and philanthropists Peter and Cathy Halstead, and it is designed, like Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field, to be in some ways a solitary experience, with a limit on wandering tourists of 100 a day (plus 3,000 sheep and 500 cattle). But there is also a barnlike concert hall, designed by Laura Viklund of Gunnstock Timber Frames, which seats 150 for performances of works like Hamlet and Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

The sculptures, Rachel Syme wrote in Surface, “don’t compete with the land, they give into it.” Even the works of Mark di Suvero, whose giant amalgamations of painted steel have loomed over passers-by in downtown Chicago and Milwaukee, among other American cities, are dwarfed by the landscape. His sculpture Proverb, Syme writes, “formidable in Dallas, looks almost fragile here, like it will one day turn to dust.”

Faena Forum, Miami

Iwan Baan

Philippe Ruault

Bear with me when I tell you that the Argentine entrepreneurs behind Faena Forum, a suite of three buildings in Miami Beach, call it an “alchemical collaborator” and a “polyphonic space.” In simple terms, it’s an unprogrammed collection of rooms open to events, exhibitions, lectures, and performances. Emphasis on “unprogrammed”: This is the kind of freeform cultural center you’d typically associate with a bootstrapped warehouse in Miami’s hip Wynwood Art District.

Only it’s a brand-new, matte-white cylinder-meets-cube of 43,000 square feet, designed by Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture for the high-strung cityscape of Miami Beach. The façade is patterned like the shadow of a palm tree, producing 350 different-shaped windows. The building also features a pink marble amphitheater and a 40-foot dome in which, Andres Viglucci writes in the Miami Herald, “a spiraling ramp around its perimeter wall leads up to an observation balcony high above the floor and a ceiling that, unlike the coffered Pantheon, has corkscrewing supports reminiscent of the inside of the shell of a chambered nautilus.” Enthusiasts of garage architecture will also appreciate the perforated walls, like coral, or a cheese grater, of the six-story car park next door.

Does it sometimes feel like there’s little regional pedigree to American architecture? Faena Forum will set you straight. This could exist nowhere but Miami.

Blue Barn Theatre, Omaha, Nebraska

Paul Crosby/Min Day

Paul Crosby/Min Day

The Blue Barn Theatre building was completed in 2015, but because its first year of performances took place largely in 2016, I’m including it here anyway. The smallest project on this list by far, the rebar-clad building asserts the creativity and liberty that a small arts organization can have in a city like Omaha, Nebraska—and by extension, testifies to the cultural vitality of the country’s smaller cities.

The new home of Blue Barn was designed by the architects E.B. Min and Jeffrey Day, but it features a long list of local and far-flung collaborators. The maple floor of the lobby came from a nearby teardown; other wood fixtures come from trees the city has recently felled. Bathroom sinks sit on South Dakota granite reclaimed from the façade of a steakhouse that formerly occupied the site. The seating is a hand-me-down from another local theater. The designers collaborated with four artists on the building’s structural elements, including a vestibule of mottled Nebraska-made bricks and a giant backstage door that serves to open the theater up to a hilly back lawn. Try doing that in the East Village.

In lesser hands, that might add up to a distracting collage, but in Min’s and Day’s, the result is both dazzling and cohesive.

Turkey award: Trump International Hotel and Tower, Washington, D.C.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

I’d be remiss if I didn’t include the 2016 project that most epitomizes the year: the garish renovation of the Old Post Office Pavilion that has yielded Donald Trump’s latest business venture.

Back in October, when the Trump campaign was in full meltdown mode following the release of the Access Hollywood tapes, I visited and took in the overcooked opulence of its lobby, a grand courtyard space festooned in Trump style, which is to say, at once gaudy and goofy. “Like Trump’s vile groping boasts,” I wrote, “it’s a reminder that he is still, entering his eighth decade, a desperately insecure striver who has never stopped trying to prove himself to be rich, powerful, and sexually potent—and never succeeded.”

Well, scratch out the “powerful” on that list of failures—and maybe the “rich,” too. There is no clearer symbol of the Trumps’ transparent desire to use the presidency to enrich themselves than this hotel, which he should be contractually obligated to abandon come Jan. 20—but won’t. It’s a better monument to 2016 than I knew.

* * *

Honorable mentions from abroad: London’s Tate Modern Switch House, by Herzog and de Meuron; Antwerp, Belgium’s Port House, by Zaha Hadid; the National Taichung Theater in Taiwan, by Toyo Ito; and the Palestinian Museum in Ramallah, by Heneghan Peng.*

*Correction, Dec. 30, 2016: Due to a production error, this article originally misidentified the location of Antwerp. It’s in Belgium, not the Netherlands.