This is the second of three articles excerpted from Richard Ford’s new book, Rights Gone Wrong: How Law Corrupts the Struggle for Equality.

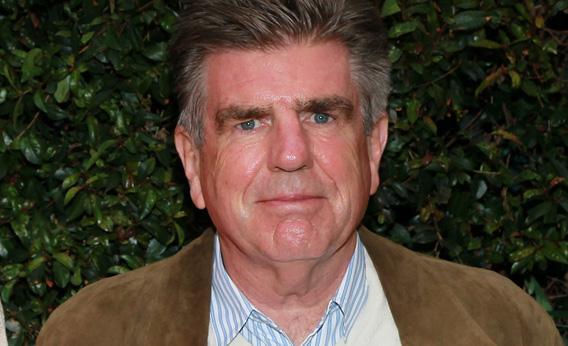

Tom Freston, who helped start MTV and was present at the creation of such timeless classics as Beavis and Butthead, earned a nice living as an entertainment executive. When he retired as head of Viacom in 2006, he received a $60 million severance package. So why, in the late 1990s, did he sue the city of New York to reimburse him for his son’s private-school tuition?

In 1995, after his son was diagnosed with ADHD, Freston enrolled him in the prestigious Stephen Gaynor School, which specializes in students with learning disabilities. Under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, if a school district receives federal funding, it must develop “specially designed instruction, at no cost to parents, to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability.” If the school district fails to provide a child with an “appropriate” education, the parents are legally entitled to tuition reimbursement for private schools.

New York agreed to compensate Freston in 1997 and 1998. In 1999 (annual tuition: $21,819), it offered Freston’s son a slot at a prestigious public school for students with disabilities. Freston declined. The district then declined to reimburse him. Freston then sued. For him, the case wasn’t about money—he donated his reimbursements to a tutoring program for public school children—but about the principle: He was fighting for the rights of all students with disabilities. From the district’s perspective, the case was about an abuse of the law by wealthy parents “who never intended to use the public schools.”

They both have a point. What the case shows most starkly, however, is the inadequacy of using civil rights law to improve the education of all students—both with and without disabilities.

One of the briefs filed on behalf of the city of New York complained that “[I]n one recent year, public schools spent over 20% of their general operating budgets on special education students. But, as a brief filed on behalf of Freston pointed out, most of that amount was spent on special education in public schools—not on tuition reimbursement. Tuition reimbursement wasn’t a unique problem—it was just a dramatic example of the cost of special education generally.

Mark Kelman, my colleague at Stanford Law School, and Gillian Lester, now a professor at U.C.–Berkeley Law School, conducted an extensive study of learning disability claims in public schools and wrote a book about it. They visited a number of local school districts and talked to local school administrators, teachers, and parents to see how the disability rights laws worked in practice. Their conclusion: Treating the education of learning disabled children as a civil rights issue benefits rich families at the expense of the poor, and actually makes it harder to educate most students—disabled and nondisabled alike.

For nondisabled children, the problem is obvious: The law requires school districts to spend more—often a lot more—on costly special services reserved exclusively for children diagnosed with learning disabilities. This might make sense if the districts were awash in money, or if the special services were uniquely helpful to the children with learning disabilities, the way, say, Braille texts are uniquely helpful to the blind. But in fact, many of the special services the schools are required to provide for children with learning disabilities would benefit any child: smaller classes with better student- teacher ratios, one-on-one tutoring, immunity from discipline for disruptive behavior, extra time on exams.

Under IDEA, schools that fail to effectively educate disabled children can be made to pay for private school tuition. But the public schools—especially those in large cities like New York—are failing to educate many of their students who aren’t disabled, too. In 2004, more than 3 percent of all students served by the District of Columbia schools were in private placements, at a cost of 15 percent of the district’s entire budget. Yet D.C. schools “struggle to provide an adequate education to any of their students,” write two researchers at the Manhattan Institute. “Disabled students are entitled … to demand an adequate education,” they note, while nondisabled students “lack the same mechanism for exiting failing schools.”

It’s easy for parents to argue that public school classes don’t offer an adequate education to their learning disabled children when they don’t offer an adequate education to anyone. Contrary to the civil rights theory underlying the IDEA, disabled students who don’t receive an appropriate education aren’t necessarily being discriminated against—tragically, they’re often receiving the same (poor) quality education as everyone else.

The civil rights approach to special education also disserves many disabled children—especially those from poor and minority families. Special education under the IDEA can range from a reimbursement of expensive private school tuition to isolation in a dead-end class with “slow” children. Kelman and Lester worry that poor children typically receive very different treatment under IDEA mandates than do the children of wealthy parents, who have the wherewithal to pressure school districts for better and more costly options: “The IDEA system,” they write, “permit[s] relatively privileged white pupils to capture high-cost … in-class resources that others with similar educational deficits cannot obtain, while, at the same time, allowing disproportionate numbers of African-American and poor pupils to be shunted into [special ed] classes.”

There was even more reason to worry that the IDEA system benefited the rich at the expense of the poor in the case of demands for tuition reimbursement like Tom Freston’s, because only wealthy parents could afford to send their child to an expensive private school and sue for reimbursement later.

In 2009 students with learning disabilities accounted for almost half the entire population of disabled students receiving special services under the IDEA.

It’s no accident that the explosion of learning disability diagnoses comes at the same time the public schools are increasingly troubled by overcrowding, spotty teaching quality and violence. Given the state of many American public schools, who can blame parents for seeking private alternatives or trying to finagle extra resources for their children? While all students suffer from overcrowding and indifferent teaching, poor performers—whether diagnosed with disabilities or not—suffer most.

The parents of such students are right to insist that the schools are failing to help their children realize their potential, and failing them more dramatically than they are failing students who learn easily and without much help. In that sense poor schools are inherently discriminatory: They make any student who has difficultly learning—for whatever reason—worse off than students who learn easily.

The solution is obvious: better services for everyone. But IDEA doesn’t make the public schools better. Instead it shifts resources to a small fraction of the larger group of people who need them most. This might make some sense if that small fraction were especially injured by inadequate education, or if these students would uniquely profit from the extra resources. But if, as many educators believe, these children need the same things that any other student needs—good teaching in small classes—then it’s wrong to treat their needs as inalienable civil rights when we treat the needs of other students as luxuries that nearly bankrupt districts can’t afford.

At any rate, the IDEA doesn’t even try to find out whether children with learning disabilities get more out of extra resources than other children would. The law is premised on the unexamined conviction that some children should have more than others—regardless of whether they need it more, or will benefit more from it. All in the name of equality.