This is the first of three articles excerpted from Richard Ford’s new book, Rights Gone Wrong: How Law Corrupts the Struggle for Equality.

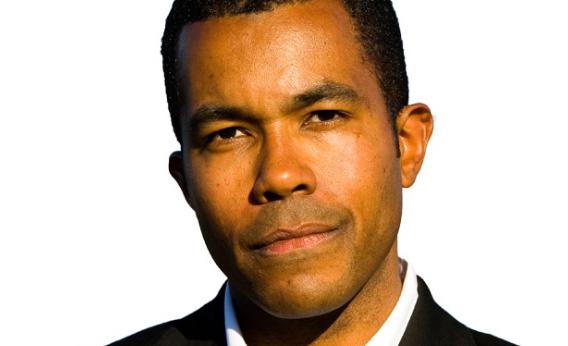

Courtesy of Richard T. Ford.

On May 4, 2006, a man named Michael Cohn filed suit to stop Mother’s Day. The previous year, the California Angels had held a Mother’s Day celebration, which included a “#1 Angels Baseball Mom” contest and a Mother’s Day tote bag giveaway. According to the court that heard Cohn’s lawsuit, “due to the difficult logistics of discerning which women were mothers in the heavy traffic of entry to the game, the team decided to generalize ‘mothers’ as females 18 years and over” and give them—and only them—the Mother’s Day gifts. Cohn didn’t fit that description, and so he didn’t get a fetching Mother’s Day goodie bag. Enraged that he was denied a gift because of his sex, he sued.

Rest easy: The courts dismissed the lawsuit, and the Golden State remains safe for maternal celebrations. The California Court of Appeals pointed out that the Angels did not in fact intend to denigrate or disadvantage men; instead the team wanted, as Scripture admonishes and as loving children have done for millennia, to honor their mothers: “The intended discrimination,” the court insisted, “is not female versus male, but rather mothers versus the rest of the population.” The court further noted: “It is a biological fact that only women can be mothers. … [T]he Angels did not arbitrarily create this difference.”

In other words, it was not the Angels’ Mother’s Day celebration that discriminated against Michael Cohn. It was Mother Nature, and her policies are not subject to the court’s jurisdiction.

So far, Mother’s Day has survived legal challenge. But the zealous guardians of sexual equality have had success in other struggles against the menace of matriarchy, in particular the social and cultural scourge that is “Ladies’ Night.” In 1979, a student named Dennis Koire saw the ugly face of discrimination when he was excluded from a bar that admitted his female companion. Koire soon began to notice female chauvinism everywhere: Car washes offered women discounts on discriminatory “Ladies’ Days” and nightclubs waived cover charges for women. When Koire sought to assert his equal rights, not only was he rebuffed—he was ridiculed. “Come back when you’re wearing a skirt,” quipped one car wash manger. “So sue me,” dared a nightclub proprietor.

Koire did just that: With the help of the ACLU he took his complaint all the way to the California Supreme Court, which in 1985 held that “Ladies’ Nights” violated the state’s Unruh Civil Rights Act, which in dramatic and unequivocal language entitles anyone in the state to “full and equal accommodations, advantages, facilities, privileges, or services in all business establishments of every kind whatsoever.”

Koire’s lawsuit was the beginning of the end for ladies’ nights in America. In 1998 David Gillespie filed a complaint with the New Jersey Division of Civil Rights against the Coastline Restaurant, which waived a $5 admission charge and offered drink discounts exclusively to women on ladies’ night. The state sided with Gillespie in 2004 and dropped the gavel on ladies’ nights. In 2006 Stephen Horner sued a Denver nightclub over its ladies’ night policy. Horner explained his opposition to the unfair advantages women enjoy in American society: “Women are growing up these days feeling they’re entitled to favors. I believe this entitlement mentality is counterproductive to the social goals of a[n] egalitarian society.” He then added, apparently without irony: “I’m going to ask for every dollar I’m owed to the letter of the law, which is $500.”

In 2007 Todd Phillips, a lawyer specializing in gender bias, sued a Las Vegas gym that offered women a discount on initiation fees and a separate workout area. Courts in Iowa, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Hawaii have found that ladies’ nights and similar promotions or discounts are unlawful sex discrimination. And in 2007, the California Supreme Court reaffirmed its opposition to ladies’ nights, finding for lawyer Marc Angelucci of the National Coalition of Free Men—not a gang of Chicago-school libertarians but a “men’s rights” organization—in his lawsuit against a Southern California club that occasionally waived its $20 entrance fee to women. Angelucci was awarded $4,000 in damages for each violation.

Photograph by Jupiterimages/Thinkstock.

Although the law in several states apparently prohibits ladies’ nights, popular opinion echoes the approval of Kool and the Gang: It’s ladies’ night, and the feeling’s right. After New Jersey banned ladies’ nights in 2004, then-Gov. James McGreevey condemned the decision as ”bureaucratic nonsense” that “reflects a complete lack of common sense and good judgment.” (Attempts to amend New Jersey’s civil rights laws to allow ladies’ nights failed.*) A columnist in the National Review called the ruling “emblematic of the growing arrogance of a government caste that seeks to micromanage every aspect of American’s lives.” Liberals, meanwhile, complained that the decision distorted the true purpose of civil rights laws and diverted resources from real injustices. The less politically minded lamented the death of chivalry and a misguided step toward an androgynous culture.

In the Koire case in California in 1985, California Supreme Court Chief Justice Rose Bird insisted that “the legality of sex-based price discounts cannot depend on subjective value judgments about which types of sex-based distinctions are important or harmful.” On the legal Web site Findlaw, a lawyer compared ladies’ night to the racist contempt of apartheid and the Jim Crow era, insisting that “one act of discrimination does not cancel out another. … If a bar had a ‘Whites’ Night’ followed by a ‘Blacks’ Night’ no one would blink an eye before denouncing … each night.” George Washington University law professor John Banzhaf, who has encouraged his students to sue to stop ladies’ nights, argues that ladies’ night is in principle indistinguishable from discriminatory customs that denigrate women—that discrimination is discrimination. Using this kind of logic, offering your seat on the bus to a woman because of her sex is just as bad as making black people sit in the back of the bus because of their race.

Today most people agree that sexist rules and customs that keep women down and perpetuate stereotypes of female frailty, passivity, and incompetence should be prohibited in the workplace and expunged from the public sphere. But only a handful of extremists would extend laws against sex discrimination to forbid chivalry or ban a time-honored tradition like Mother’s Day or an innocent custom like ladies’ night.

Of course, read literally, without the mediating influence of good judgment or common sense, the laws that prohibit truly demeaning and invidious sex discrimination apply to ladies’ night promotions and the use of female sex as an expedient proxy for mothers in a Mother’s Day giveaway. Rights go wrong when propelled beyond the boundaries of good sense by abstract thinking. Justice Bird’s admonishment notwithstanding, legal prohibition must depend on judgments about which practices are important or harmful. Not every distinction—even if based on race or sex—is invidious.

Correction, Nov. 2, 2011: This article originally stated that New Jersey had amended its civil rights laws to allow Ladies’ Nights. It has not. (Return to the corrected sentence.)