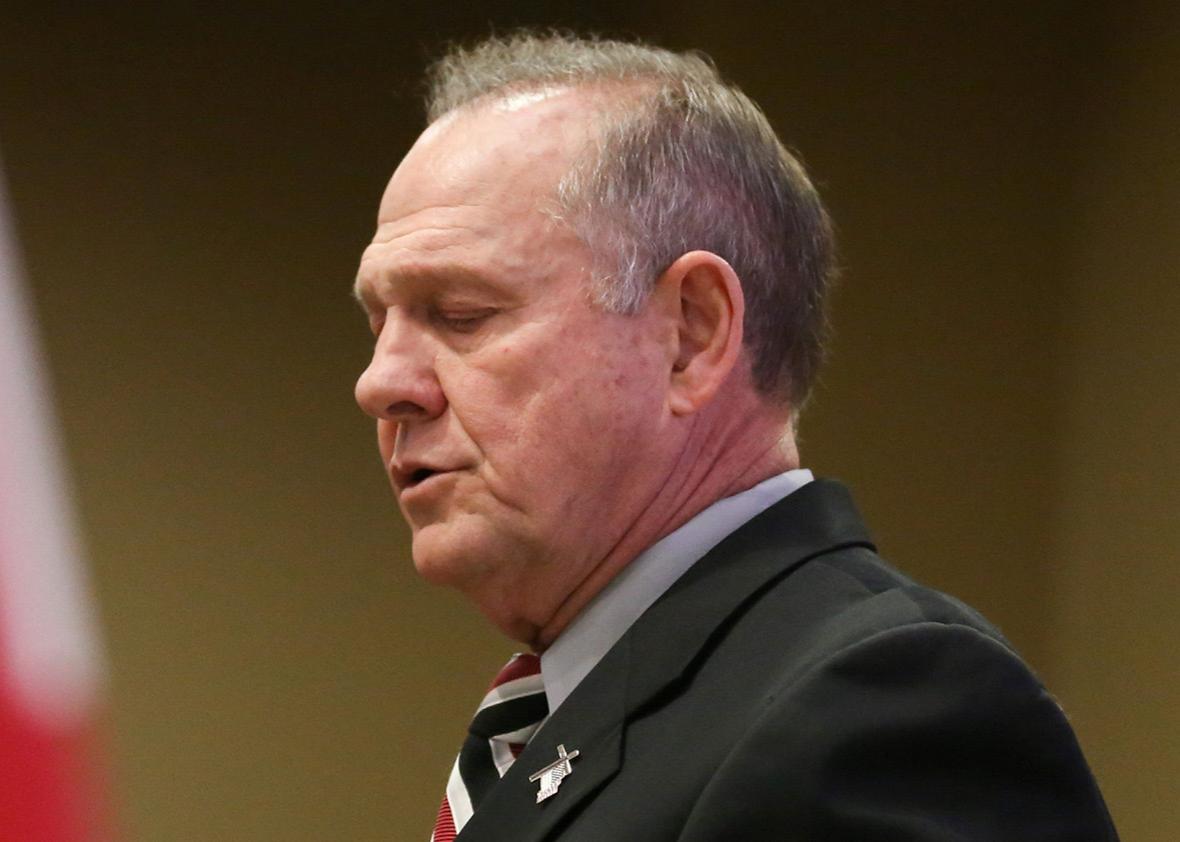

Alabama Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore has made a career out of disparaging minorities, violating federal court orders, and promoting fringe conspiracy theories. He was plainly unqualified for the U.S. Senate before the Washington Post reported, in a thoroughly sourced and corroborated story, that he allegedly molested a 14-year-old girl as an assistant district attorney, and before yet another woman came forward to allege Moore groped and assaulted her when she was 16.

These revelations have spurred a new line of attack against Moore among progressives: that as the chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, he cast the sole vote in favor of a 17-year-old convicted of raping a 4-year-old. This criticism is misleading, unjust, and dangerous. The implication that Moore favored the defendant because of the judge’s own alleged history of molestation is especially absurd. Moore’s dissent was perfectly plausible, and his broader argument would still permit Alabama to imprison the rapist for years. Liberals have long criticized those who attack judges for ruling in favor of criminal defendants when the law compels them to do so. They should not adopt the strategy they have long decried because Moore himself is a monster.

Higdon v. Alabama, the case in question, presented a straightforward question of statutory analysis. Eric Lemont Higdon, a 17-year-old day care worker, was charged with sexually assaulting a 4-year-old. A jury convicted him of first-degree sodomy, which the state defines as “deviate sexual intercourse” by a person age 16 or older with “a person who is less than 12 years old.” The jury also convicted Higdon of first-degree sodomy by forcible compulsion. Higdon appealed, and the Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the first charge while throwing out the second. He appealed once again, and the Alabama Supreme Court reversed the lower court by an 8–1 vote.

Moore dissented. He acknowledged that Higdon had committed first-degree sodomy but argued that his crime, while “abhorrent,” did not qualify as sodomy “by forcible compulsion.” In everyday English, Higdon undoubtedly engaged in “forcible compulsion,” as would any child rapist. But under Alabama law, Moore noted, the term has a specific meaning. The Alabama legislature defines “forcible compulsion” as “[p]hysical force that overcomes earnest resistance or a threat, express or implied, that places another person in fear of immediate death or serious physical injury to himself or another person.”

The majority concluded that the threat of sexual assault alone qualified as an “implied threat” under this statute. Once again, in plain English, that would certainly make sense. But the Alabama statute expressly defines an “implied threat” as something more: an action or statement that places the victim “in fear of immediate death or serious physical injury.” And in Higdon, no such act was proved to the jury. In a previous case, the Alabama Supreme Court had decided that when an adult rapes a child with whom he is “in a relationship of trust,” such a threat is inherently present. Now the court extended that rule to any situation in which a legal juvenile sexually assaults another minor.

This extension of precedent, Moore wrote, “may be a noble cause,” but it is also “policymaking” and therefore “beyond the role of this Court.” He argued that it also opened the door to strange applications of the statute. Under the majority’s new rule, “a 10-year-old could be convicted of ‘first-degree sodomy by forcible compulsion’ for intercourse with an 8-year-old, or a 6-year-old with a 4-year-old, or a 16-year-old with a 14-year-old.” The Alabama legislature may criminalize this conduct, Moore wrote, but it did not do so through this statute.

Moore’s dissent isn’t just defensible. It is actually fairly persuasive, at least from a textualist standpoint. (The late Justice Antonin Scalia, who believed judges must interpret ambiguous criminal statutes in favor of the defendant, would probably sign onto it.) To be sure, the Alabama law is terrible: It uses the archaic classification of sodomy (which is unconstitutional when applied to consenting adults) and does not recognize the heightened vulnerability of children. But, as Moore wrote, the court had “no right or authority to make a new law”—only to interpret the one on the books. And strictly construed, Alabama’s definition of “first-degree sodomy by forcible compulsion” does not apply to Higdon’s crime.

There is also truth to Moore’s accusation that the majority engaged in policy-making. For most of American history, few states had defined child sex crimes outside of statutory rape. In the mid-20th century, state legislatures decided to create a more comprehensive legal regime concerning child sexual abuse. Some crafted an entirely new set of crimes focusing on unique aspects of the child victim. Others, including Alabama, simply copied existing crimes but applied them to children. University of Kansas Law professor Corey Rayburn Yung told me that this shortcut “led to some strange oversights,” most notably with regard to the question of force.

“Force with a child is arguably different than force with an adult because of size, power, and maturity,” Yung said, but Alabama law does not reflect this commonsense distinction. So the state Supreme Court chose to fix the problem by effectively redefining force in cases of child sexual abuse. That may be an honorable undertaking. But there is nothing dishonorable about Moore’s insistence that the legislature fix its own mistakes.

During the Senate primary, Moore’s opponent Luther Strange ran an ad attacking him for his Higdon dissent, implying that Moore wanted to spring a child rapist from prison. In fact, Moore agreed that Higdon’s conviction for first-degree sodomy could stand, ensuring he would spend years in prison. His Democratic opponent, Doug Jones, has not yet brought up the dissent.

He shouldn’t. Republicans have long attacked judges who rule in favor of criminal defendants as “soft on crime,” a deeply disingenuous charge that subverts the Constitution’s presumption of innocence. Richard Nixon ascended to the presidency on a platform that castigated the Supreme Court for safeguarding the rights of criminal defendants. So did his Republican successors; Ronald Reagan even denounced judges for properly applying the Fourth Amendment to criminals. The trend continues to this day. In 2016, a right-wing group launched a smear campaign against potential Supreme Court nominee Jane Kelly for representing a child molester as a public defender—suggesting that, as a judge, she would be soft on pedophiles. (Republicans also put out an ad lambasting Hillary Clinton for defending an accused child rapist.)

This tactic is particularly egregious when used against elected judges. Data show that elected state supreme court justices become increasingly less likely to rule in favor of criminal defendants the more frequently television ads air during a judicial election. Elected judges also hand out harsher sentences, and more capital sentences, when a judicial election is looming. The widespread attacks on judges as “soft on crime” have concrete and highly prejudicial consequences for the criminal justice system. At the very least, these attacks scare many judges into bending the law in order to send as many defendants to prison for as long as possible.

Progressives contribute to this problem by condemning Moore for his Higdon dissent, reinforcing the false notion that a decision in favor of a despicable defendant is, itself, despicable. Even worse, liberals who tie Moore’s Higdon dissent to his own alleged misconduct suggest that judges may be projecting their own crimes upon certain defendants—a ridiculous logical leap that would turn many judges into secret murderers. There are plenty of legitimate reasons to castigate Moore. He is unfit to serve as a judge, and he is unfit to occupy political office. His Higdon dissent is not the reason why.