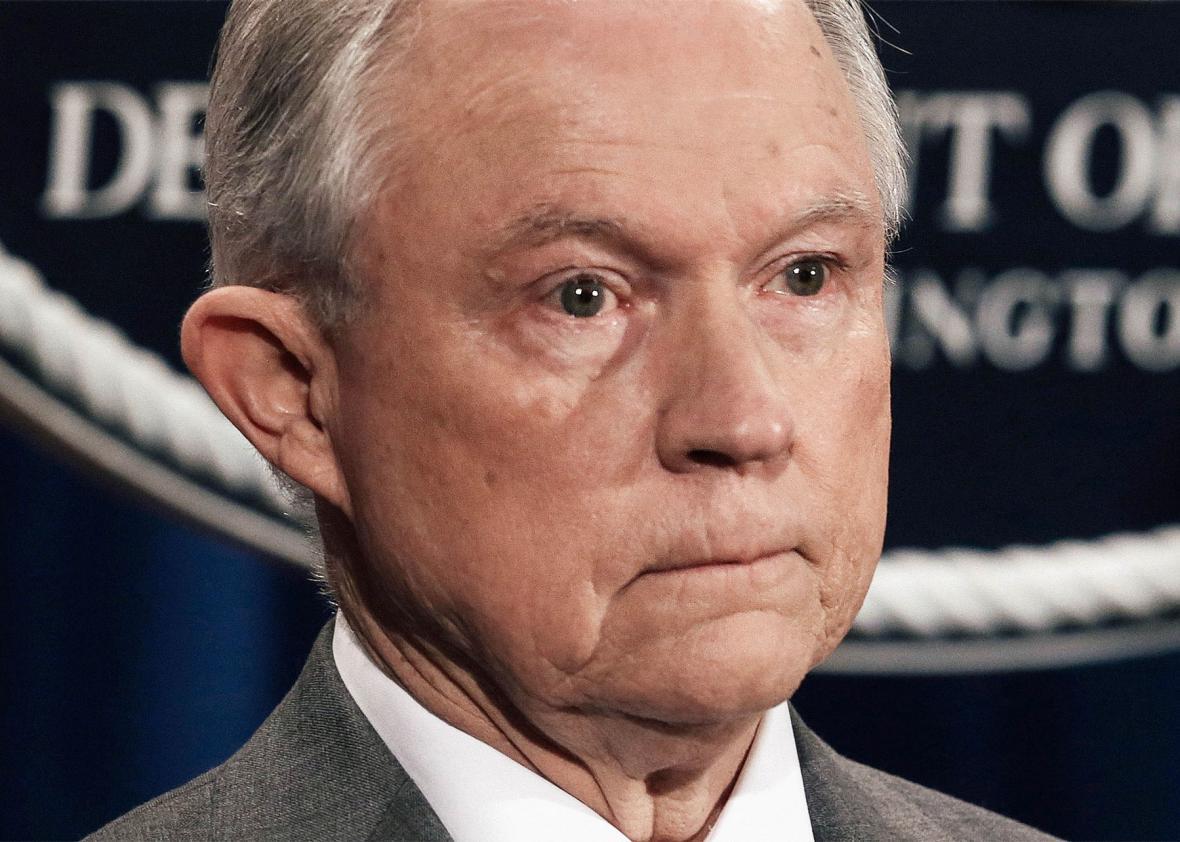

Under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the Department of Justice has switched sides in several key court battles, reversing positions the agency took during the Obama era. Already, the DOJ has withdrawn its opposition to Texas’ draconian voter ID law and to mandatory arbitration agreements designed to thwart class actions. Now the agency has made another about-face: On Monday, it dropped its objections to Ohio’s voter purge procedures, which kick voters off the rolls for skipping elections. The DOJ is now arguing that such maneuvers are perfectly legal.

Ohio’s voter purges are at issue in a Supreme Court case, Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, which the justices will hear next term. The state purges voters from the rolls relentlessly, removing around 2 million people between 2011 and 2016—with voters in Democratic-leaning neighborhoods twice as likely to be purged as those in Republican-leaning neighborhoods. While most states regularly clean up their voter rolls, Ohio is unusually aggressive in targeting individuals because they have not recently cast a ballot. Up to 1.2 million of those 2 million purged voters may have been removed for infrequent voting.

There’s a problem here: Federal law prohibits states from purging voters for casting ballots irregularly. The National Voter Registration Act of 1993 declares that voter-roll upkeep “shall not result in the removal of the name of any person from the official list of voters registered to vote in an election for Federal office by reason of the person’s failure to vote.” Civil rights groups sued Ohio on behalf of purged voters, and shortly before the 2016 election, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the state’s purging procedures violated the NVRA. At least 7,500 additional Ohioans were able to cast ballots because of the court’s decision.

In the lower courts, the Justice Department sided against Ohio, asserting that the state’s purges ran afoul of the NVRA. The agency’s reasoning was simple: Unlike most states, Ohio targets voters for removal when they do not cast a ballot for two years. It sends these individuals a confirmation notice demanding they confirm or update their addresses. If a voter does not respond to the notice and does not vote in the next four years, her registration is cancelled.

The issue here is that the NVRA does not allow states to start the purging process simply because a voter hasn’t cast a ballot in some period of time. Instead, the NVRA requires some initial indication that a voter has moved before the removal process can begin. The statute itself gives one example: “change-of-address information supplied by the Postal Service.” In guidance issued in 2010, the Justice Department provided others, including election materials that are returned nondeliverable.

The 6th Circuit agreed that Ohio could not commence the removal of a voter from the rolls in the absence of reliable evidence that he has moved. Ohio appealed, and in May the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. In a brief filed with the court on Monday, the Justice Department announced that after “the change in administrations, the department reconsidered this question” and decided that “the NVRA does not prohibit a state from using nonvoting” as the basis of removal from the voters rolls. Put differently, the DOJ thinks that states can purge voters without any real evidence that they’ve moved. If an Ohioan misses a few elections and doesn’t answer one letter, she can be removed from the rolls without her knowledge.

No career attorneys from the Civil Rights Division signed the brief, presumably indicating their resistance to the agency’s new stance. Career attorneys also refused to sign onto recent DOJ briefs opposing gay rights and supporting Texas’ voter ID law; it also appears that they will not be involved with the agency’s campaign against affirmative action. The agency’s political appointees are leading its political fights.

In the end, the Justice Department doesn’t get to decide what the NVRA means. That task falls to the Supreme Court, which will render a decision next term. But the DOJ’s sudden change of heart does provide further evidence that the Trump administration has set the NVRA in its crosshairs. We already know, for instance, that Trump’s voter fraud commission is designed to provide cover for Congress to gut the law, and that the commission will try to use inflated claims of fraud to coerce states into purging their rolls.

Monday’s brief confirms that the DOJ is also keen to attack the NVRA. In June, the agency sent an ominous letter to 44 states suggesting that the NVRA requires them to purge their voter rolls more vigorously. Now it has reinterpreted that law to make such purges easier. The department’s political appointees are transforming the NVRA into a disenfranchisement device. If the courts take their side, a crowning achievement of the voting rights movement could become a tool of voter suppression.