Last year, a police officer in New Mexico arrested an acquaintance of his own supervisor and reported another officer’s misconduct. In 2014, a city plumber and rental housing inspector in Illinois complained about his city’s failure to enforce codes and a lack of accessibility for those with disabilities. In 2009, a port authority officer for New York and New Jersey reported that a tunnel and bridge agent interfered with her police activities and harmed public safety.

Ostensibly all three of these public employees are whistleblowers, who sought to rectify misconduct, code violations, or safety issues. Still, they all suffered the same fate—they were dismissed from their jobs. These employees faced retaliation for their salutary speech and efforts to improve the public good and, if their allegations are believed, should have had valid First Amendment free speech arguments to challenge their dismissals. But, the bleak reality of modern American law is that such employees often have no valid free speech claim at all. As such, these three employees lost their respective cases before the 3rd, 7th, and 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in recent decisions, one as recently as July.

They lost their retaliation claims under the First Amendment, because of one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in years. That case is Garcetti v. Ceballos. It’s been on the books for more than a decade, wreaking havoc on employees and bastardizing free speech jurisprudence. Those representing employees who have suffered because of the Supreme Court decision have labeled such lower court rulings as being “Garcettized.”

“Garcetti has effectively applauded official oppression, trimmed truth in the public workplace, and done so without moral or workplace-efficiency justification,” longtime Texas-based civil rights attorney Larry Watts told me. “Garcetti is the greatest, judicial enemy of clean government I have seen in my 50 years at the Bar.”

In Garcetti, the Supreme Court created a categorical rule: “When public employees make statements pursuant to their official duties, the employees are not speaking as citizens for First Amendment purposes, and the Constitution does not insulate their communications from employer discipline.” Stated more simply, when public employees engage in official, job-duty speech, they are not speaking as citizens but public employees and have no free-speech rights at all. None. Zero.

The case involved an assistant district attorney named Richard Ceballos, who learned of perjured law enforcement statements in a search warrant affidavit. He wrote a memo to his superiors recommending dismissal of the criminal charges. Instead, he suffered a demotion and a transfer to a less desirable work location.

The case was argued twice before the Supreme Court—once when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was still on the court and once after she had been replaced by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. The court ruled 5–4 against Ceballos, splitting along conservative-liberal lines. The more conservative jurists sided with the district attorney while the four more liberal jurists voted for the employee.

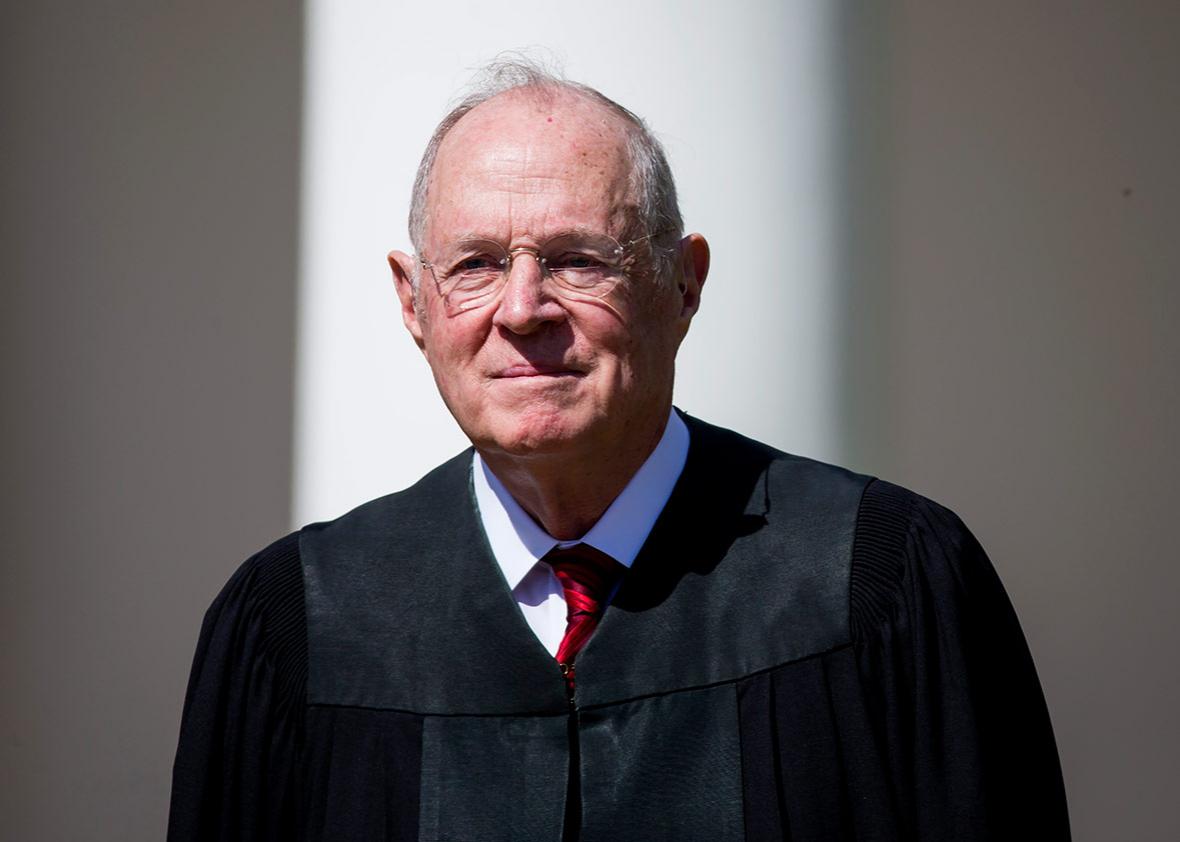

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who often writes passionately about the importance of freedom of speech and thought, authored the majority opinion in Garcetti. It is the black mark of his First Amendment record, a scarlet letter that he should attempt to finally shed.

For decades, the Supreme Court had a workable standard in such free speech cases. Under that framework, the court asked whether a public employee spoke on a matter of public concern or importance, something of larger interest to the community. In other words, was the employee’s speech on a matter of public concern or merely a private grievance?

If the speech was merely a private grievance, there was no First Amendment claim. But, if the speech touched on a matter of public concern—such as speech about racism in the workforce, unsanitary conditions in a school, or brutality against inmates—then courts had to balance the employee’s right to free speech against the employer’s efficiency interests in a disruption-free workforce.

This two-part framework was known as the Pickering-Connick test after two earlier Supreme Court decisions, the 1968 case Pickering v. Board of Education and the 1983 case Connick v. Myers.

But, decades later the Supreme Court imposed the categorical bar in Garcetti, denying any protection if an employee engages in job-duty speech or speaks as an employee instead of as a citizen.

To appreciate the impact of Garcetti, consider the plight of a public school teacher who might be disciplined for classroom speech. Perhaps the teacher speaks about a controversial political matter, offers a different lesson plan, or uses the N-word in an unplanned lecture to students about not using racial slurs.

Lincoln Brown, a sixth-grader teacher in Chicago, learned the power of Garcetti the hard way when the 7th Circuit ruled he had no First Amendment claim for using the N-word in a well-intentioned lecture against such slurs. “Brown gave his impromptu [lecture] on racial epithets in the course of his regular grammar lesson to his sixth grade class,” wrote the 7th Circuit in Brown v. Chicago Board of Education. “His speech was therefore pursuant to his official duties.”

Translation: Lincoln Brown, like so many other public school teachers, had zero free-speech protection for speech in the classroom because of Garcetti.

It’s not just teachers who have lost their free speech rights from the overly broad, categorical rule of Garcetti. Police officers have faced its wrath arguably more than any other group while firefighters and university-level employees have also had to suffer retaliation without recourse due to the ruling.

There have been a few glimmers of hope in recent years. In the 2014 case Lane v. Franks, the Supreme Court refused to apply Garcetti against a university employee who was terminated after providing truthful testimony in a court case. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in her opinion, emphasized the importance of employee speech for the public. Citizens, including public employees, are supposed to testify truthfully in court after all.

Furthermore, two federal circuit courts—the 4th and the 9th—have ruled that Garcetti doesn’t apply to professor speech, because of the additional protection of academic freedom. But, that is only two circuits. As I explained in April testimony to the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution and Civil Justice: “Garcetti threatens the speech of college and university employees. Only two circuit courts of appeals … have explicitly rejected Garcetti as applied to university professors.”

Some lower courts will work around Garcetti, finding that it wasn’t part of an employee’s job—and thus not a part of his public role—to set policy or to criticize certain departmental practices. For example, the 2nd Circuit Court reinstated a police officer’s First Amendment lawsuit in the 2015 case Matthews v. City of New York, finding that the officer spoke more as a citizen when he criticized his department’s arrest quota policy.

But, these are the exceptions.

It has been more than a decade since the Supreme Court dramatically reduced the level of free speech protection for public employees. Various statutory protections are not sufficient to guard against this type of retaliation against whistleblowers. The Constitution is the highest level of law and the first 45 words of the Bill of Rights should not be empty language when applied to public employees. The First Amendment must protect those public servants who have the courage to speak out against corruption, inefficiency, waste, and other problems.

It’s time for the court to reconsider one of its biggest mistakes of recent years. In fact, it’s long overdue.