“It’s Monday, so I brought a special guest.”

So began Sean Spicer’s daily White House briefing for March 27. Moments later, he introduced Attorney General Jeff Sessions—surprise!—who came to the podium with his reading glasses sitting low on his nose and threatened to take funding away from sanctuary cities that shield undocumented immigrants from the federal government. With the White House insignia directly behind him, Sessions spoke with the unmistakable authority of a presidential surrogate.

To a casual observer, Sessions’ drop-in was not particularly notable: just another member of the Trump team stopping by to beat the drum for the administration. But for those steeped in the history and tradition of the Justice Department, the fact that the attorney general had addressed the media from the White House podium—thereby collapsing, literally and symbolically, any semblance of separation between the DOJ and Trump—was a jaw-dropping violation of norms.

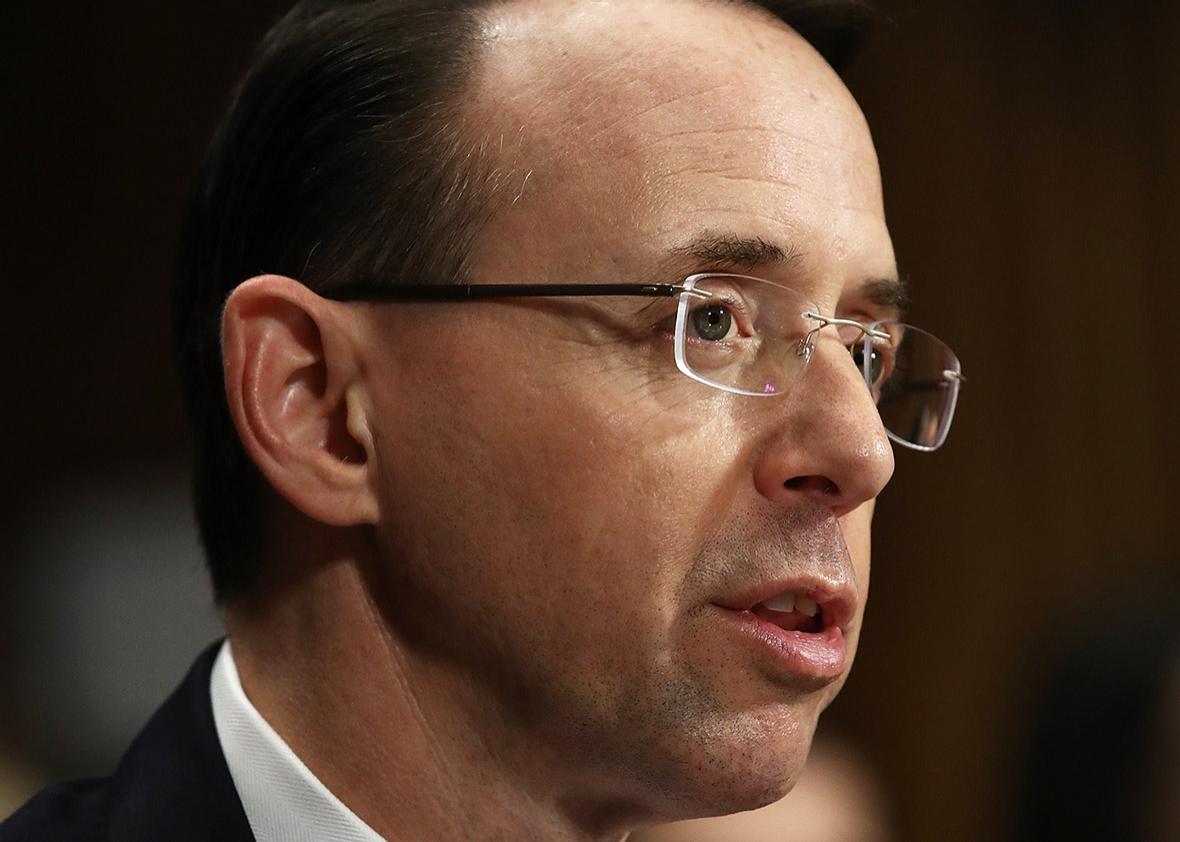

One person who seems to take those norms very seriously is the DOJ’s new second-in-command. Rod Rosenstein—who joined the DOJ in 1990 as a trial attorney in the public-integrity section of the criminal division and most recently spent 12 years as the U.S. attorney for Maryland—is known in legal circles as a consummate professional who has never allowed politics to interfere with his decision-making. The new deputy attorney general was, famously, the only U.S. attorney appointed by George W. Bush who was asked to stay on by Barack Obama—a merit badge that suggests he has been consistently even-handed in dealing with people from both sides of the aisle. It’s a reputation that has attached itself to Rosenstein like a very flattering glue. Practically every profile of him includes words like apolitical, principled, and independent. At his confirmation hearing in March, Maryland Sens. Chris Van Hollen and Ben Cardin called him, respectively, a “fair and focused administrator of justice” and a prosecutor who has conducted himself in “a totally nonpartisan, professional manner.”

In his new job overseeing the DOJ’s day-to-day operations, the 52-year-old Rosenstein is expected to bring a degree of normalcy and structure to an agency that, three months into Trump’s presidency, remains severely understaffed at its top levels. The extent to which he is allowed to assert his principles in running the department—and the extent to which he’s able to exert influence over the attorney general—will be a huge factor in determining what kinds of actions the DOJ takes under Trump and Sessions.

The differences between how Rosenstein and Sessions think about the Justice Department’s role in the federal government are manifest. Where the former seems to buy into an idealized vision of the agency as a nonpartisan instrument of pure law enforcement, Sessions has already demonstrated a gleeful willingness to align himself and his agency with the Trump administration. On April 23, Sessions said, in reference to Trump’s Mexican border wall, “We’re going to get it paid for one way or the other”—a remark that prompted some to wonder who we was supposed to refer to, and what exactly the DOJ had to do with funding anything. Earlier, during a speech to border-patrol agents in Arizona, Sessions declared that the country had arrived in “a new era … the Trump era”—a factually accurate statement, no doubt, but not the kind of thing you want the attorney general saying given that the “Trump era” has already been marked by a pile-up of scandals that the DOJ could play a central role in investigating.

Sessions is, of course, a key member of Trump’s cabinet. He was also an enthusiastic adviser to the Trump campaign back when he was a senator and was the first member of Congress to endorse him during the Republican primaries. On account of that history, and his well-established ideological kinship with Trump, Sessions’ continuing closeness to the president makes sense. And yet there are good reasons to be concerned about a sitting attorney general who is unapologetically loyal to the president.

“There is an inherent tension in the role of attorney general,” said Michael Vatis, who served in the office of the deputy attorney general from 1994 to 1998. “Just like every other cabinet member, he is a political appointee who is supposed to be working the president’s agenda, but at the same time, it’s important for him to maintain a sense of independence from the White House, because inevitably, the Justice Department and the people who work under the AG are going to have to conduct investigations … that have some political element to them.” For those investigations to have credibility, Vatis continued, “you can’t have people in the country thinking … the investigation is not going to be conducted fairly, because the AG is just going to look out for the president’s political interests.”

This is the reasoning that—eventually—led Sessions to recuse himself from overseeing the FBI investigation into the Trump campaign’s possible collusion with Russian efforts to disrupt the 2016 election. As a result of that recusal, the work of leading the Russia investigation has fallen to Rosenstein, who has promised repeatedly to conduct it without regard for any political consequences that may come.

Though some critics of the administration have balked at Rosenstein’s refusal to preemptively appoint a special prosecutor to oversee the Russia probe, his promise to conduct the investigation with integrity should hold some weight. Throughout his career, Rosenstein has spoken forcefully about the importance of keeping the DOJ independent from partisan influence. Asked in 2007 about the Bush administration’s politically motivated firing of seven U.S. attorneys, he suggested to a reporter that protecting the DOJ’s integrity—and maintaining its reputation for being free of partisan influence—is something “employees of the Justice Department should be thinking about in everything that we do.” He continued:

The American public is not able to judge our motives. They don’t know what we’re thinking. They can only observe what we say and do and draw inferences from that. So when information comes to light that gives people reason to be suspicious about the motives of the Justice Department … It casts a shadow on all of our work. That is damaging.

For many career lawyers at the DOJ, as well as alumni who have been watching the Trump administration’s manhandling of their beloved agency with increasing horror, Rosenstein’s hiring is a reason to feel cautiously optimistic about the agency’s future.

“He’s a career DOJ guy,” said one agency staffer, speaking on condition of anonymity. “The career people and the long-termers view him as a known quantity. If they don’t know him personally, they know people who do. If I had to surmise what the rest of the department thinks, I would guess they’re thinking, ‘OK, this is someone we can work with.’ ”

How much power will Rosenstein have as deputy attorney general? Potentially a great deal. “Obviously the attorney general is the final decision-maker and the visionary for the department. He’s in charge. … But the DAG’s office is essentially the nucleus of the department. It’s where major litigation is overseen, and it’s where policy initiatives are led,” said Mónica Ramírez Almadani, who served in the DAG’s office during the Obama administration.

The precise division of labor between the AG and his deputy does vary from administration to administration. One thing that’s been consistently true, though, is that the DOJ’s No. 1 and No. 2 work together very closely. “The DAG and the AG are likely meeting together multiple times a day,” said Thomas Perrelli, who served as the associate attorney general—the department’s No. 3—from 2009 until 2012. “They’re likely doing a national-security briefing early in the day, as well as a morning meeting on any ongoing major issues. And they may meet multiple other times too, either on a particular case or a particular investigation or a particular policy issue. So they’re interacting a whole lot.”

The fact that Rosenstein himself seems to take great pride in his professionalism and independence raises the question of how he will respond when his boss engages in the kind of actions the administration’s critics see as inappropriately political. How far will he be willing to go, for instance, to defend the scores of police chiefs around the country who have argued that the immigration crackdown Sessions is demanding will impede their ability to effectively fight crime? This is what current and former DOJ alumni are waiting to find out: Will Rosenstein serve as any kind of check on the new regime—someone who will tame Sessions’ most aggressive political instincts and push for greater distance between the DOJ and the White House—or will he fall in line and tolerate Sessions’ unabashed cheerleading for Trump?

“It’s going to really depend on the interpersonal relationship that they develop,” said Vatis, now a partner at the law firm Steptoe & Johnson. “That’s a pretty sensitive thing to try to exert influence on, since you’re potentially telling someone that what they’re doing is unethical, or is going to appear unethical.” Advising your supervisor on policy is one thing, he added, “telling him that maybe it’s not a good idea to speak from the White House podium is another.”

Perhaps the best modern-day comparison for the Sessions–Rosenstein relationship is the partnership between Ronald Reagan’s fervently ideological Attorney General Edwin Meese and his relatively mild-mannered deputy, a Democrat named D. Lowell Jensen. In a 1986 article in the New York Times, Jensen was praised for serving as “a buffer between the department’s critics and the outspoken and staunchly conservative Attorney General,” and was credited with consistently stopping Meese from “going too far” in waging “public combat with ideological enemies, particularly on civil rights policies and the Supreme Court’s proper role.” From the Times:

“Lowell Jensen is no ideologue,” said a senior department official who asked not to be named. “He understands the repercussions of our acts in the press and on Capitol Hill.”

Another official said: “You need someone like Lowell, who is essentially nonpolitical, to restrain us when we need restraining. Thanks to him, I think ultimately we get more of what we want.”

It’s hard to say with any confidence that Trump’s AG will be open to absorbing that kind of guidance from Rosenstein. “I don’t know how much influence he’ll have on Sessions,” said Richard Jerome, who worked in the associate attorney general’s office from 1997 to 2001. “[Sessions is] a pretty strong personality, he’s certainly not new to Washington, and he has his own views. There’s not much that’s going to change his approach.”

One important factor to consider is that Sessions probably doesn’t believe that “politicization” of the DOJ is the unforgivable sin that many liberals make it out to be. Indeed, it’s fair to argue that the agency is by definition political and has always been in alignment with the administration it exists to serve. Pretending otherwise, according to this line of thinking, is a form of naïveté: While most people agree that the DOJ should be “nonpartisan” in the sense that a Republican-led agency shouldn’t make it its mission to go after Democrats, the notion that someone like Sessions should try to suppress or hide his ideological priors is a nonstarter. It’s not clear that it’s even possible for the Sessions DOJ to create distance between itself and the White House, considering that the ideas Sessions believes in most fervently—deporting illegal immigrants, reducing drug use through incarceration, and reducing federal scrutiny of local police departments—are the same ones Trump ran on as a candidate, and has embraced as president.

“There’s a mind meld there,” said Leon Fresco, the former head of the DOJ’s Office of Immigration Litigation. “This AG doesn’t have to be asked to get on board with the White House’s policies, since he’s the one who championed those policies [even before Trump was president].”

Still, the AG and the president can be on the same page ideologically without becoming so closely aligned that doing right by the administration becomes more important than doing what’s right. This is the true meaning of “independence”—and in Rosenstein, Sessions has a deputy whose career has been defined by a belief in its importance. Let’s see if he continues to uphold that belief while working in Sessions’ shadow.