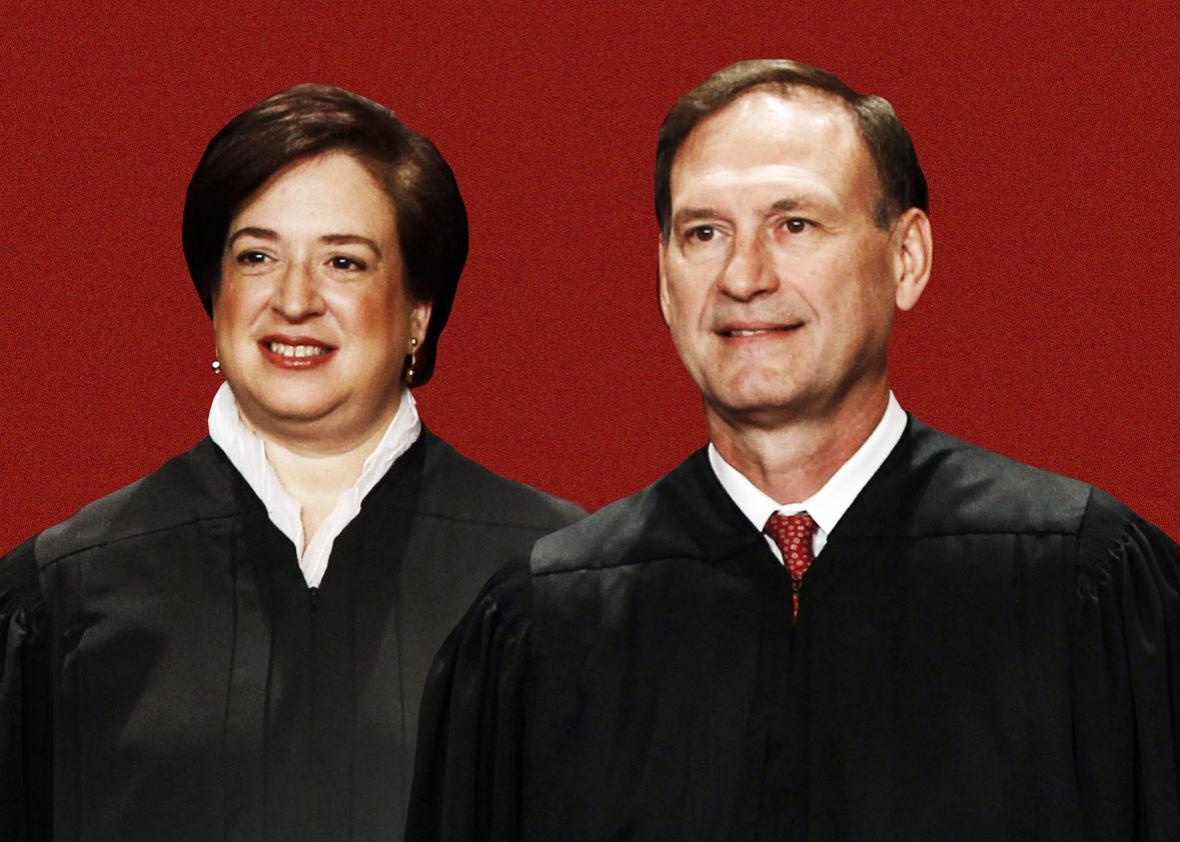

For decades, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia famously maintained a warm friendship despite their fierce ideological disagreements. The two justices attended operas together, traveled in tandem, and dined with each other’s families. Now, at a time when ideological and political disputes are tearing apart friendships and severing family bonds, I’ve started to detect some hints of another unlikely Supreme Court duo. While Justices Elena Kagan and Samuel Alito are not (yet) buddies off the bench, they appear to be developing an amiably disputatious relationship in the vein of Ginsburg and Scalia.

I first noticed the blossoming bond between Kagan and Alito at oral arguments in March 2016. The Supreme Court’s seating chart requires the two to sit next to each other, and like plenty of SCOTUS seatmates before them, the justices often whisper to each other when lawyers at the lectern prattle on. But their conversations are clearly much more than idle chatter; in fact, they seem to delight in making each other laugh. During this particular argument, Kagan made Alito crack up so hard that he covered his mouth with his hand.

Both justices like to chat and love to argue. When Kagan and Alito engage with attorneys at arguments, they sometimes wind up debating one another. Justices aren’t supposed to argue amongst themselves, so they frequently shadowbox through counsel. My favorite example occurred during arguments in King v. Burwell, a challenge to subsidies provided through Obamacare’s federal exchanges. After Kagan unspooled a lengthy hypothetical in an effort to catch the plaintiffs’ lawyer in an inconsistency, Alito co-opted the question and turned it into a softball. When the attorney answered to Alito’s satisfaction, Kagan deadpanned: “He’s good, Justice Alito.”

Both had made their points through counsel, but Kagan got in the last word: If you hijack my question, Sam, I will mock you.

Kagan and Alito appear to have the most fun crossing swords via their opinions. On Monday, the two justices went head-to-head in Cooper v. Harris, a landmark racial gerrymandering decision, with Kagan authoring the majority decision and Alito penning the dissent. In her opinion for the court, Kagan rejected North Carolina’s claim that it had simply used race as a proxy for political affiliation by redistricting along racial lines. Alito accused Kagan of ignoring the state’s key defense, asserting that her analysis “is like Hamlet without the prince.”

In response, Kagan basically called Alito a sucker. Noting that his own account of the case “tracks, top-to-bottom and point-for-point, the testimony of Dr. Hofeller, the state’s star witness at trial,” Kagan wrote “the dissent could just have block-quoted that portion of the transcript and saved itself a fair bit of trouble.” Then, for good measure, she added this mic drop:

Imagine (to update the dissent’s theatrical reference) Inherit the Wind retold solely from the perspective of William Jennings Bryan, with nary a thought given to the competing viewpoint of Clarence Darrow.

Alito and Kagan had a similar face-off in Town of Greece v. Galloway, a 5–4 legislative prayer decision that spurred Kagan to write the best dissent of her career. The court’s five conservatives concluded that the town of Greece, New York, had not favored a particular creed by opening town board meetings with a Christian prayer for nearly a decade. Kagan argued that the town violated the Constitution by “repeatedly invoking a single religion’s beliefs in these settings.” In a concurring opinion, Alito tried to defend the town by arguing, in essence, that it had innocently forgotten to invite non-Christians to deliver the prayer. He called Kagan’s qualms “really quite niggling”—leading Kagan to unfurl this glorious retort in a footnote:

Justice Alito … falters in attempting to excuse the Town Board’s constant sectarianism. His concurring opinion takes great pains to show that the problem arose from a sort of bureaucratic glitch: The Town’s clerks, he writes, merely “did a bad job in compiling the list” of chaplains. Now I suppose one question that account raises is why in over a decade, no member of the Board noticed that the clerk’s list was producing prayers of only one kind. But put that aside. Honest oversight or not, the problem remains: Every month for more than a decade, the Board aligned itself, through its prayer practices, with a single religion. That the concurring opinion thinks my objection to that is “really quite niggling,” says all there is to say about the difference between our respective views.

One pithy footnote—that’s all it took for Kagan to refute Alito’s naiveté. I like to imagine that Alito respected her game.

On Wednesday, I ran my theory of a budding Alito–Kagan frenemy-ship by Eli Savit, who clerked for Ginsburg from 2014 to 2015 and now works as a senior adviser and legal counsel for city of Detroit. Savit, a keen observer of the justices, told me that Kagan and Alito “are similarly wired. Although they come at cases from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum, both are very precise and incisive questioners during oral arguments.” He continued:

If you’re an advocate and Alito or Kagan is asking you a question, you know that they’re driving at something even if you don’t know precisely what it is at the outset. They’re really good at homing in on weak or absurd points in your position. Both are very thorough, very precise in ways that they prepare for and think about case. To some extent you saw this in the Harris footnotes. Those were tremendously consequential footnotes. It’s very clear that each of them appreciated the significance of what was going on here, even though it was below the line.

It’s too soon to tell whether Kagan and Alito’s delightfully spirited debates will blossom into something akin to a Ginsburg and Scalia–style friendship. But the two plainly enjoy locking horns, a sign that they respect and even admire each other’s intellectual firepower. Their jousting draws out subtle nuances in the law and highlights the stakes in each case. And as each justice gains seniority on the court, the opportunity for both to write consequential opinions will only grow. These frenemies will be with us for a long time. Grab some frozen yogurt and enjoy the show.