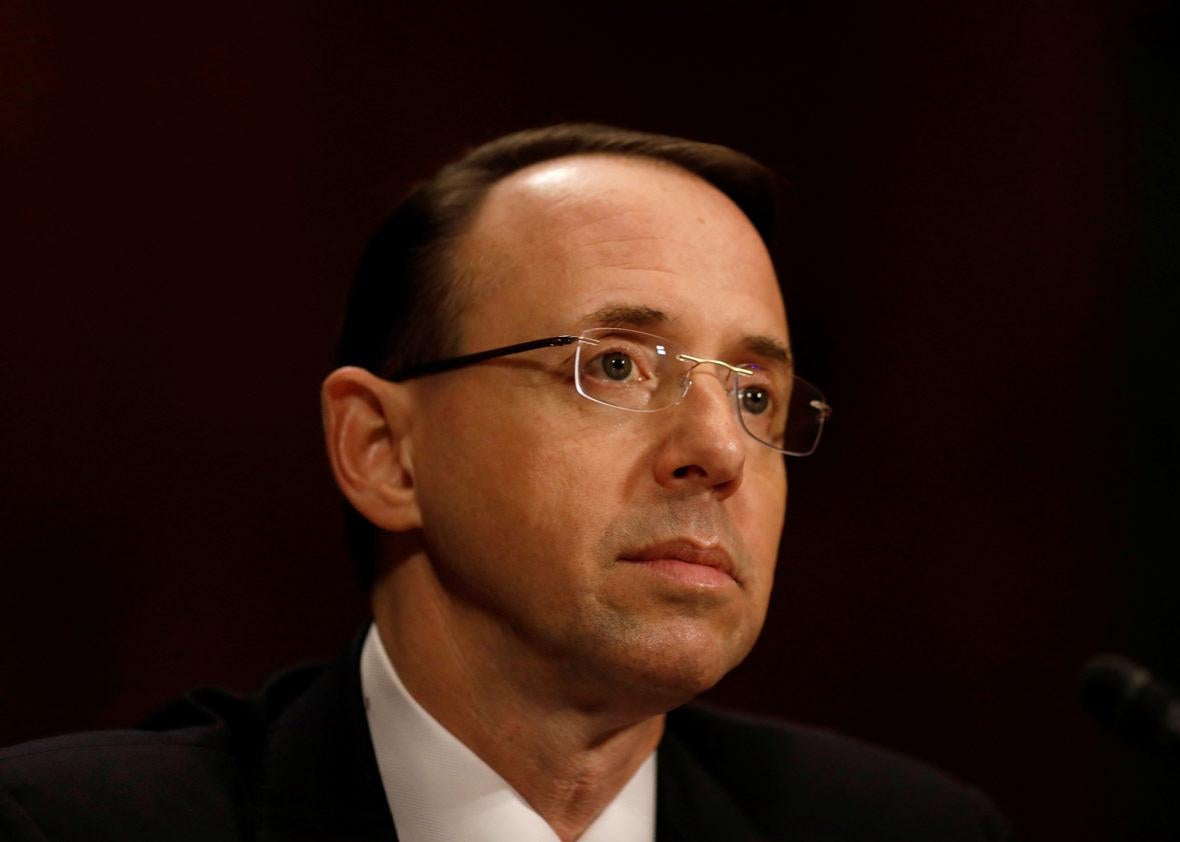

Rod Rosenstein could be making more than $1 million a year right now working at the law firm of his choice. So why is this impeccably pedigreed, widely admired former prosecutor letting himself be humiliated, used, and discredited by Donald Trump?

The answer could be naked ambition: For all the cautious optimism that Rosenstein’s nomination as deputy attorney general inspired in Trump critics, it’s possible the boy scout from Maryland never intended to bring his famous sense of integrity and professionalism to his influential new job at the Justice Department. Maybe he sold himself on the idea that he’d be serving “at the pleasure of the president” and decided he’d do whatever he had to do to keep his boss happy.

That’s one explanation for why Mr. Conscientious wrote that strange memo about James Comey. He knew full well that his sober, serious-minded complaints about the FBI director’s handling of the Clinton email investigation would be used as cover for making a fundamentally corrupt personnel decision, and he decided to lend the president his hard-won credibility the way a guy with a clean record might help a buddy with a checkered past hide a murder weapon.

Maybe I’m naïve, but I have a hard time believing that version of the story. Rosenstein has worked in the Justice Department for too long—27 years—and his reputation in the legal world is too solid for him to be a craven and amoral functionary. It’s more likely, in my view, that Rosenstein went into this job sincerely thinking, or at least hoping, that he could do some good in the Trump administration. Just like all the people who told me they were happy there would be an adult running the Justice Department’s day-to-day operations, Rosenstein probably believed he could be a steadying force at a time when the federal government—and the DOJ in particular—badly needs one.

If you’ll recall, this was exactly the argument that some frightened but optimistic idealists were making in the weeks following Trump’s upset victory in November. Now more than ever, the thinking went, we need people in the administration who know what they’re doing and who are capable of righting the wheel when the impulsive and inexperienced president inevitably steers off the road.

Here’s Ross Douthat, writing in the New York Times three days after the election, on the “moral responsibility to serve” Trump:

For the next four years, the most important check on what we’ve seen of Trump’s worst impulses—his hair-trigger temper, his rampant insecurity, his personal cruelty—won’t come from Congress or the courts or the opposition party. It will come from the people charged with executing the basic responsibilities of government within his administration.

And here’s Yale Law School professor Oona Hathaway, a former Department of Defense official, writing for Just Security:

[O]rganizing from the outside is not enough. We need good people on the inside willing to do the hard work of governing responsibly in the face of immense challenges. Indeed, in many areas, such people can serve as a critical bulwark against ill-considered and dangerous policies.

Assuming, once again, that Rosenstein was not just a secret dirtbag his entire career who has now gone full hack, I suspect he thought of himself as exactly that kind of “critical bulwark.” But what has happened to the deputy attorney general in just two weeks of service feels like proof he underestimated the gravitational pull of Trump’s will to chaos and deception.

At the risk of belaboring events that may by this point be familiar, Rosenstein was asked by Trump on Monday to compose a memo concerning Comey’s handling of the Clinton investigation. That memo—which Rosenstein submitted to his boss, Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and which pointedly stopped short of calling for Comey to be fired—was then publicly described by multiple White House officials as the precipitating factor in Trump’s decision to dismiss Comey. Vice President Mike Pence perhaps went the furthest in leveraging Rosenstein’s good public standing, telling reporters on Wednesday morning that the FBI director had been terminated because “a man of extraordinary independence and integrity and a reputation in both political parties of great character, came to work, sat down, and made the recommendation for the FBI to be able to do its job that it would need new leadership.”

Though Rosenstein has denied reports that he threatened to resign unless this narrative was corrected, it seems clear he wasn’t happy. In addition to marching to the Capitol on Thursday for a mysterious and seemingly urgent meeting with members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, the Wall Street Journal reported that Rosenstein had called White House counsel Don McGahn to complain and “left the impression that he couldn’t work in an environment where facts weren’t accurately reported.”

If Rosenstein is freaking out right now, it’s understandable. On Thursday afternoon, the president himself admitted that, even though he had cited the deputy attorney general’s memo in the brief letter he sent Comey informing the FBI director of his firing, the Rosenstein memo had in fact been of minimal importance in shaping his thinking. With that, Rosenstein’s role in Comey’s ouster was officially downgraded. At the same time, Trump retroactively confirmed his status as a pawn in the administration’s low-rent palace drama. Regardless of how Trump came to his decision, it’s clear at this point that White House officials intended to pin it on Rosenstein until Trump himself gave away the game. The only outstanding question is whether Rosenstein understood the part he was playing, and to what extent he was taken by surprise that his memo led to Comey’s immediate dismissal instead of being merely the first step in a more traditional departmental process.

Writing in Slate back in November, Georgetown Law professor David Luban argued against the idea that reasonable, qualified people who disapprove of Trump should take jobs in his administration. “Don’t tell yourself you can tame the beast, because the beast will tame you,” he warned.

Right now, Rod Rosenstein’s short and depressing tenure as deputy attorney general is the best evidence we have that Luban was right. While the former U.S. attorney does still have a chance to redeem himself by naming a special counsel to oversee the Russia investigation, he must proceed with renewed awareness of what he’s up against. If he’s not more careful than he has been so far, his legacy, at best, will be that of a well-meaning man overwhelmed by filth. Other men and women who find themselves in his position should take note: In an administration guided by the instincts of an angry, would-be tyrant, the line between “critical bulwark” and complicit flunky is thinner than any of us might want to believe.