On Monday, President Donald Trump unveiled his first slate of nominees to the lower federal courts, beginning the process of restocking the federal judiciary following years of depletion. Due to a Republican blockade against President Barack Obama’s later nominees, Trump has inherited more than 100 court vacancies, giving him the power to push the nation’s courts to the right. (Obama, by contrast, inherited 54 vacancies.) Monday’s batch of names suggests that Trump, or at least Trump’s advisers, are taking this job seriously. Thus far, they have selected a roster of 11 smart, talented, and committed conservatives who will likely enjoy smooth sailing in the GOP-controlled Senate.

But Trump’s nominees have more in common than intelligence and ideology: They are relatively young, with an average age of just over 48 years old. That is surely no accident. Like George W. Bush before him, Trump appears to favor younger nominees who will remain on the bench for decades—and serve as a farm team of future Supreme Court picks. With a friendly Senate and a defanged filibuster, this strategy has very little downside for the administration. It ensures that Trump’s nominees will shape American law for generations to come no matter how his own presidency ends.

Not every new administration uses age as a key criterion for picking judges. The average age of Obama’s first 10 nominees, for example, was about 56. The youngest pick, Joseph Greenaway, was 51 at the time of his nomination. The oldest, Andre M. Davis, was 60. Half of the nominees were 57 or older. By comparison, just one of Trump’s first 11 nominees—58-year-old Judge David Nye, who is actually a conservative-leaning Obama holdover—is older than the average nominee in Obama’s first wave.

Obama did go on to nominate younger individuals, though some of them were successfully filibustered. By the end of Obama’s first term, the average age of his appeals court nominees had dropped to 53.5, a number that dipped slightly lower after Democrats abolished the filibuster for district and appeals court judges.

While older judges aren’t necessarily wiser, age can serve as a proxy for other attributes. Older nominees are known quantities often selected because of their political moderation and established reputations within state and local bar associations. Once they surpass the age of 55, they are less likely to be elevated to the Supreme Court and, for that reason, their nominations to the federal bench become less politically controversial.

More veteran jurists are also less likely to exert long-term influence on the judiciary. It takes time and energy to establish a lasting presence on the bench. Judges who have 30 to 40 years left to serve have more opportunity to build up a body of legal ideas and to establish an extended family of clerks who share their judicial philosophies. Think about the influence of Chief Justice William Rehnquist on his former clerk John Roberts, or how Justice Anthony Kennedy molded his clerk Neil Gorsuch. All four of these men were under 50 when first nominated to the bench.

Although younger nominees have less of a track record, they tend to compensate with other attractive qualities. They are usually well-known as rising stars among the party’s legal elite. They are also highly intelligent and superb lawyers entering the prime years of their careers. And perhaps most importantly, they tend to be committed to core principles—otherwise, a presidential administration would be wary about selecting them, given the risk of ideological drift over time.

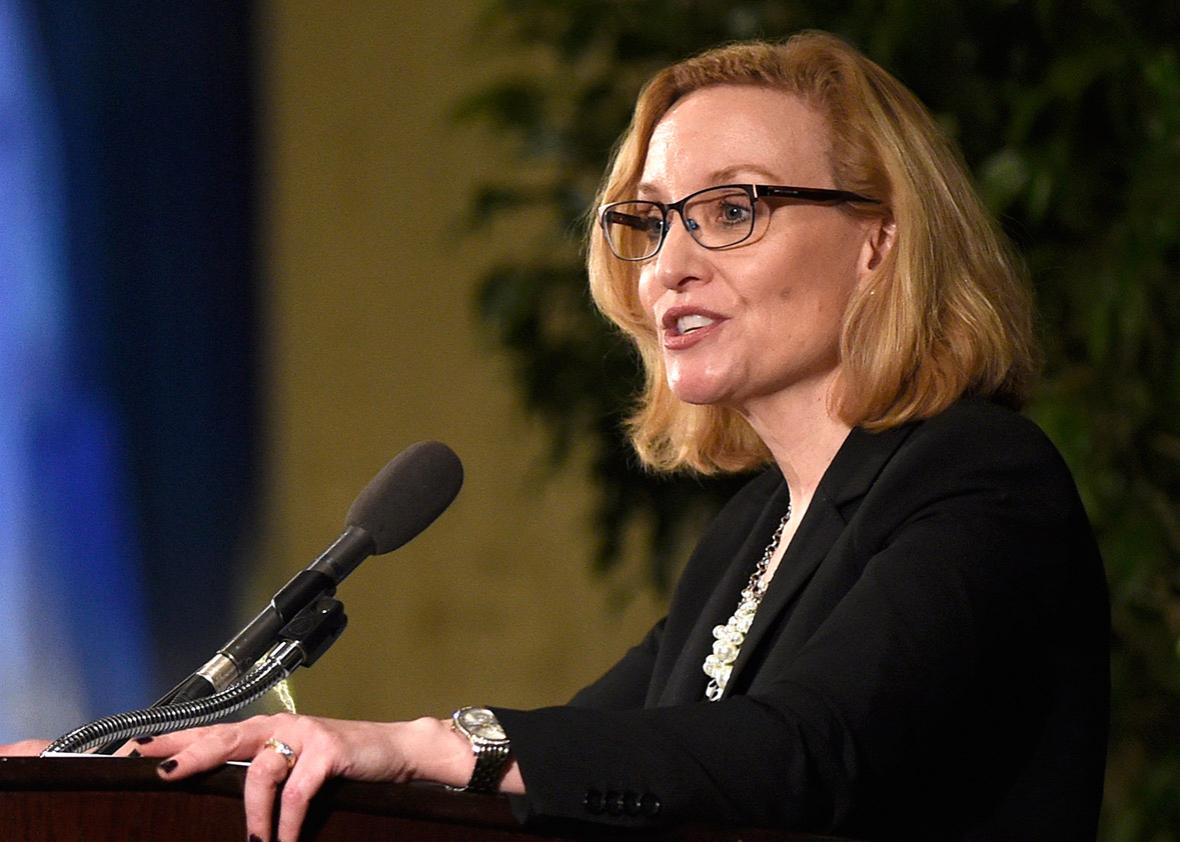

Choosing younger nominees also helps the president prepare for the next Supreme Court opening. Three of Trump’s lower court nominees appeared on the Supreme Court “shortlists” that Trump released during the campaign: Michigan Supreme Court Justice Joan Larsen (48), Minnesota Supreme Court Justice David Stras (42), and U.S. District Judge Amul Thapar (48). Many commentators have speculated that Larsen, in particular, would be a strong contender for the next vacancy, especially if Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg leaves the court. Trump would face significant pressure to replace Ginsburg with another woman, and the other likely option, Judge Diane Sykes of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, is 59 years old. Given the stakes of the next high court battle, Sykes’ more advanced age may be disqualifying.

Trump himself benefited from George W. Bush’s selection of younger judges. When Bush nominated Neil Gorsuch to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Gorsuch was just 38. Eleven years later, Trump was able to put him on the Supreme Court as a relatively spry 49-year-old. The other three men on Trump’s Supreme Court shortlist—Thapar, Thomas Hardiman, and William Pryor—were 38, 41, and 42 respectively when Bush nominated them to the bench. If chosen, any of them could have served (and indeed could still serve) on the Supreme Court for decades.

The Republican and Democratic parties have historically played very different games when it comes to nominating judges to the federal bench. Over the last four decades, the Democrats have been more inclined to pick state and local officials who have paid their dues over decades, while the GOP has worked systematically to identify and lift up legal talent in the rising generation. That difference in strategy will pay clear dividends for Republicans down the road. If Trump’s first 11 nominees retire at the same age as Obama’s first 10 nominees, they’ll each serve eight additional years on the federal bench. Even if the age gap narrows significantly in Trump’s next wave of nominations, there’s no chance it will disappear. Trump’s judges will serve longer than Obama’s. Age matters.

Republicans have long understood that legal ideas have vitality only when they are supported by judges who can articulate and apply them over many decades. It’s a lesson liberals will learn the hard way as they spend the next several decades grappling with doctrines devised by Trump appointees.