Earlier versions of this article appeared at Take Care and Notice & Comment.

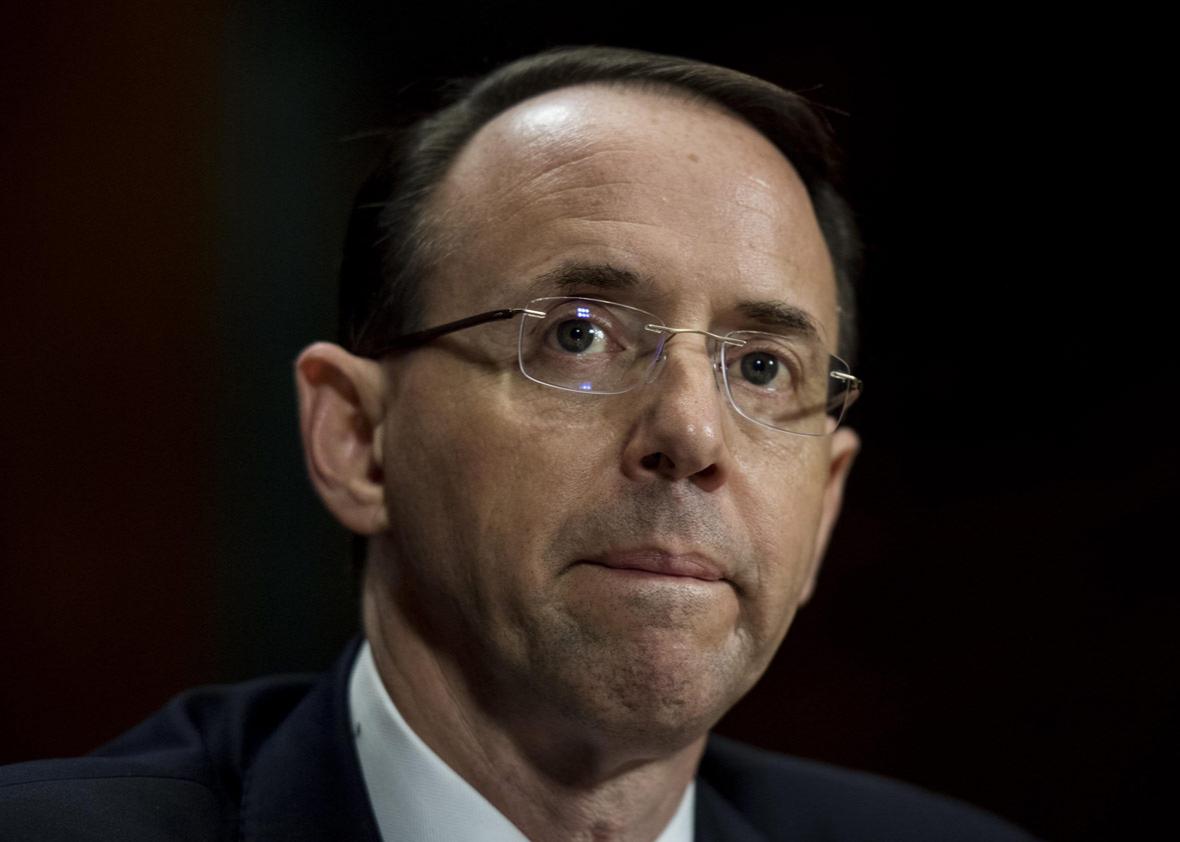

Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein stands at the center of the controversy over the president’s apparent attempt to obstruct an FBI investigation into the Trump campaign’s Russia ties. Rosenstein played a key role in the firing of FBI Director James Comey earlier this month, as well as last week’s decision to appoint former FBI Director Robert Mueller as special counsel in charge of the Russia inquiry. With Attorney General Jeff Sessions having recused himself from the case back in March, Rosenstein is the highest-ranking official in the Justice Department overseeing Mueller’s efforts to uncover how exactly the Russians interfered with the 2016 election, what kind of help they might have received from members of the Trump team, and whether Trump himself has taken steps to cover anything up.

The fact that Rosenstein is both a central character in the story Mueller is investigating and the man responsible for supervising that investigation raises an obvious but underdiscussed question: Should Rosenstein follow Sessions’ lead and recuse himself from the Russia inquiry?

The case for Rosenstein’s recusal grows out of the case for Trump’s guilt. At this point, we have mounting evidence that the president pressured Comey to end the FBI’s inquiry into links between the Russian government and Trump’s top advisers. When Comey refused, the president fired the FBI chief and claimed he had acted based on the “clear recommendations” of Rosenstein and Sessions. Sessions, for his part, said in a letter to Trump that his recommendation was based on “the reasons expressed by the Deputy Attorney General in the attached memorandum.” That three-page memorandum from Rosenstein, in turn, faulted Comey’s handling of the probe into Hillary Clinton’s emails.

Put more bluntly: President Trump stands accused of firing Comey to impede the Russia investigation and then trying to pass it off on Rosenstein.

The Justice Department’s recusal regulation, 28 CFR 45.2, states that “no employee shall participate in a criminal investigation or prosecution if he has a personal or political relationship with … [a]ny person or organization substantially involved in the conduct that is the subject of the investigation or prosecution.” It goes without saying that no Justice Department employee should participate in a criminal investigation if he is himself substantially involved in the conduct that’s under investigation. The subject of Mueller’s investigation (or at least, one significant subject) is whether Trump fired Comey to obstruct justice and then tried to cover it up by enlisting Rosenstein. How is Rosenstein not a person “substantially involved” in that?

Indeed, Rosenstein might have made the most persuasive argument for his own recusal—albeit unwittingly—in a briefing before the House of Representatives on Friday. When House members asked Rosenstein to say who, if anyone, had requested he write the memo justifying Comey’s firing, Rosenstein responded: “That is Bob Mueller’s purview.” In other words, Rosenstein virtually admitted that his role in Comey’s exit would be a subject of the special counsel’s inquiry—an inquiry that Rosenstein continues to oversee.

The case for Rosenstein’s recusal seems so straightforward that one might wonder how the deputy attorney general—widely regarded as a man of integrity throughout his 27-year career as a federal prosecutor—has thus far failed to remove himself from the Russia matter. It’s hard to know what’s going on in Rosenstein’s mind, but there are at least four possible arguments that he might make to justify his nonrecusal.

First, Rosenstein might say that he has removed himself from the investigation already by appointing Mueller, the well-respected former FBI director, to serve as special counsel. But that argument doesn’t hold water, because Mueller remains very much under Rosenstein’s thumb. Under Justice Department regulations, Rosenstein has control over Mueller’s budget and can decide at the start of any federal fiscal year (the beginning of October) to shut down Mueller’s investigation. Moreover, the regulations require Mueller to inform Rosenstein at least 72 hours in advance of any “major development” in the investigation, which includes not only the filing of criminal charges or the arrest of a defendant, but also the execution of a search warrant or an interview with a significant witness “when the events are likely to receive national media coverage” — which here, they surely are. And Rosenstein has the power to order Mueller not to pursue any investigative or prosecutorial step. This is far too much power for someone so close to the center of an investigation to wield over its direction.

Second, Rosenstein might say that as an officer of the Justice Department, he doesn’t count as an “employee” subject to the department’s recusal rule. Notably, Sessions did not rest on this distinction when he recused himself from the Russia probe. But in any event, the Justice Department’s recusal rule reflects the fundamental principle that nemo iudex in causa sua: No man should be the judge (or the prosecutor) in his own case. Whether or not the regulation applies to Rosenstein, the underlying principle certainly does.

Third, Rosenstein might say that Sessions’ recusal renders Rosenstein’s continued involvement in the investigation essential—after all, someone has to remain in charge. But the Justice Department has a protocol in place for how to proceed if both the attorney general and his deputy are recused. Responsibility for overseeing the Russia investigation would fall to the newly confirmed associate attorney general, Rachel Brand. If Brand were for some reason unable to fill that role, then the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, Dana Boente, would be the next in line.

Finally—and this final argument is perhaps the strongest justification for Rosenstein’s refusal to recuse—the deputy attorney general might say that recusal works differently for obstruction of justice than it does for other crimes. If a prosecutor is investigating possible criminal conduct by a suspect, and if the suspect then endeavors to obstruct the investigation, the prosecutor will almost always be a material witness with respect to the suspect’s new crime. But it would be perverse to require the prosecutor to recuse herself at that point: Indeed, it would advance the suspect’s objective if he could disrupt the investigation simply by triggering a transfer of prosecutorial responsibility.

In this case, however, the allegation is not that Trump obstructed Rosenstein’s investigation; the allegation is that Trump was using Rosenstein to obstruct Comey’s investigation. We have no reason to believe that Rosenstein played more than a peripheral role in the FBI’s inquiry prior to Comey’s firing. In other words, recusal might indeed work differently for obstruction of justice than for other crimes, but this is different from the typical obstruction case. Rosenstein wasn’t obstructed in his own probe, yet he might have been employed as a tool to obstruct the FBI.

In short, the justifications for Rosenstein’s continued involvement in the Russia investigation are as inadequate as the three-page memo he wrote to justify Comey’s firing. Rosenstein’s reputation for being a conscientious and honorable public servant is well-earned, and based on that reputation, we might hope Rosenstein will not interfere with the special counsel investigation. But based on that same reputation, we might expect Rosenstein to have recused himself already. If he doesn’t, he will place his credibility into even greater jeopardy.