It has not gone unobserved, at least by me, that I have not spent a good deal of time this term in the Supreme Court. Some part of that is because I am growing fat and lazy. But the more truthful explanation is that while the great joy of my professional life has been to poke fun at serious institutions, the high court has seemed markedly unserious since, through no fault of its own, former President Barack Obama’s court nominee was never seated. For people who held the court out as unique and at least nominally above raw politics, it’s now come to look more and more like the land of misfit jurisprudential toys. Despite all that, it’s fun to be back.

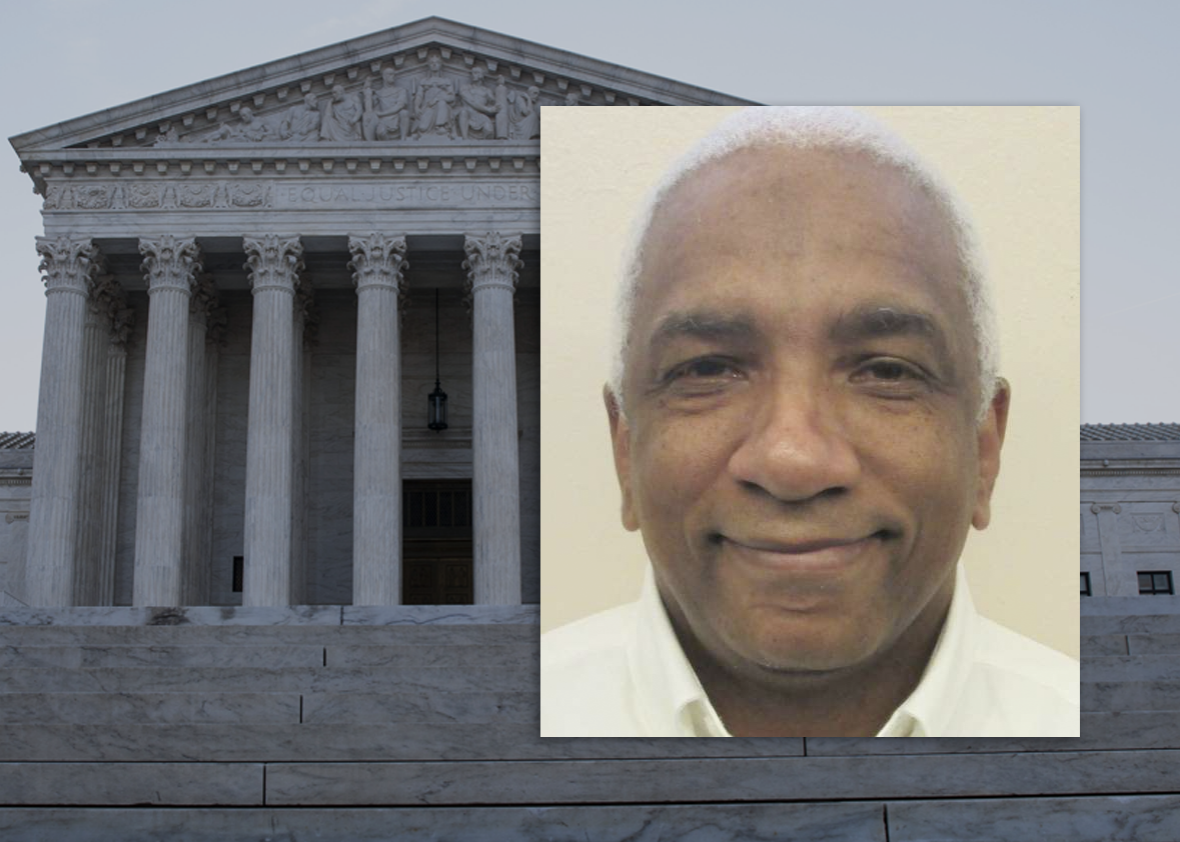

Oral argument this morning in McWilliams v. Dunn looks to be a fairly predictable split between the four liberal justices and the four conservatives, with Justice Anthony Kennedy performing his customary demi-Hamlet at the middle. The appeal probes what kind of expert psychiatric assistance an indigent defendant should be given at trial. The case dates back to a 1984 capital conviction of James McWilliams, who raped and murdered Patricia Reynolds during a robbery at the Tuscaloosa, Alabama, convenience store where she worked.

In a 1985 case, Ake v. Oklahoma, the Supreme Court established that when an indigent defendant’s sanity becomes a major issue at trial, “the State must, at a minimum, assure the defendant access to a competent psychiatrist who will conduct an appropriate examination and assist in evaluation, preparation, and presentation of the defense.” McWilliams was, before his trial in 1986, assessed by three doctors on an Alabama “lunacy commission” (yes, it was called that) who concluded he was fit to stand trial and that there were no mitigating circumstances that should influence his case. At his trial, his court-appointed counsel put both McWilliams and his mother on the stand to testify about mental health issues related to a childhood head injury. But McWilliams had no expert to testify on his behalf. The jury found him guilty and voted 10-2 for the death penalty. (In Alabama, the judge can hold a separate sentencing hearing.)

Records McWilliams had subpoenaed from prison never showed up before his trial. But just before the judge sentenced him, those records, plus a detailed report from a court-appointed psychologist, Dr. John Goff, who assessed McWilliams after trial, were handed over to the judge, prosecutor, and defense counsel. Goff, straying from the findings of the “lunacy commission,” had concluded that McWilliams had “organic brain dysfunction,” and his 1,200 pages of prison records revealed that he was being treated with strong psychotropic medications. This all seemed sort of new and important.

So, at McWilliams’ judicial sentencing hearing, his defense counsel begged for a mental health expert to help understand the voluminous records he’d been provided only hours earlier, saying he couldn’t offer up mitigating evidence, because he didn’t even understand the evidence. The judge gave him three hours to look over the records at lunch. After the defense asked to withdraw the records from the trial (refused) and asked for a continuance to study the material (refused), the trial judge sentenced McWilliams to death. On the question of McWilliams’ mental health, he determined the defendant was “feigning, faking and malingering.”

The issue at the Supreme Court today is simply whether the right to the kind of expert assistance granted in Ake—“to conduct a professional examination … to help determine whether that defense is viable, to present testimony, and to assist in preparing the cross-examination of the State’s psychiatric witnesses”—demands something more than what McWilliams received, a neutral expert dumping files on the counsel table right before trial. The Alabama courts and some federal appeals courts have taken the position that the mental health expert needn’t be “independent” of the prosecution, and that indigent defendants aren’t entitled to have experts that side solely with them. The trickier question is whether or not the requirement that your expert be truly helpful is “clearly established” case law that can be used to set aside the capital conviction. This whole issue took on greater urgency last week, when two Arkansas death-row inmates—Don Davis and Bruce Ward—saw the Arkansas and U.S. Supreme Court block their executions, which had been scheduled for last Monday, until McWilliams is decided in June.

Which means that back on the island, the misfit toys are quarreling.

Stephen Bright—representing McWilliams at oral argument—is immediately confronted by Justice Anthony Kennedy, who isn’t persuaded that the rule McWilliams is seeking is a “clearly established right” sufficient to overcome the procedural bars in death-penalty cases.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who has become ever more voluble and truly pissed off in her work in the death-penalty space, notes that here, there was evidence “at the last moment … that certain signs of organic brain injury were present, and once that was confirmed, what the expert was saying to the court is ‘now I need help.’ ”

Justice Samuel Alito presses Bright: “You seem to be arguing that what the defendant is entitled to is an expert who will function, more or less, like the kind of expert who would be retained by the defense, if the defense were simply given funds to hire an expert.” Bright replies that the system is imbalanced:

The prosecution can hire as many experts as it wanted. … It can choose experts that will come out the way it wants. If you’re in Texas and you want to prove future dangerousness, doctors will testify every single time they get a chance that the defendant is a future danger.

Bright explains that the word “partisan” expert is a misnomer: “Of course, parties, whether it be the prosecution, whether it be a wealthy criminal defendant, whether it be a wealthy civil litigant, are all going to hire partisan experts. They’re going to hire the experts that they think will give them the opinion that will help their side of the case.” But here, Bright says, his client is hardly asking for the moon: “He doesn’t get a partisan expert. He doesn’t get to choose the expert, but he gets a competent expert to give whatever advice that expert can give to him as he prepares his defense and as he prepares to deal with the prosecution case.”

Kennedy seems concerned that a neutral expert can’t be effectively helping both sides, and Bright agrees that mental health experts “can’t work both sides of the street.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch asks Bright whether Ake implies that a neutral expert would be acceptable, instead of one dedicated to helping the defense. Bright replies “That was the old days. Those were the horse-and-buggy days, and this is today. And today, mental health is hotly contested. It takes experts on both sides.” Bright notes that “experts widely disagree on mental health.”

Gorsuch retorts: “Experts widely disagree on everything. That’s why you hire them … And why they cost so very much.”

Alabama’s Solicitor General Andrew Brasher has 30 minutes to argue for the state, and it’s immediately clear that the court’s four liberal justices aren’t comfortable with what happened to McWilliams. Justice Elena Kagan asks Brasher to “focus on the money sentence in Ake.” She notes that the case explicitly says: “We hold that when the defendant makes this preliminary showing that mental health is going to be at issue, the State must assure the defendant access to a competent psychiatrist who will assist in evaluation, preparation and presentation of the defense.” “Assist!” she says. “Assist!”

Brasher replies that “neutral experts are capable of assisting the defense in a way that an expert assists the defense.” Kagan replies, “They’re capable in the sense that sometimes they might, but it’s not somebody who sometimes might, and is capable of, but who, in fact, will do so, to the best of his ability, assist the defendant.”

Brasher reiterates that Goff, the doctor who prepared the voluminous report right before McWilliams’ sentencing hearing, “was his expert.” Neither Stephen Breyer nor Kennedy appear persuaded that Goff behaved like one. Brasher urges that McWilliams could have used him as one and chose not to. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg notes that in virtually every jurisdiction today, it is understood that “Ake requires an expert who will be, essentially, part of the defense team.” This includes the Supreme Court of the state of Alabama, “which in 2005 ruled an indigent defendant is entitled to an independent expert devoted to assisting his defense, not one providing the same information or advice to the court and prosecution.” Brasher replies that the lower courts and states have adopted that rule over time, but it doesn’t mean it was the “clearly established” holding in Ake or that it compels the court to expand Ake to mean that today.

Remember last week when, at his first day at the high court, Justice Gorsuch was slapped delicately on the nose with a newspaper by Elena Kagan, and everyone went nuts? Again today, she bops him gently, this time when he suggests we can limit the holding of Ake to the relief the party asked for in their appeal. Gorsuch adds that in Ake, the defendant asked only for “a partisan expert or a court-appointed expert. But would have been satisfied with either one.” So isn’t it over right there?

Brasher starts to respond in the affirmative, but Kagan swoops in with her rolled-up newspaper: “That would be quite something, I have to say, General. If we say: ‘Listen, when you read our opinions and when you try to figure out what we’re saying, what you have to do is go back to the [question presented] and just narrow it to exactly what the QP said.’ I think that that would be a shocking way to interpret this court’s opinions.”

“Shocking.” Ouch. Good thing that group dinner at the White House got rescheduled.

In his rebuttal Bright says at stake in this case “is the proper working of the adversary system. And this certainly doesn’t put the defense in an equal position with the prosecutor, not by a long shot, but it at least gives the defense a shot, at least gives them one competent mental health expert that they can talk to, understand what the issues are, present them as best they can.”

The high court has been slowly ruling in favor of limiting capital punishment in some extreme death-penalty cases this term. Because the psychological assistance that indigent defendants now get is so much more substantial than it was 30 years ago, cases like McWilliams will become increasingly rare. Correcting egregious errors from decades ago is hardly going to mean the end of capital punishment, as is plain from the push for executions in Arkansas this month. But this seems as good a time as any for the court to recognize that poor people in prisons have exceedingly pressing mental health needs. A recent Bureau of Justice Statistics report estimates that 64 percent of local jail inmates, 56 percent of state prisoners, and 45 percent of federal prisoners have serious mental health illnesses. That we had “lunacy commissions” only 30 years ago isn’t the only piece of lunacy in this case. It’s that people who were poor and mentally ill were afforded no assistance in proving it, and we’re still fighting about that.

Even on this island of misfit jurisprudential toys, that level of absurdity ought to mean something.