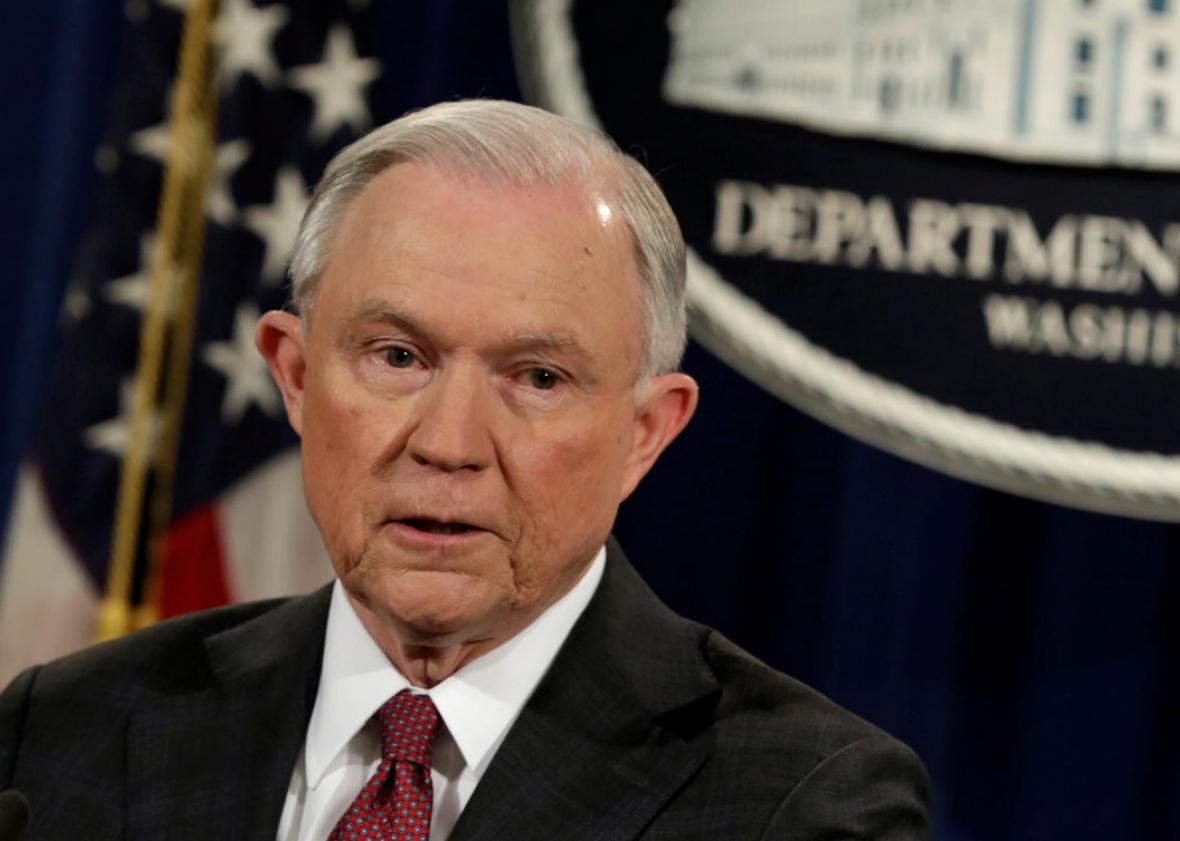

Who will protect the Obama administration’s hard-fought efforts to fix America’s most dysfunctional police departments now that Attorney General Jeff Sessions has made it clear he wants his Justice Department to rein those efforts in? The same people who have already served as a check on Donald Trump: federal judges.

In a March 31 memo sent to DOJ department heads and U.S. attorneys, Sessions ordered a review of “all Department activities” to make sure they align with Trump’s platform of being superficially pro–law enforcement. Those activities include more than a dozen so-called consent decrees, which are legally binding, court-ordered agreements that the Obama-era Justice Department entered into with cities—among them Cleveland; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and New Orleans—in which police officers were found to have routinely violated the Constitution.

These agreements have all come out of intensive investigations, carried out by the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, into the patterns and practices of troubled police departments. They are designed to compel local law enforcement leaders to pursue change on a set schedule. They can also put pressure on city officials to provide funding for reform efforts and training. Consent decrees have power because they are supervised by a tag-team duo of an independent monitor, who files regular reports on the department’s progress, and a federal judge, who has the power to hold the city in contempt and impose sanctions on it if the terms of the agreement are not being honored.

In an interview, former Civil Rights Division official Christy Lopez told me these judges will likely be an important obstacle if Sessions moves to dissolve existing consent decrees or change their terms to make them less demanding. Other DOJ alums I spoke to said the same thing. “As long as the judges stand strong, these jurisdictions will stand strong,” said Jonathan Smith, a longtime Civil Rights Division attorney who now serves as executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs.

In some jurisdictions that are currently under consent decree, the cause of reform has been publicly embraced by city politicians and police officials. For example, in Baltimore, the mayor joined with the police commissioner Tuesday in declaring that the reforms mandated in a proposed agreement with the DOJ “are going to take place no matter what.” As reported in the Baltimore Sun, city leaders declared their support for the consent decree after learning of the DOJ’s decision to delay a key court hearing pertaining to the proposed agreement.

In some cities with negotiated consent decrees, local officials likely won’t be quite so enthusiastic about change and will in fact be relieved that the new DOJ won’t push them as hard as the old one. Here’s how Roy L. Austin Jr., who worked on law enforcement issues in the Civil Rights Division for four years under Obama, explained it to me:

The way it usually works is, say you’re looking at [a specific provision] of a consent decree. The city might come in and say, “OK, we’ve done everything we needed to do on this.” The government might say, “No, the city has not.” And then the independent monitor can weigh in one way or another and provide advice to the judge, and then you have a healthy debate about it with people who are coming to it from slightly different perspectives. What [the Sessions DOJ] can very easily do is just not push back on cities that say they’re in full compliance even when they’re not.

In that scenario, it’ll be up to the judge to do the pushing back—essentially, to insist that the city do more than the Sessions DOJ demands of it. According to Chiraag Bains, who spent about seven years in the Civil Rights Division before leaving in January, judges who find themselves in that situation will have the power to impose sanctions on a city unilaterally, without the DOJ asking them to. “DOJ has an important role, along with the monitor, in alerting the judge to the city’s progress or lack of progress,” Bains said in an email. “If DOJ isn’t doing its job or is being too lenient, the judge needs to be paying close attention to see through that and understand when a city is dragging its feet, blowing deadlines, and failing to fulfill its court ordered obligations. And if the jurisdiction hasn’t complied, the judge doesn’t need to wait for DOJ to move for contempt or sanctions.”

Civil rights leaders seem optimistic that in most of the jurisdictions that are currently under consent decree, judges will rise to the occasion—especially if local community members encourage them to press ahead with reform. “The courts are sensitive on matters of great public concern,” said Jonathan Smith. “If the judge hears from the residents of the city that they feel strongly about the consent decree remaining necessary … I think it’ll have a heavy influence.”

An early glimpse at how judges might be thinking about the Obama DOJ’s consent decrees came in January, a few weeks before Trump was sworn in as president. At a hearing concerning the consent decree in Cleveland, an agreement that addressed excessive use of force, poor training, and lack of discipline in misconduct cases, then–U.S. Attorney Carole Rendon asked Judge Solomon Oliver Jr. to comment on “the notion that has been swirling out there about what [the] change of administrations might do.” Judge Oliver responded unequivocally:

This case didn’t start yesterday. This case was investigated. This case was negotiated, and the city and Justice Department came to the conclusion that this was the best thing to do. This is now an order of the court. … This is not a matter for the executive to change or to cause it to move in a different direction. That’s my view.

There’s reason to think other judges share this mindset. “In the majority of [open] cases, the judges are quite good,” said Smith. “Some have been much more hands off than others, but in the significant cases—Seattle, New Orleans, Cleveland, Newark, [New Jersey], Puerto Rico, you’ve seen judges who have played a very significant role.”

Back in January, the Trump administration pushed to implement another one of Sessions’ pet ideas: introducing extreme new restrictions on immigration from Muslim-majority countries. In that case, several federal judges stopped the plan in its tracks, delaying the implementation of the executive order because it likely violated the Constitution. The work of preventing Sessions from fully realizing his other pet idea—that the police reform plans put in place by the Obama-era Civil Rights Division are harmful to law enforcement and must be dismantled—is going to fall to them as well.