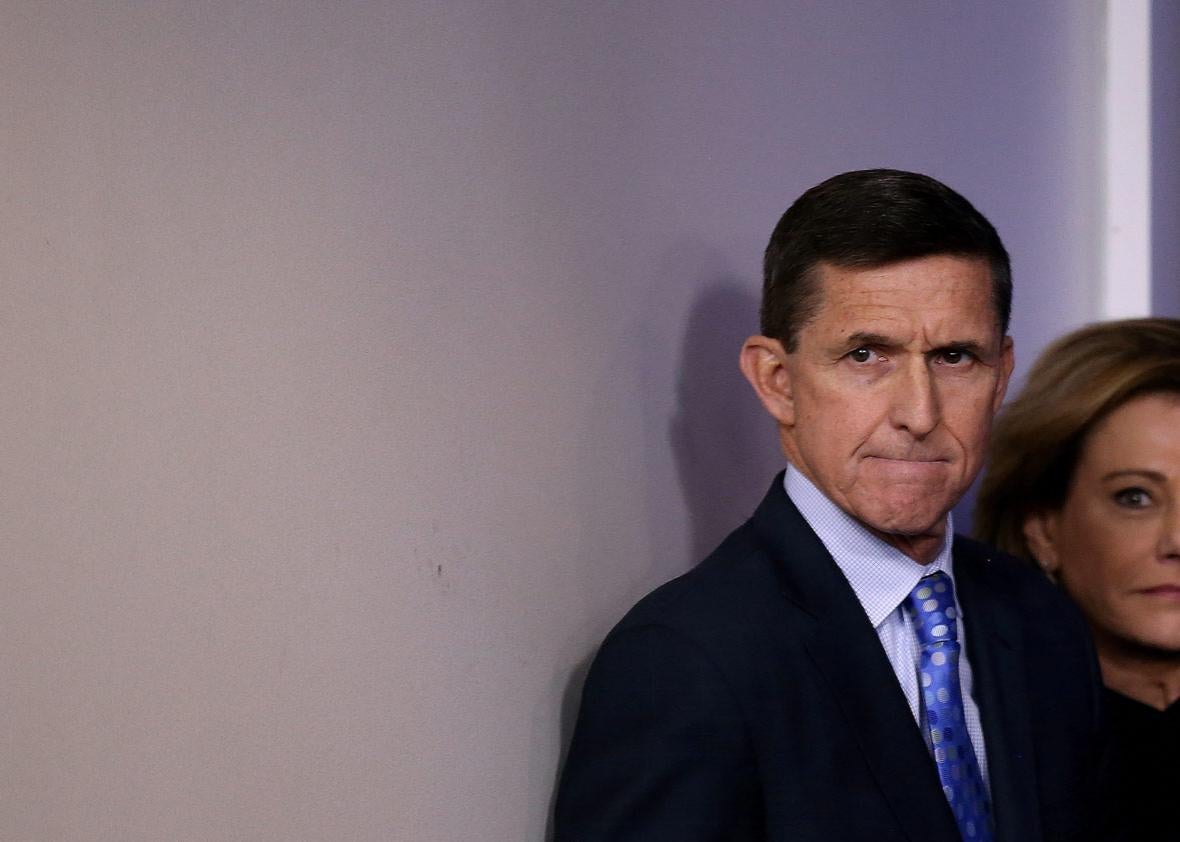

News leaked on Thursday evening that retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn was shopping his testimony regarding the Trump administration’s Russia ties to anyone who might listen. Specifically, the former national security adviser is saying he’s willing to talk to the FBI and both the House and Senate intelligence committees. The price? In his lawyer’s words, “assurances against unfair prosecution.”

Whether Flynn deserves the requested immunity or not, or whether he will get it, and from whom, all remain unanswered questions. At this point, the Justice Department and Congress—which has its own narrow immunity authority—should probably decline Flynn’s bid because they know too little about the matter to judge whether Flynn’s price is right. (The reporting thus far is that he’s found no takers.)

Based on what’s been publicly reported, Flynn faces a long list of potential federal charges. Flynn’s conversations with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak arguably violate the Logan Act, an arcane federal law prohibiting diplomacy by private citizens. These conversations happened during the transition and Logan Act violations are almost never prosecuted, so Flynn probably has a good defense.

But various media reports suggest Flynn was evasive in interviews with federal law enforcement officials; any false statements could also be a crime. Last month, Flynn’s lawyers also filed retroactive registrations regarding Flynn’s foreign consulting work with the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act—the failure to file these documents in a timely fashion could also be prosecuted. This same foreign consulting work also creates risk under the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause, which applies to retired military officers and requires a congressional waiver for certain foreign work.

Finally, Flynn may face legal risk if he failed to disclose these foreign contacts as part of his top-level security clearance applications. Not to mention potential legal risk relating to Flynn’s reported conversations with Turkish officials regarding whether a Turkish cleric could somehow be spirited out of the U.S.—conversations that could, in theory, be construed as conspiracy to commit federal crimes.

An obvious but important starting point: The Justice Department probably doesn’t need Flynn’s testimony if it wants to potentially charge him with any of these offenses. It already has the transcripts of intercepted conversations with the Russians, interview notes with Flynn, legal filings by Flynn, and security clearance applications from Flynn. (Also, you normally don’t offer to testify in exchange for immunity if you think that investigators don’t independently have the goods on you.)

The most important thing to think about is this: Prosecutors don’t give immunity to get confessions; they give immunity to help build bigger cases against bigger potential defendants. For the Justice Department or Congress to take Flynn’s offer, he must offer something—or someone—they don’t already have. And it should either be someone higher up or someone who may have committed a more serious crime. Another very key point is that most immunity offers are made less publicly, following a “proffer session” in which the potential defendant unveils the goods and gives investigators a chance to decide whether the testimony is worth the price of immunity.

In the Justice Department, normal immunity transactions get decided by the assistant attorney general in charge of the criminal division. Because of this matter’s sensitivity, and the attorney general’s recusal, the Flynn case will likely hit the desk of Acting Deputy Attorney General Dana Boente—or Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, once he’s confirmed. On the congressional side, committees conducting investigations can vote to grant immunity to witnesses. However, such decisions must be somewhat bipartisan in that they require a two-thirds vote.

Since the government probably doesn’t need Flynn’s testimony to charge him, that means he would have to have valuable information relating to something or someone else. And since Flynn is already a pretty big catch for prosecutors in his own right, he would have to offer someone or something even bigger for an immunity deal to make sense.

So what does Flynn have to offer? In Just Security, Harvard law professor and former prosecutor Alex Whiting speculates that the very public manner of Flynn’s offer suggests he has little of value to give, certainly nothing that would attract federal prosecutors. Rather, Whiting writes, Flynn maybe hoping to entice or pressure Congress into granting immunity under its authority, and do so in such a way that complicates any future federal prosecution. (Maybe he’ll get some help on the pressure front, given that his former patron in the White House—President Trump—is publicly backing an immunity deal.) Given the significant legal risk Flynn faces, this may be a rational move by his lawyers. However, it all depends on how central congressional investigators think Flynn is to their Russia inquiry—or if Congress even moves to conduct a meaningful and far-reaching inquiry, something in doubt after the House Intelligence Committee’s implosion earlier this week.

Could Flynn offer something else? To date, news reports have implicated former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, former Trump policy adviser Carter Page, and outside adviser Roger Stone for their varying levels of Russia-related activity. (Each has denied any wrongdoing.) Manafort, Page, and Stone matter because of their roles on the campaign and ties to the president—but Flynn arguably outranked them, both in terms of his administration role, and his value to prosecutors. Unless Flynn has information that relates to other principals, including President Trump’s inner circle or the president himself, his testimonial offer will likely fall flat (unless of course some of these other actors did way worse things than Flynn might have done).

Flynn and his lawyers may be gambling on the timing of their offer here. Congressional inquiries into the Trump administration’s Russia ties have broken down, thanks largely to a blizzard of strange behavior by House Intelligence Committee Chair Rep. Devin Nunes. The Senate Intelligence Committee appears to be moving forward with its own bipartisan inquiry, and Flynn’s testimony might be attractive to Senate investigators. Indeed, the less the White House cooperates, or the more it acts to block witnesses from testifying, the more valuable Flynn’s testimony may be to congressional investigators. However, Justice gets a vote in these immunity grants, and can delay—if not altogether block—Congress from granting immunity while its law enforcement investigations are underway. That would almost surely happen here even if Congress were interested in this offer.

This thin reed of hope that Flynn’s testimony may be attractive to congressional investigators was probably enough to motivate his lawyers to offer testimony in exchange for some grant of immunity. It may be the only hope Flynn has left after being publicly defenestrated 24 days into the Trump administration, although this reed is rapidly thinning as House and Senate intelligence committee members express skepticism about any grants of immunity. (Rep. Adam Schiff, the ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, said on Friday that he would need to see a proffer from Flynn, plus additional background documents, before considering any granting of immunity.)

The saddest part of the statement from Flynn’s lawyer comes in the third paragraph, which describes Flynn’s long (and largely successful) career as an Army officer, culminating in his retirement as a three-star general. The contrast between that brilliant career of public service, and Flynn’s current predicament, could hardly be more stark. Even if Flynn’s immunity gambit succeeds and he avoids criminal prosecution, his actions after retirement will still have done grave harm to himself, his reputation, and the American profession of arms.