It is as yet unclear if all the strange “fixes” that have been built into President Trump’s Travel Ban 2.0 will get around the constitutional infirmities of the original. It remains to be seen if the Establishment Clause and Due Process objections raised in courts nationwide can be erased in time through litigation. But perhaps the strangest repair in Monday’s rebooted order is the effort to connect the travel ban to actual episodes of terror.

The new Executive Order now provides:

Recent history shows that some of those who have entered the United States through our immigration system have proved to be threats to our national security. Since 2001, hundreds of persons born abroad have been convicted of terrorism-related crimes in the United States. They have included not just persons who came here legally on visas but also individuals who first entered the country as refugees. For example, in January 2013, two Iraqi nationals admitted to the United States as refugees in 2009 were sentenced to 40 years and to life in prison, respectively, for multiple terrorism-related offenses. And in October 2014, a native of Somalia who had been brought to the United States as a child refugee and later became a naturalized United States citizen was sentenced to 30 years in prison for attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction as part of a plot to detonate a bomb at a crowded Christmas-tree-lighting ceremony in Portland, Oregon. The Attorney General has reported to me that more than 300 persons who entered the United States as refugees are currently the subjects of counterterrorism investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

(Emphasis ours.)

This is evidently an effort to cure the defect found in various reviewing courts, which could find no connection at all between the seven targeted countries—Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen—and specific allegations of terror attacks. (This new executive order reduces that number to six, as Iraq has been excised from the list.) As Judge Leonie Brinkema of the Eastern District of Virginia noted in her Feb. 13 order granting the Commonwealth a preliminary injunction against the first executive order:

[T]he only evidence in the record on this subject is a declaration of 10 national security professionals who have served at the highest levels of the Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the National Security Council through both Republican and Democratic administrations. … They write, “We all agree that the United States faces real threats from terrorist networks and must take all prudent and effective steps to combat them, including the appropriate vetting of travelers to the United States. We all are nevertheless unaware of any specific threat that would justify the travel ban established by the Executive Order issued on Jan. 27, 2017. We view the Order as one that ultimately undermines the national security of the United States, rather than making us safer. In our professional opinion, this Order cannot be justified on national security or foreign policy grounds.”

They also observe that since Sept. 11, 2011, “not a single terrorist attack in the United States has been perpetrated by aliens from the countries named in the Order.”

Last month’s 9th Circuit order made the same point. As the three judges unanimously noted, the “Government has pointed to no evidence that any alien from any of the countries named in the Order has perpetrated a terrorist attack in the United States. Rather than present evidence to explain the need for the Executive Order, the Government has taken the position that we must not review its decision at all.”

Throughout the earlier litigation, judges who implored Department of Justice lawyers to provide evidence of a connection between the seven nations and an increase in domestic terror attacks were told either that no such numbers existed or that such information could not be shared with the courts.

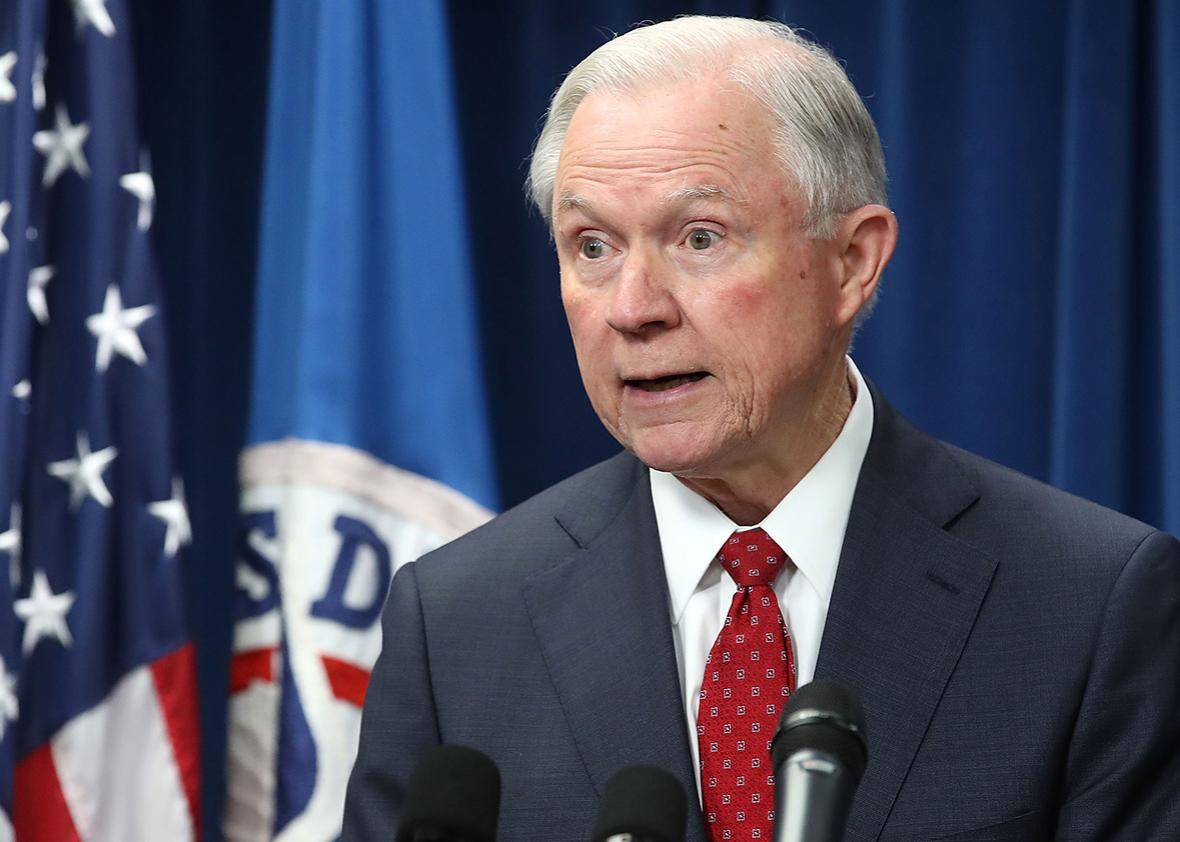

On Monday, however, we were afforded new so-called proof, or at least a new allegation—that “more than 300 persons who entered the United States as refugees are currently the subjects of counterterrorism investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.” According to Fox News, which cites a Department of Homeland Security official, this accounts for “nearly a third of the 1,000 FBI domestic terrorism cases.” (It is unclear whether these 1,000 cases are currently extant, or what time span they cover.) Speaking at a news conference on Monday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions confirmed this “more than 300” statistic.

There are a huge number of problems with this claim.

First, it directly contradicts leaked reports from the Department of Homeland Security—revealed by the Associated Press on Feb. 24—that found little evidence that citizens of the seven countries targeted in the original travel ban posed any greater terror threat to the United States. In fact, last week’s draft DHS report determined that few people from the countries in the original travel ban have carried out attacks or been involved in terrorism-related activities in the United States. Justice Department spokespeople are now contending that the leaked DHS report was an early draft.

Second, there is absolutely no connection between these “more than 300 persons” and the countries listed in Trump’s travel ban. While the executive order says these potential terrorists came to the United States as refugees, it doesn’t indicate where these “more than 300 persons” came from, and thus doesn’t provide any rationale for barring people from Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.

Third, the two specific examples cited by the executive order are both bogus. One case is that of “two Iraqi nationals admitted to the United States as refugees in 2009”—the famed “Bowling Green massacre” incident. Given that Iraq has been exempted from this new travel ban, citing this case actually weakens the argument that the Trump administration has specifically chosen countries that breed terrorists. Moreover, whatever else it represented, the “Bowling Green massacre” was assuredly not an attack by foreign nationals on American soil. The other case is that of “a native of Somalia who had been brought to the United States as a child refugee.” Since this individual came to the U.S. as a child, it’s hard to understand how a temporary travel ban to allow for more intensive vetting would have affected this particular case either, a point emphasized in last week’s leaked DHS documents.

Fourth, those two specific examples—neither of which is relevant—are literally all we have to support the administration’s claim that “more than 300 persons … are currently the subjects of counterterrorism investigations.” Given the bad examples we do have, we should be very, very cautious about accepting that “more than 300” number.

Fazia Patel, co-director of the Liberty & National Security program at NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, notes that we also don’t know what “counterterrorism investigations” means in this context. There is a massive difference, Patel tells me via email, between what’s known as an “assessment” and a full investigation. “An assessment is an early-stage investigation which does not require suspicion of criminal activity, but rather can be started by an agent with an ‘authorized purpose,’ ” she explains. The vast majority of assessments never lead to full investigations. In 2011, the New York Times reported that the FBI conducted 11,667 assessments between December 2008 and March 2009, only 3.7 percent of those led to full investigations, and a small proportion of those investigations led to convictions.

Finally, Patel says we should be cautious in interpreting the executive order’s claim that “hundreds of persons born abroad have been convicted of terrorism-related crimes in the United States” since 2001. The phrase “terrorism-related” is intentionally broad and can include providing “material support” by sending money abroad. Without specific examples, we have no idea exactly how terrorism-related any of these individual convictions are.

To sum it all up then, the Trump administration was battered in the courts for failing to connect the travel ban to any actual terror attacks originating in these specific countries. Its response is to point to two cases that have no bearing on that claim and to assert that hundreds of other unnamed cases pertaining to refugees from unknown countries are all the proof we need that this new ban is both urgent and targeted. If the many courts that declined to accept the “trust us” defense in litigation last month are any indication, a new executive order rooted in the sound illogic of “trust us, plus other stuff!” also seems unlikely to persuade.