Starting last month, Slate began a series of monthly dialogues between two of the nation’s most esteemed jurists, Richard A. Posner and Jed S. Rakoff. These conversations will be moderated by Joel Cohen, author of the book Blindfolds Off: Judges on How They Decide. The subject of their first conversation was how much deference the president should be given to make Supreme Court selections that comport with his ideology. This month’s conversation is about when and how judges should bring their own personal convictions into the courtroom.

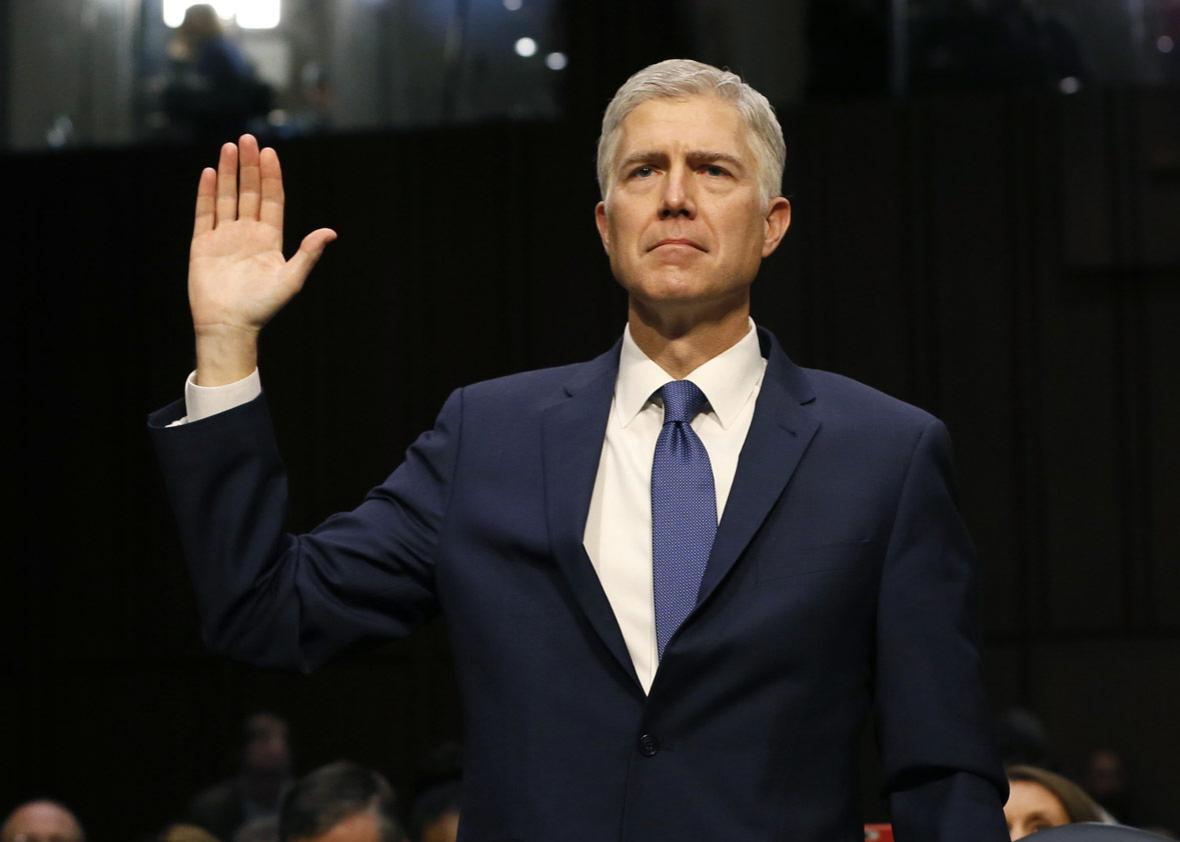

Joel Cohen: Judge Posner, during Judge Gorsuch’s confirmation hearing last week, Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar paraphrased you in questioning the Supreme Court nominee. According to Klobuchar, you have previously said that it is “naïve to think that judges believe only in the legal technicalities of their argument.” Rather, as she put it, “judges consult with their own moral convictions to produce the best results for society.” Judge Gorsuch disagreed.

I know that as a federal judge you can’t comment on confirmation proceedings. So let’s put aside how Judge Gorsuch responded. Do you believe that judges do, and should, consult with their moral convictions to get the best results for society?

Judge Richard A. Posner: I wouldn’t consider it proper for a judge in a case to invoke or rely on idiosyncratic moral convictions, but I think it proper for a judge to rely on the general, broadly held moral convictions of his society, provided those convictions are both pertinent to the case at hand and not overridden by other considerations that judges have to take account of.

Judge Jed S. Rakoff: As Judge Posner’s statement suggests, it is a matter of degree. Every judge sooner or later feels obliged to make a decision he regards as “unfair” but mandated by the law. If judges are to fulfill their basic duty to apply the law impartially, it could hardly be otherwise. But there are also many cases where a judge has discretion to go either way, and a judge’s moral convictions will sometimes influence that decision. Again, it could hardly be otherwise; it is part of what any judge sees as “doing justice.” The danger, of course, is that judges, like other human beings, sometimes mistake policy issues for moral issues, and a wise judge will be on guard against this danger.

Cohen: Gentlemen, I’m somewhat confused. Much of the public and many members of the U.S. Senate object to “activist” judges—meaning here, those who employ their robes to promote social policies that they individually would like to see enacted. And “activists” clearly exist on both sides of the political divide. Respectfully, it seems to me that you’re both using language that promotes the principle—maybe the received wisdom—that judges shouldn’t consult their own moral convictions but still allows them to do so when they really want to. Not so?

Posner: I distinguish between personal moral convictions and moral convictions that a judge shares with the rest of the society, or at least with a substantial share of the rest of the society, or that he reasonably believes the rest of the society or a large fraction of the rest can be persuaded to share. Even so, he or she must be careful to make sure that relying on those convictions to decide a case would not run afoul of an authoritative legal principle or rule or decision.

Rakoff: I think what confuses you, Joel, is that Judge Posner and I are in more or less complete agreement on this. (Sorry about that!) What we are both saying is that, in most cases, a judge’s job is to decide a case on the basis of reason and practice rather than by resorting to the judge’s personal sense of morality, which may often amount to little more than ideological preferences.

But there are occasional cases where a “technically correct” ruling would seemingly result in a decision so wildly at odds with prevailing moral principles that a judge should feel compelled to re-examine how that could be. After all, much of the law is, in a sense, applied morality, so if a particular result seems repugnant to basic and widely shared moral principles, a judge has to ask whether a big mistake has been made that needs to be corrected before the law loses its moral force. If that sounds to you like “it depends,” well, that is what judging is all about.

Cohen: So in a case which, to many, may implicate a moral issue—say the death penalty, or same-sex marriage, or a travel ban (if clearly an invidious discrimination against members of a particular religion)—would it be proper for the judge to consult his or her idiosyncratic moral leanings in deciding the case?

Posner: As I said earlier, it isn’t proper for a judge to decide a case (or vote to decide a case) on the basis of an idiosyncratic moral belief, such as that monkeys should have the rights of people, or that prison sentences should be limited to given years regardless of the crime. What seems to be both defensible and common is for a judge to be influenced in voting in a case by his or her common sense, and what we call common sense is a medley of practical considerations (such as cost and other economic consequences) and moral or ethical ones, such as revulsion at executing children who commit murders, provided both the practical and the moral/ethical considerations are not idiosyncratic to the judge invoking them, but widely shared by the people in his or her contemporary society.

Rakoff: Distinguishing between “idiosyncratic moral leanings” and “widely shared moral beliefs” may itself be a complicated question in certain circumstances. When I am picking a death penalty jury, I am required by law to exclude those potential jurors who believe that society should never impose the death penalty because “thou shalt not kill” and those who believe that the death penalty is always appropriate for anyone convicted of murder because “an eye for an eye.” But while the Supreme Court has not adopted either of these views, it has nevertheless recognized that the death penalty presents moral questions that must be taken into account in deciding what is required for death penalty statutes to pass constitutional muster, because, in the court’s words, “death is different.”

The point is that a judge is not a priest or a rabbi; his or her job is to say what the law is, not what it ought to be (though off the bench, a judge is free, and even encouraged, to suggest improvements in the law). But in so deciding, a judge should not, and often cannot blind himself to the moral implications of deciding one way or the other, and in such circumstances, it is appropriate for the judge to hesitate long and hard before embracing a conclusion that seems contrary to everyday moral principles.

As for myself, the only “idiosyncratic moral principle” that I fully embrace is that a column should not go on for as long as this one has.