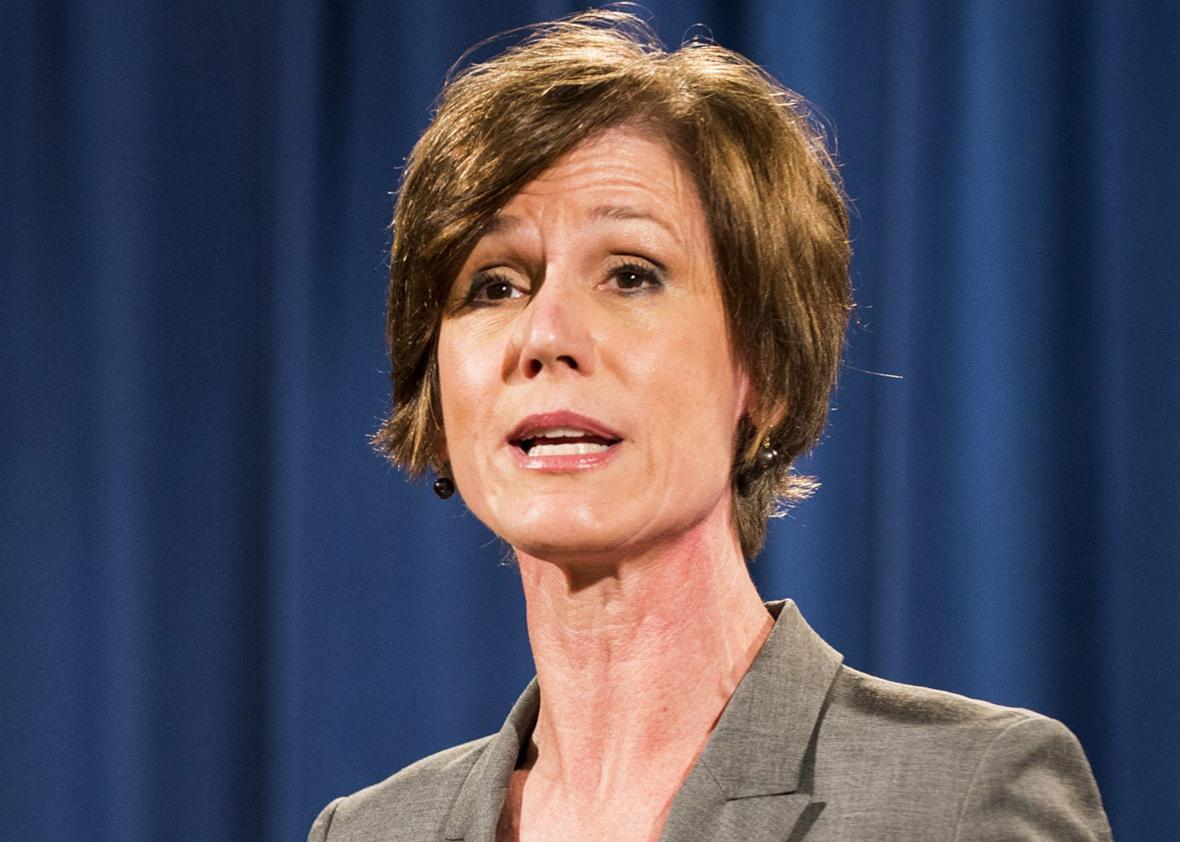

On Tuesday morning, the Washington Post reported that the Trump administration had tried to muzzle Sally Yates, a leader in the Obama-era Department of Justice who had been invited to testify before the House Intelligence Committee about Russian interference in the 2016 election. Earlier this month, according to the Post, the Trump administration sought to prevent Yates from telling the committee everything she knew, informing Yates’ lawyer that any conversations she’d had with White House officials while working in the DOJ were likely protected by executive privilege. Four days before the Post story came out, the hearing at which Yates was scheduled to testify had been abruptly canceled by Republican committee Chairman Devin Nunes.

At the Tuesday afternoon White House press briefing, Trump spokesman Sean Spicer said the Post story was “100 percent false.” The Trump administration had done nothing to discourage Yates from testifying, Spicer insisted, and had in fact given Yates tacit permission to say whatever she wanted. By this time the Post story had already taken flight, moving journalists to pepper Nunes with questions about whether his decision to cancel the hearing was related to the machinations revealed in the Post story, and prompting commentators to tweet the link with annotations like “welp” and “big” and “wait wait wait.” Historian Simon Schama called the situation “already beyond Watergate.”

Who is right? What actually happened between Yates and the Trump administration, and is it fair to conclude that the White House was involved in the cancelation of the hearing? The honest answer, at this point, is that the Post piece raises a lot of questions without providing any concrete answers.

There is plenty of reason for the Trump camp to be wary of Yates, a 27-year veteran of the Justice Department who was fired as acting attorney general after instructing the attorneys on her staff not to defend the president’s first immigration ban in court. Before her ouster, Yates had played a consequential role in the Trump-Russia scandal: On Jan. 26, when she was still leading the DOJ, Yates informed Trump’s White House counsel that then–National Security Adviser Michael Flynn hadn’t been truthful about the content of his conversations with the Russian ambassador to the United States. Flynn resigned under pressure about two weeks later, but only after the Post reported on Yates’ conversation with the White House counsel. One of the big questions going into the scheduled House Intelligence Committee hearing was why the administration had waited so long to act on the revelation Yates had brought to them.

The Post story was based primarily on a set of letters to and from Yates’ lawyer, David O’Neil. The Post’s Devlin Barrett and Adam Entous reported that the letters indicated the Justice Department had notified Yates that “the administration considers her possible testimony—including on the ouster of former national security adviser Michael Flynn for his contacts with the Russian ambassador—to be off-limits in a congressional hearing because the topics are covered by attorney-client privilege or the presidential communication privilege.”

The O’Neil letters added context to the cancelation of the scheduled intelligence committee hearing, implying Nunes had made the decision to call it off after administration officials realized they wouldn’t be able to block Yates from testifying freely. In the Post story, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Adam Schiff, suggested it was possible that “the White House’s desire to avoid a public claim of executive privilege” might have “contributed to the decision” to cancel the hearing. Given pre-existing suspicions that Nunes had been improperly coordinating with the White House on matters related to the Russia investigation, the letters added to the impression that the congressman might have pulled the plug on the hearing at the request of the Trump administration.

What exactly does the correspondence between DOJ and Yates’ lawyer reveal? The Post published three key letters in conjunction with its Tuesday story. In the first one, dated Thursday, David O’Neil asks a Justice Department official whether the agency intends to place any constraints on what his client can tell the House Intelligence Committee. According to the letter, the DOJ had communicated to O’Neil at some earlier point that “all information Ms. Yates received or actions she took in her capacity” as a top DOJ official should be considered “client confidences” that she “may not disclose absent written consent of the Department.” In other words, the Trump DOJ had told Yates she needed the agency’s permission to testify about any past DOJ business—a judgment O’Neil describes in his letter as “overbroad, incorrect, and inconsistent with the department’s historical approach to the congressional testimony of current and former officials.”

The second letter the Post published was the DOJ’s response to O’Neil. In this one, dated Friday, a senior DOJ attorney named Scott Schools indicates that the agency does not intend to tell Yates what she can and can’t discuss in her testimony but that the White House might. The letter doesn’t acknowledge or confirm that the DOJ ever took any other position on limiting Yates’ testimony (as O’Neil’s Thursday letter had suggested), but it does warn that any conversations Yates had with White House staff are “likely covered by the presidential communications privilege and possibly the deliberative process privilege.” Therefore, the Schools letter says, if Yates seeks “authorization” to testify about those discussions, she needs to get it from the White House, not the DOJ.

O’Neil evidently took that advice. Later on Friday, he sent a letter to White House Counsel Don McGahn informing him that Yates planned on answering the committee’s questions about the Russia investigation. O’Neil ended by saying that if he didn’t hear back from the White House by 10 a.m. on Monday, he would conclude that the administration would not be asserting executive privilege in connection with Yates’ testimony and that Yates could speak freely about her nonclassified interactions with White House staff. That same day, Friday, it was announced that Nunes had canceled the Yates hearing.

The chain of letters published by the Post raise several questions. First, where did David O’Neil get the idea, expressed in his Thursday letter, that the DOJ had demanded approval power over what Yates told the House Intelligence Committee? As of this moment, O’Neil is the only source for this claim. Second, if O’Neil’s description of the DOJ’s position in that letter was accurate, why had the DOJ seemingly reversed its stance by the time Schools wrote back to O’Neil the following day? Third, was the decision by Nunes to cancel the hearing in any way related to the letter O’Neil sent to the White House counsel’s office?

At his Tuesday briefing, Sean Spicer declared unequivocally that the Trump administration had not tried to stop Yates from testifying. On the contrary, he said, the White House counsel’s office had tacitly given her its blessing to speak freely by not responding to O’Neil’s Friday letter. What Spicer left out was that the White House barely had a chance to respond to the letter, given that the hearing was canceled on the very same day it was sent.

O’Neil, for his part, declined to be interviewed for the Post story. He also didn’t respond when I emailed him asking for clarification on what DOJ officials told him, and why they might have changed their minds between Thursday and Friday about how much authority they wanted to assert over Yates’ testimony. Sarah Isgur Flores, a spokeswoman for the DOJ, declined to comment to me as well.

Despite the lack of clarity on what the Post story reveals or doesn’t reveal, the newspaper’s reporting will have consequences. As Nunes bats away calls to recuse himself from the Russia investigation, it stands to reason that other members of the House Intelligence Committee will feel increasing pressure to bring Yates in to testify as soon as possible. Even Spicer, at his briefing Tuesday, felt compelled to perform that sentiment, saying he looked forward to Yates’ appearance in front of the committee. Now that the public has reason to think Trump’s DOJ tried to have Yates silenced, it has become much less likely that Spicer—and the rest of us—will be denied the pleasure of hearing what she has to say.