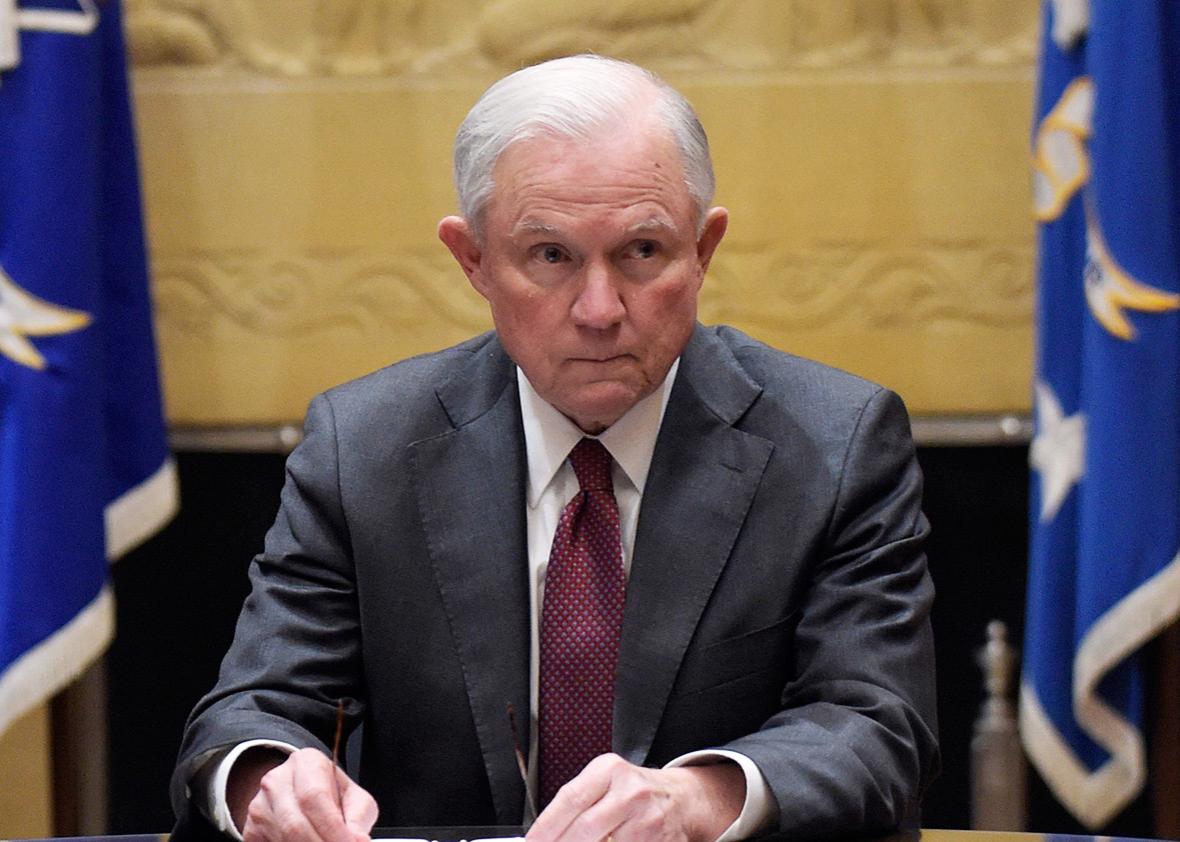

The American Civil Liberties Union wants Attorney General Jeff Sessions investigated for perjury. Rep. Keith Ellison, the deputy chairman of the Democratic National Committee, suggested Thursday that he does as well, tweeting that perjury is “a felony and may be punishable by prison for up to five years.” The Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee have submitted a formal letter to FBI Director James Comey saying the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for Washington, D.C., should open a criminal investigation into whether Sessions broke the law.

The basis for these claims is the allegation that, during his January confirmation hearing, Sessions falsely told Congress that he “did not have communications with the Russians” during the 2016 presidential campaign, when in fact he did. It also stems from a written statement Sessions submitted in response to a question from Sen. Patrick Leahy, about whether he ever discussed the 2016 election with any Russian officials. Sessions’ answer to that question was just one word: “No.” He implicitly defended that response at a press conference Thursday by saying he didn’t remember talking to the ambassador about the campaign.

If that all sounds like an open-and-shut case of lying under oath, some cooling of the jets is in order. That’s because perjury, along with the handful of other statutes that criminalize dishonest statements made to Congress, requires prosecutors to prove that a defendant “willfully” made a statement he knew to be untrue. In other words, Sessions would’ve had to lie on purpose, not simply utter a falsehood by accident. A plausible case for perjury can be mounted only if there is no room to believe that Sessions thought he was being honest.

How do you determine the intent behind a statement? Given that we can’t dive inside Sessions’ brain or peer into his heart, we must resign ourselves to circumstantial evidence. Analyzing the wording of Sessions’ response to Sen. Al Franken’s query about Russia, in other words, is not enough. While it’s important to ask, as a foundational matter, whether Sessions left himself any room for plausible deniability—whether there’s any way to construe his statement as factually accurate—his answer in isolation is not sufficient to determine whether an act of perjury has taken place. Instead of drilling into Sessions’ choice of words, legal experts told me, we must examine the broader context surrounding both Franken’s question and the future AG’s response.

There are at least two important bits of context to consider. First, Franken asked Sessions about a specific CNN report that had come out during the confirmation hearings. In fact, it was published just a little more than an hour before Franken asked Sessions about it, meaning the Minnesota senator had to summarize its findings before prompting Sessions to respond. Here’s the complete transcript:

Franken: CNN just published a story alleging that the intelligence community provided documents to the president-elect last week that included information that “Russian operatives claimed to have compromising personal and financial information about Mr. Trump.” These documents also allegedly say, “There was a continuing exchange of information during the campaign between Trump’s surrogates and intermediaries for the Russian government.”

Now, again, I’m telling you this as it’s coming out, so you know. But if it’s true, it’s obviously extremely serious, and if there is any evidence that anyone affiliated with the Trump campaign communicated with the Russian government in the course of this campaign, what will you do?”

Sessions: Sen. Franken, I’m not aware of any of those activities. I have been called a surrogate at a time or two in that campaign and I didn’t have—did not have communications with the Russians, and I’m unable to comment on it.

At his press conference Thursday, Sessions tried to give a window onto his state of mind in those moments. The part of Franken’s question he focused on, Sessions said, was the CNN scoop about a “continuing exchange of information during the campaign between Trump’s surrogates and intermediaries for the Russian government.”

“It got my attention,” Sessions said. “And that is the question I responded to.” A few minutes later, he elaborated: “I was taken aback a little bit about this brand-new information, this allegation that a surrogate—and I had been called a surrogate for Donald Trump—had been meeting continuously with Russian officials. It struck me very hard, and that’s what I focused my answer on.”

Reading between the lines a bit, Sessions seems to be saying that the shock of hearing about this bombshell CNN report caused him to intuit that Franken wanted to know if he was one of the surrogates in question. Because Sessions’ conversations with the Russian ambassador, in his mind, weren’t part of a “continuing exchange of information,” it didn’t occur to him to mention them.

The notion that Sessions was simply caught up in the moment and speaking imprecisely—in his press conference Thursday, he conceded that he should have “slowed down” before answering Franken’s question—seems like the definition of a lame excuse. But it’s also just plausible enough to stave off a perjury charge, which not even the most hard-charging federal prosecutor would bring against a sitting attorney general if he or she wasn’t absolutely sure it was a winning case.

As many observers have noted, one curious aspect of the back and forth between Franken and Sessions is that Franken was not asking Sessions if he personally had contact with any Russians during the campaign. He just wanted to know what he’d do if confronted with evidence that other members of the Trump team had. It’s peculiar that Sessions, unprompted, rushed to deny any personal involvement in that hypothetical scandal, but it arguably lends some credence to the “taken aback” defense: Sessions was flustered by this report he was just hearing about for the first time, and he was eager to establish that his hands were clean.

But there’s another way to look at the mismatch between Franken’s question and Sessions’ answer. What if Sessions went into the hearing intending to volunteer his own innocence, and followed through on that plan as soon as he saw an opportunity? This is, obviously, speculation, but when you consider that Sessions was almost certainly armed to the teeth with carefully calibrated answers when he went into the hearing, it potentially bolsters the case that his statement to Franken was a deliberate and strategic lie. As Jeff Berman, a former staffer to Sen. Chuck Schumer, wrote on Twitter on Thursday, it is exceedingly hard to imagine that Sessions didn’t meticulously think through the answers he would give at the hearing—especially on sensitive topics like Russia, which was sure to come up given how big of a story it had been since the election.

“This is not a mayor testifying at a hearing on an urban renewal initiative which she knows cold—this is someone preparing for a confirmation hearing for one of the highest offices in the land,” Berman said by phone Thursday. “It would be jaw-dropping if they had not had multiple rounds of preparation with mock hearings, with staffers playing the role of senators, asking questions that are likely to come up, and working on answers.”

This is perhaps the best case for a perjury charge: Sessions had to have known he would be asked about Russia, which means he answered the way he did on purpose. And if he answered the way he did on purpose, that means he deliberately didn’t mention his conversations with the Russian ambassador.

And yet even this line of argument would be unlikely to fly in an actual courtroom. According to Duke University School of Law professor Lisa Kern Griffin, who specializes in “the criminalization of dishonesty in legal institutions and the political process,” witnesses are routinely coached by their lawyers, and yet falsehoods uttered on the stand don’t typically lead to perjury charges on that basis. While it’s possible that Sessions, a Cabinet appointee testifying before Congress, would be held to a different standard and would be seen as a “sufficiently sophisticated actor that the facts would play out differently in that respect,” Griffin said the likelihood of perjury charges being brought against him remains infinitesimally small. There’s just too much about his exchange with Franken that’s up for debate.

“The perjury statute is so exacting that this strikes me as a very difficult case,” said Griffin, “mostly because what he did end up saying is subject to a certain amount of interpretation, and that’s usually the death knell for a perjury charge.” It’s not an obstacle that is frequently overcome. According to a 2007 law review paper called “The Perjury Paradox,” (hat tip: Vox), “Almost no one is prosecuted for lying to Congress; in fact, only six people have been convicted of perjury or related charges in relation to Congress in the last sixty years.”

Securing a criminal charge against Sessions, though, would hardly be the only goal of launching an independent investigation into his conversations with the Russian ambassador. As ACLU political director Faiz Shakir explained to me, such an investigation could clarify many unanswered questions about the Trump team’s ties with Russia. “There’s a good number of groups that are just calling for Sessions’ resignation, and that’s totally understandable,” Shakir said. “We are much more in the position of, ‘Let’s get some facts.’ ”