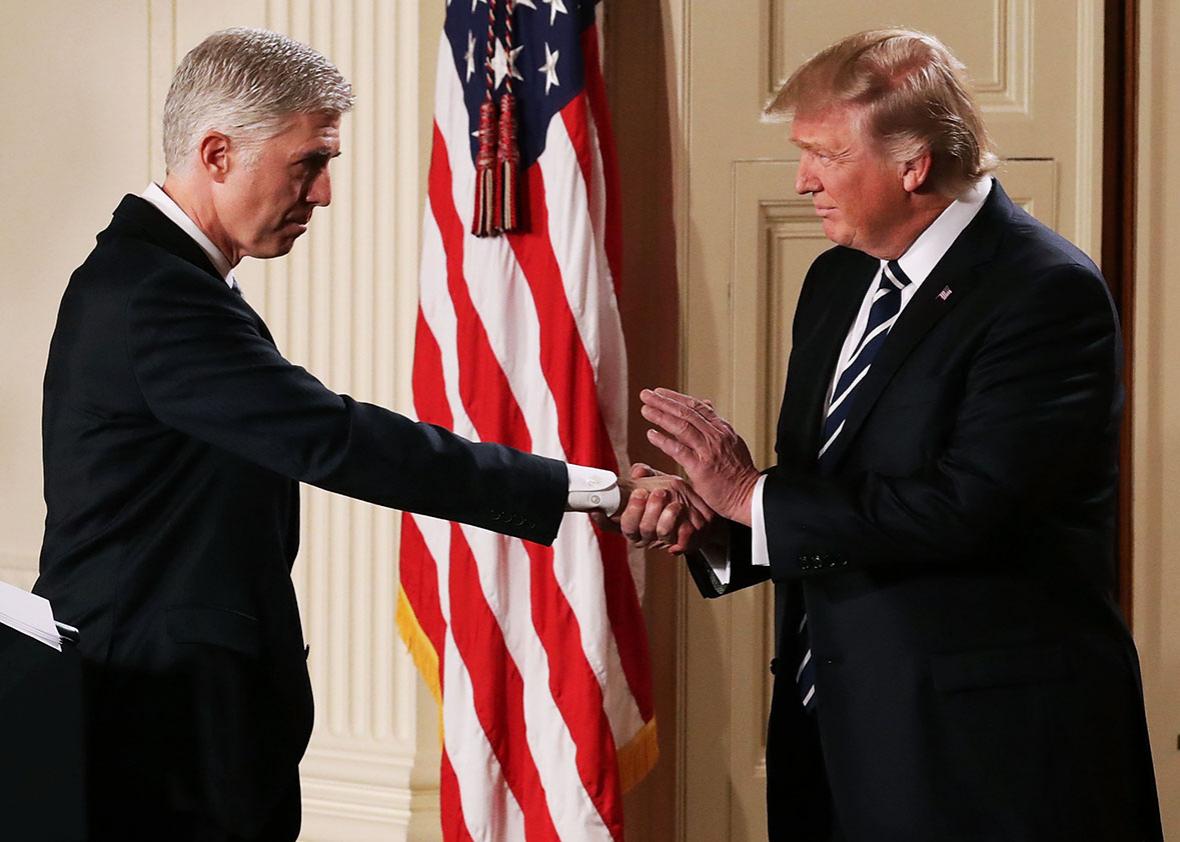

Given the dramatic and divisive start to Donald Trump’s president, Tuesday’s Supreme Court nomination announcement raises an interesting question: How does Trump’s nomination of Neil Gorsuch heal or inflame America’s deep divisions? Here’s a quick scorecard.

On the divisions within the Republican Party, between Trump and the establishment. Trump picked from the establishment’s wish list, as promised. No prominent Republican officeholder has breathed a word of opposition.

On the divisions between coastal elites and the heartland. Gorsuch was educated at two of America’s finest coastal academies (Columbia University and Harvard Law School) but hails from the Rockies. Every single current justice went to Harvard or Yale Law, and Gorsuch is no different in this respect; but if confirmed, he would be refreshingly unique insofar as his home is not on or near an ocean.

On religious divisions. He diversifies but is also a throwback. “Making America Great Again” was in part a subliminal reaction to the utter absence of WASPs at the top of all three branches of government. In 2014, none of the nine justices was a Protestant (there were six Catholics and three Jews); and Congress was formally headed by Vice President Joe Biden (a Catholic), House Speaker John Boehner (another Catholic), and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (a Mormon). The only mainstream Protestant in the citadel’s top floor had the middle name “Hussein.” Today, both president and vice president are WASPs from mainstream denominations; so is Senate Leader Mitch McConnell, and Gorsuch would be the court’s first Protestant in seven years.

On the divide between judges and politicos. Like all the current court members, Gorsuch is highly judicialized. In 1954, the bench that decided Brown v. Board contained only one justice who had been a federal judge before reaching the Supreme Court. Most of the justices in Brown were former pols—governors, senators, Cabinet chiefs. By contrast, all of the current justices except Elena Kagan were sitting federal appellate judges when appointed; most served as judicial law clerks early in their careers; and two of the most recent appointees (John Roberts and Kagan) did multiple clerkships. Gorsuch outdoes them all in this department, having clerked for three judges (including two justices). If confirmed, he will be the first justice to sit alongside a former boss. Roberts succeeded his former boss, William Rehnquist, whereas Gorsuch will overlap with his, Anthony Kennedy. But here too Gorsuch is also a throwback. Although he himself never served in the Cabinet, his mother did. Perhaps this perspective—children learn what they live—may make him more wise to the ways of Washington than, for example, John Paul Stevens, or David Souter, or Sonia Sotomayor, or Kennedy, none of whom came to the court with any experience as a top-level D.C. insider or as a highly accomplished elected politician.

On the divide between Democrats and Republicans and between liberals and conservatives. This is the one area where things start to get sticky. Many Democrats remain irate that Merrick Garland never got a hearing. But even had Garland been heard, there was never a guarantee that he would have been confirmed. After all, the Republicans controlled the Senate. Gorsuch is clearly not the Democrats’ favorite Republican the way that Merrick Garland and Stephen Breyer were the Republicans’ favorite Democrats. He is not the reincarnation of Anthony Kennedy, whom Republican icon Ronald Reagan named in 1987 to placate Democrats after the disastrous Robert Bork nomination came crashing down. But Democrats controlled the Senate back then, and they do not today, so Trump can drive a harder bargain. And unlike some others on Trump’s short list, Gorsuch was unanimously confirmed for his lower-court seat. The first justice for whom he clerked, Byron White, was a Democrat appointed by a Democrat president (JFK) who chose to step down when another Democrat (Clinton) was in the White House. On the other hand, White was in certain ways a conservative Democrat, who dissented in Roe v. Wade and penned the infamous anti-gay ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick. Antonin Scalia (whom Gorsuch has praised to the skies) wrote another famously anti-gay opinion (in dissent) in Romer v. Evans—a case from Gorsuch’s home state of Colorado. The majestic majority opinion was written by none other than Anthony Kennedy. Don’t be surprised if these two cases, featuring three Gorsuch mentors, loom especially large in the confirmation hearings ahead.

When pressed, will Gorsuch fudge or try to resist the tide of history on gay rights, à la White and Scalia; will he blandly acknowledge that same-sex rights are a fait accompli; or will he affirmatively embrace Kennedy’s bottom line by invoking originalist scholarship supportive of gay rights, by scholars such as Steven Calabresi (co-founder of the Federalist Society) and yours truly? Stay tuned. A great constitutional seminar awaits.