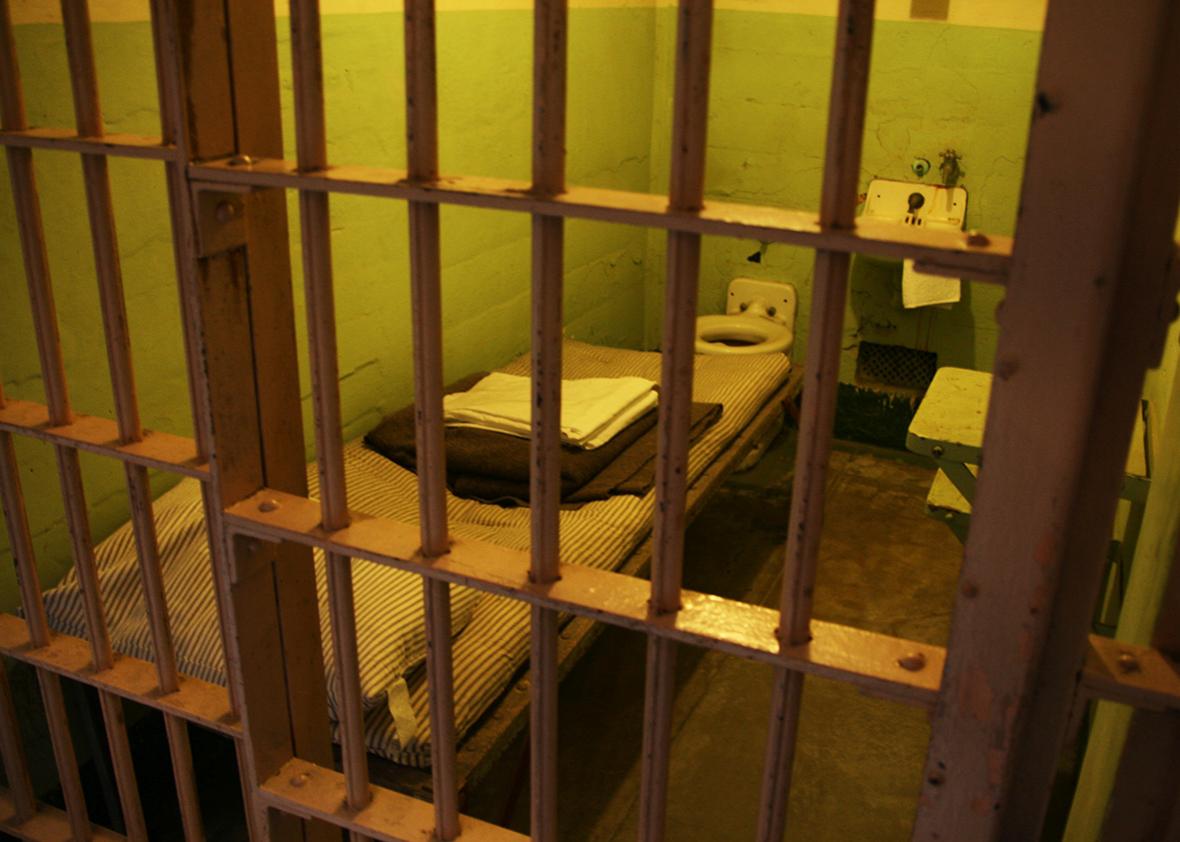

Shawn T. Walker spent 20 years in a windowless cell measuring 7 by 12 feet. He was allowed to leave that cell five times a week to spend two-hour intervals in a restricted area known as the “dog cage.” Before entering the dog cage, Walker was required to undergo a strip search—including a body cavity search. To avoid these intrusions, Walker did not leave his cell for nearly seven years. He ate his meals alone in his cell, where he was constantly inundated by the sounds of other inmates in solitary confinement. Like virtually everyone subject to solitary, Walker developed severe mental disorders including insomnia, acute emotional distress, and uncontrollable body tremors.

Walker’s first 14 years in solitary were unavoidable: Pennsylvania placed him on death row for committing first-degree murder, and in Pennsylvania, death row is solitary confinement. But after 14 years, his capital sentence was vacated. Walker was no longer awaiting execution—yet the state kept him locked in solitary, without any clear explanation as to why, for six more years. Only after a court formally converted Walker’s sentence to life imprisonment was he removed from solitary and placed in the general population. Eventually, Walker sued, alleging that his six extra years in solitary violated his constitutional rights.

On Thursday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit agreed with Walker in a broad ruling that strictly limits the use of solitary in the three states within the circuit: Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. The decision marks a considerable victory for opponents of solitary who argue that prisons routinely abuse the practice in violation of the U.S. Constitution. This week’s ruling contributes to a growing consensus among federal courts that the judiciary must curb solitary confinement—a consensus likely to be affirmed by the Supreme Court in the near future.

The 3rd Circuit considered Walker’s suit along with that of Craig Williams, another former death-row inmate who remained in solitary after his capital sentence was vacated. Unfortunately for Walker and Williams, the court concluded that prison officials had not violated a “clearly established right” by keeping both men in solitary for no clear reason. That means the officials can’t be held liable for damages.

The good news is that the court has now established such a right, and all prison officials will be held to the new standard moving forward. Under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause, the court explained, inmates have “a liberty interest” in not being subjected to solitary confinement “absent procedural protections that ensured the confinement was appropriate.” These “procedural protections” must “ensure that continuing this level of deprivation is required for penological purposes, and is not reflexively imposed without individualized justification.”

Put differently, the state may not keep inmates in solitary indefinitely; rather, it must have “individualized justification” for keeping them confined, and must implement formal procedures “to determine if the level of dangerousness justifies the deprivations imposed.” Although the case at hand involves death-row inmates whose capital sentences were vacated, the ruling appears to apply to all inmates in solitary. The upshot is that prisons within the 3rd Circuit are now constitutionally obligated to regularly assess whether an inmate in solitary who is not serving a capital sentence is dangerous enough to keep in solitary. And if a prison holds an inmate in solitary “without individualized justification,” it opens itself up to legal liability.

What’s most remarkable about the 3rd Circuit’s decision isn’t its holding. Rather, it is its deep skepticism about the constitutionality of solitary as it is routinely applied in the United States. While the court decided this case on due process grounds, its ruling comes close to arguing that solitary may often violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments.” Quoting from “a comprehensive meta-analysis of the existing literature on solitary confinement within and beyond the criminal justice setting,” the court noted that “the empirical record compels an unmistakable conclusion: this experience is psychologically painful, can be traumatic and harmful, and puts many of those who have been subjected to it at risk of long-term … damage.”

It continued:

The researchers found that virtually everyone exposed to [solitary] conditions is affected in some way. They further explained that “[t]here is not a single study of solitary confinement wherein non-voluntary confinement that lasted for longer than 10 days failed to result in negative psychological effects.” …

Anxiety and panic are common side effects. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis, hallucinations, paranoia, claustrophobia, and suicidal ideation are also frequent results. … In the absence of interaction with others, an individual’s very identity is at risk of disintegration.

Physical harm can also result. Studies have documented high rates of suicide and self-mutilation amongst inmates who have been subjected to solitary confinement. These behaviors are believed to be maladaptive mechanisms for dealing with the psychological suffering that comes from isolation. In addition, the lack of opportunity for free movement is associated with more general physical deterioration. The constellations of symptoms include dangerous weight loss, hypertension, and heart abnormalities, as well as the aggravation of pre-existing medical problems.

The court then cited multiple rulings by circuit and district courts limiting the application of solitary confinement due to its horrific effects on inmates. “As we have explained,” the court wrote, “scientific research and the evolving jurisprudence has made the harms of solitary confinement clear: Mental well-being and one’s sense of self are at risk. We can think of few values more worthy of constitutional protection than these core facets of human dignity.” Therefore, in “our ruling today, we now explicitly add our jurisprudential voice to this growing chorus” of judicial voices questioning the constitutionality of routine solitary for non-death row inmates.

As the 3rd Circuit is surely aware, this chorus has a conductor: Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy. In 2015, Kennedy wrote a concurring opinion sharply criticizing solitary confinement as inhumane and barbaric. In it, he all but telegraphed his desire for opponents of solitary confinement to bring a case to the Supreme Court that will allow justices to limit its use. A landmark decision curbing solitary will be easier to justify if the court can point to an emerging consensus against the practice in the lower courts. The 3rd Circuit just nudged this consensus in the right direction. A Supreme Court ruling cannot be far behind.