On Sunday, Mohamed Jeran and his family left Djibouti, where they’d been stranded for two years. The Jerans’ flight took them to Istanbul, then on to New York City, where they were reunited with Mohamed’s Yemeni American father and two of his brothers. The fact that the Yemeni family had been allowed to fly to the U.S. felt like a small miracle. Their journey followed an excruciating week in which American and international authorities enforced Donald Trump’s executive order on immigration, then declined to abide by multiple court orders that were supposed to grant people like the Jerans passage into the country.

It was against this backdrop of turmoil that Mohamed, his wife, Hanan; their 7-year-old, Amjad; and around 30 other Yemeni refugees made the nearly 30-hour voyage from Djibouti to John F. Kennedy International Airport earlier this week. Mohamed, who is 30, says he spent the entire trip in fear that someone—an airline representative, an agent from Customs and Border Protection, some heretofore unknown authority figure—would tell him his visa was not valid. About seven hours into the flight to JFK, he realized he’d made a careless mistake. Instead of packing the original copy of an important visa form in his carry-on luggage, he had left it in his checked bag, and therefore would not be able to produce it at customs. A paralegal traveling with the family did have a photograph of the form on her phone, but there was no guarantee that would pass muster. And so, for hours, Mohamed lived with the nauseating knowledge that this one tiny error could cost him and his family their lives in America.

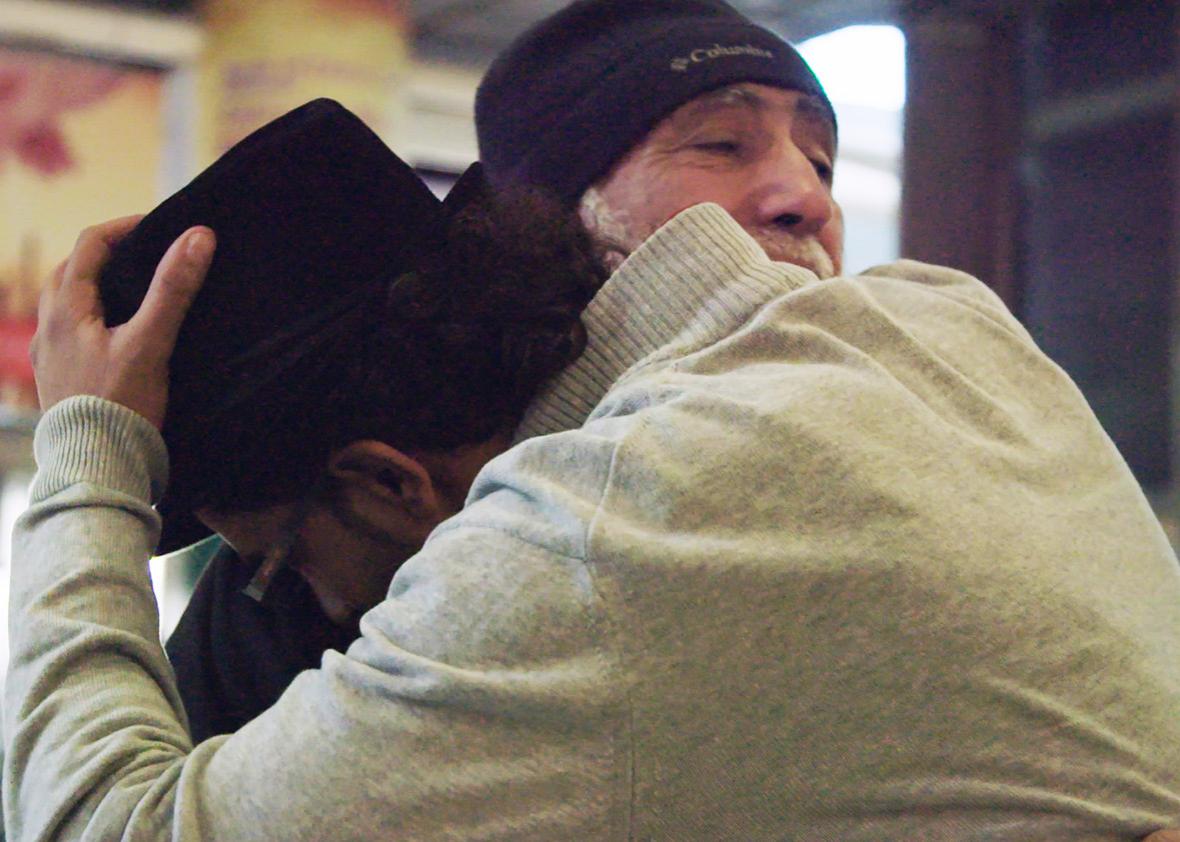

The Jerans were supposed to land at JFK around 11:30 a.m. on Tuesday. In the arrivals gate in Terminal 1, Mohamed’s brother Abrahim and father Mosleh—a man in his 70s who moved to the U.S. about 20 years ago—stood waiting alongside Linda Amrou, a lawyer from the firm that had facilitated the Jerans’ escape from Djibouti. The firm, Goldberg & Associates, is run by Julie Goldberg, an immigration lawyer who opened a practice in Djibouti after Yemenis started pouring into the country to flee from the civil war that began in 2015. Since then, Goldberg—who filed one of the federal lawsuits that resulted in a temporary injunction blocking part of the immigration ban—has helped hundreds of Yemenis find their way to America. But the Jerans have been a special case for her: Mohamed’s father was one of Goldberg’s first-ever clients, and Mohamed had worked closely with her in Djibouti as a translator and an assistant. Mohamed’s brother Abrahim worked in Goldberg’s New York office.

“When I first opened my office and I knew nobody in New York and I fixed [Mosleh’s] case, he would bring me lunch all the time,” Goldberg said last week from Djibouti, during a period when the family was caught in a nightmarish legal limbo. “He’s the sweetest old man. … He was like, ‘You work too much, you have to eat.’ ” When she found out Mosleh’s family was stuck in Djibouti, she traveled there to try to help. When she realized the Jeran family would be stranded there for longer than expected, she got a home in Djibouti and put them up.

At JFK, Mosleh, dressed in a snug winter coat and hat, shifted his weight and smiled tentatively as he waited for his son, daughter-in-law, and grandson to walk through the security gate. In an interview, he recalled the pain of finding out that Mohamed’s student visa—the one he’d waited on for two years and that would have allowed his wife and child to accompany him to the U.S.—was suddenly useless because of Trump’s new rules.

“When I heard this message, I thought, ‘Nobody coming,’ ” he said. “Nobody could believe it. That this order would, in one day, in one night—make everybody get closed? This was coming like thunder. Thunder and lightning.”

It was only when U.S. District Judge James Robart issued a sweeping order on Friday, effectively forcing the Department of Homeland Security to suspend Trump’s travel ban, that Mosleh felt relief. (Prior to Robart’s order, airlines and administration officials had either ignored previous rulings or evaded them by way of dubious loopholes. A temporary restraining order in a Boston court, for instance, should have allowed the Jeran family to fly into Logan Airport—if only the administration had deigned to obey it.)

Aymann Ismail/Slate

Though Mosleh did not discuss it, there was an undercurrent of sadness to this reunion. Just 10 days before Mohamed’s visa was granted, his youngest son, Ashraf—Mosleh’s grandson—died in Djibouti. The boy was 2 years old. Ashraf’s testicles hadn’t descended after birth, and a doctor had told the family that surgery would be required. Hoping their visa would come soon enough that the surgery could be done in America, where it would be safer, the family decided to wait. But the application process—the normal procedure to get a student visa that was in place before Trump was in office—was taking too long, and at the start of this year they decided they had to go through with the medical procedure in Djibouti.

The boy went into cardiac arrest during surgery and died on Jan. 16. After his death, Goldberg says, there was not a proper place to take care of his body. “They washed the body in my kitchen,” she said.

The family was devastated. “He’s like everything for me,” Mohamed said last week, just days after the death of his son. “I don’t live right now since I lost him. He is like my life. Only one who make me whole in this country, Djibouti. … Only one who is making me happy. Now, not.”

On Jan. 26, just 10 days after Ashraf died, Mohamed was issued his student visa. The Jerans were coming to America. “It was the first time I’d seen them smile in two weeks,” Goldberg said. The next day, Trump’s executive order came down. When they arrived at the Djibouti airport, visa in hand, they were turned away.

Aymann Ismail/Slate

For Mosleh, Ashraf’s grandfather, the boy’s passing hurt more profoundly than he could let on. Given his family’s long-delayed arrival to the United States, it felt appropriate to be joyful and to reflect on how badly Trump’s ban misunderstood the people it was affecting. “I say to our president: Please, please, we are here,” Mosleh said. “We are not going anywhere. … This is our country, [and] we are together on the bad people. We are with him on that one. But we are Muslims—we say to the United States, we love this land.”

The plane from Istanbul to JFK landed on schedule. Gradually, the arrivals gate filled up with Yemeni people who were there to welcome their friends and relatives. Eventually, people from Turkish Airlines Flight 3 began to come out, and the mood turned to one of celebration.

But the Jerans did not emerge. While it was too early to worry—plenty of people from the flight had not yet reached the terminal—no one knew exactly what was happening. Was the family being held for a lengthy secondary interview? Had Mohamed been detained, as he’d feared he might be, because his visa form was in his checked luggage?

The idea that something could go wrong at this final stage was harrowing. And yet it was hard to blame the Jerans for thinking there might be another devastating turn in the saga that tore them from their home in Yemen and forced them to look abroad for a new life. That journey began in early 2015, when Houthi rebels took over the Yemeni government and the capital of Sanaa. Mohamed, who lived in Sanaa and was working as a government computer scientist, says the rebels attempted to conscript him into fighting for them. “I told them, give them promise, ‘OK, I will fight, do what you want,’ then I took my family and tried to run away,” Mohamed said.

When Mohamed spoke with his father after the Houthi takeover, Mosleh told him to get to Djibouti, where his family would be safe. In May 2015, Mohamed paid someone $1,700 for access to a boat that would take him, his wife, and their two children across the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait that separates Yemen from Djibouti. They then started the process of applying for a visa to the United States. Mohamed says that when the rebels found out he had fled Yemen rather than staying to fight with them, they bombed his former home.

Djibouti was safer than Sanaa, but it was not a place where the family could stay for the long term. “I don’t want to say anything bad about Djibouti, but for me it’s like hell,” Mohamed says. “The life is not good, everything is expensive, the health there … I lost my son there, because they make a mistake in surgery. So what you want me to call it? I just call it hell.”

Julie Goldberg

Mohamed said last week that he would have been willing to send his family to the United States without him. But that wasn’t an option. It was his visa, so nobody could go to the U.S. if he didn’t go as well.

When Mohamed was trapped in this legal hell, Slate asked him if he had a message for President Trump. He said this:

Why you do that for the Muslims and the Arabic people? Why you want to make a difference between the people? … And I’m going to tell him something: By the way, for two years in Djibouti I was living with an American lady. Never did I ask her, ‘What’s your religion?’ or about that. Nothing. By the way, she is Jewish, I am Muslim, we are living in the same house. So why you make a difference between Muslims and Jews and Christians?

It would be difficult to come up with a better distillation of the First Amendment’s religious protections and the values of inclusion and tolerance that are supposed to be this country’s bedrock. It is striking that this expression of America’s cherished values came from a member of a group that President Trump recently described as “potential terrorists and others that do not have our best interests at heart.”

* * *

At around 12:30 p.m., Mohamed’s brother Abrahim finally spotted a familiar visage. Mohamed was pushing his luggage with a smile on his face. He was walking next to his wife, who was dressed in a niqab, and their unbearably beautiful son. The visa had done its job. There had been no problems. They were here. After about 15 minutes of tearful hugging and kissing, the group emerged outside and took in the air around them.

“Right now, I just don’t believe I’m in New York,” Mohamed said, his eyes betraying the dazed condition of a person who has not slept in three days. “Is that true, I’m in New York right now?”

To assure him that it was, indeed, New York, was to confirm that the nightmare of the past 11 days—and the past two years—was truly over. Mohamed said he remembered finding out about Trump’s executive order late on a Friday night, when many of his Yemeni friends in Djibouti began texting him frantically, asking him to use his English skills to translate.

“All the Yemeni, they love [to watch] the news,” he said. “They check it many times, and when they get any news they send it to me. They say, ‘Mohamed, is that true? Is that true?’ ”

The news had stunned him, Mohamed said. “The door of heaven opened, and then the next day it’s closed. I can’t believe it. Finally I get my visa, and [the order] is signed the next day? My luck, it’s really bad.”

Julie Goldberg

He despaired privately while encouraging his family to stay optimistic and wait for their lawyer to sort the situation out. “My feeling was—no chance. No more. But I only think it, I don’t say it to my wife—I only say, ‘Hold on, Julie [Goldberg], she will fix it. Julie will fix it.’ And she did fix it.”

The decision of the judge in Seattle—the one Trump referred to over the weekend as a “so-called judge”—meant the travel ban was temporarily lifted. Goldberg rushed to buy tickets, and before long, the Jerans were on a plane.

As of this writing, Mohamed Jeran is in New York, where he will stay with his father and his brothers in the Bronx and see the city for the first time. Then he, his wife, and their surviving child will relocate to Toledo, Ohio, where he will pursue his master’s degree in computer science.

Before he left the airport, we asked Mohamed if he would come back to New York to be with his father once he earned his degree. He shook his head. “My visa will be done. I will have to go back to Djibouti.”

We’ll have to wait and see what the Trump administration does, and how lawyers and the courts respond, before we know how this family’s story will end. But for now at least, the Jerans—and many others whom our court system rescued last week—will get to call the United States home.