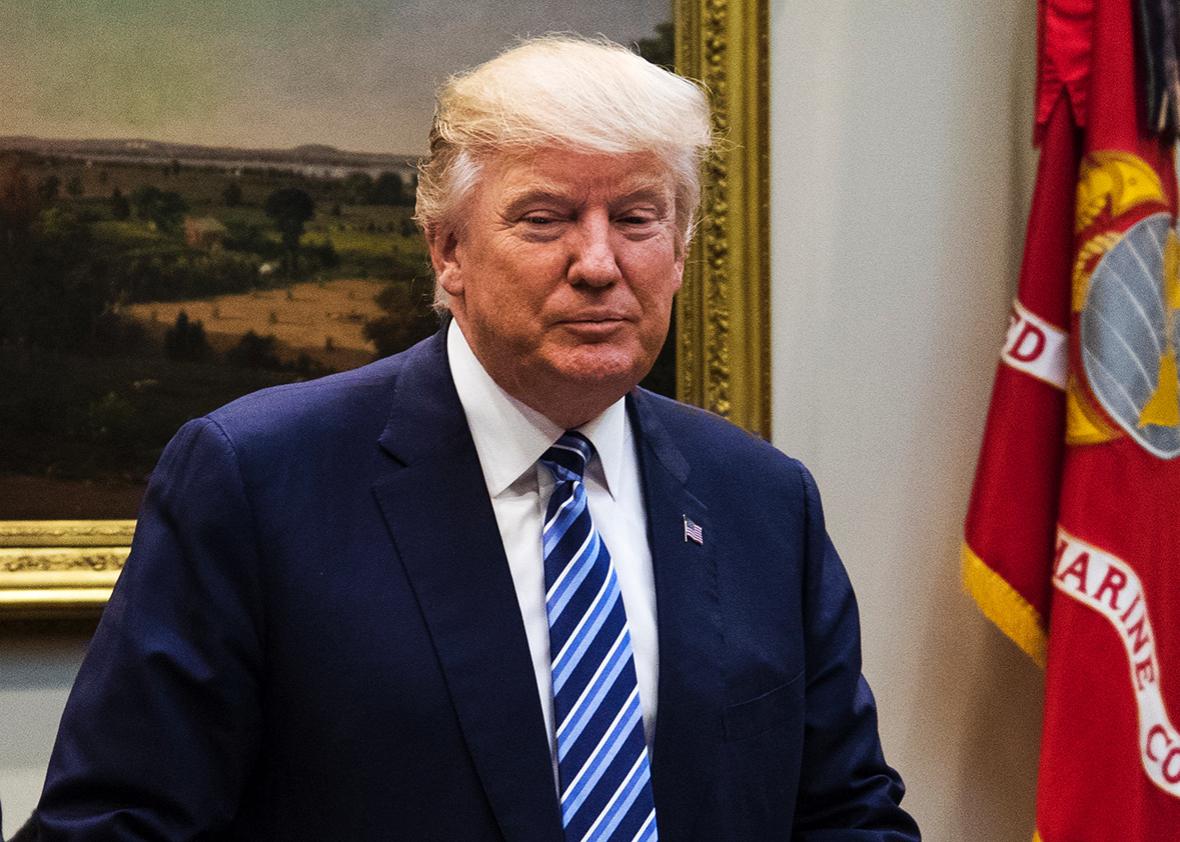

The American deep state—influential career executives in the national security community—has started to push back on President Donald Trump on a number of issues, including immigration, U.S.–Russia policy, and counterterrorism operations. One of the most important may be detention and interrogation, where career military and intelligence officials rejected a draft executive order that would have resurrected the torture regime that existed immediately after 9/11, reflecting campaign promises by President Trump to bring waterboarding (and “much worse”) back into America’s interrogation arsenal.

That they did so should not surprise anyone who has followed the issue over the past decade. Why Trump’s draft order got such a rude welcome, however, deserves attention because it illustrates important changes since 9/11 in U.S. counterterrorism policy and practice. Career professionals in the Defense Department, the CIA, and elsewhere don’t want torture because it doesn’t work, corrodes their integrity, makes it harder to work with allies, and carries enormous risk for strategic blowback. The value of human intelligence has also diminished in relative terms as other American intelligence tools have improved, so there is less incentive for intelligence agencies to want torture in their kits.

This story begins with the detention and interrogation policy that President Trump’s draft order sought to resurrect. Two of President Barack Obama’s three orders relating to torture were to be revoked, and a George W. Bush administration order from 2007 was to be reinstated. The order directed Defense Secretary James Mattis to keep Guantanamo Bay open and use it not just for existing detainees but new ones, too. Trump’s order also directed the military to review its interrogation manual to determine whether it needed more enhanced interrogation tools. And, most notably, the order asked the CIA to consider restarting its “black sites” program for retention, detention, and interrogation of terror suspects, which was shut down by President Bush in late 2006.

The order met stiff opposition from career officials within the Defense Department and the CIA from the moment it left the White House. When a draft leaked, Republican and Democratic national security leaders joined the chorus of dissent. In response, the Trump White House developed a more milquetoast order, keeping Guantanamo’s prison open but jettisoning plans to revive the CIA’s torture program and the military’s more aggressive interrogations, too.

The career professionals in these agencies didn’t push back on the original order because of any political opposition to Trump. The deep state led by these agencies’ career executives, generals, and admirals transcends administrations, and even partisan politics to some extent, despite what Trump may think of their support for him. These professionals pushed back, publicly and privately, because they have learned the hard way that torture is ineffective, unwise, and strategically risky.

Defense and intelligence professionals have learned that torture simply does not work through questioning tens of thousands of detainees since 9/11. The professionals inside the CIA, FBI, Defense, and other agencies have developed an effective arsenal of lawful interrogation techniques that do work—and work particularly well when coupled with other intelligence tools, such as forensic information like fingerprints on the inside of explosive devices. As Secretary Mattis (who oversaw thousands of interrogations during his service in the Marine Corps) reportedly told President Trump, “a pack of cigarettes and a couple of beers” produces better intelligence than torture.

Relatedly, the relative value of human intelligence gained through questioning of any type has declined over the past 15 years. Such intelligence mattered greatly in the few years after 9/11, both for piecing together the parts of al-Qaida and its future plots, and understanding insurgent networks in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the U.S. intelligence community has undergone a renaissance in collection and analysis driven by massive improvements in surveillance technology, computing, big data analysis, and artificial intelligence. Other intelligence tools have also made big leaps forward, such as forensic intelligence collected from cellphones, pocket litter, and improvised explosive devices collected on the battlefield. Human intelligence still plays an important role, but not to the degree it did right after 9/11. Although significant legal questions surround current U.S. surveillance policy, intelligence officials still prefer the relatively clean intelligence produced by these tools to those gathered through detention and interrogation.

Third, it has become clear over the past 15 years that torture, or even lesser included forms of detention and interrogation policy, can be corrosive to the integrity and ethics of national security agencies. Implicit in the statements on torture by then-Gen. David Petraeus and Gen. James Mattis in the counterinsurgency manual they co-authored is a sense that torture degrades the honor of those who practice it. Discipline and integrity are paramount to being effective in war, or clandestine operations in the shadow of war. Mattis, CIA Director Mike Pompeo, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joseph Dunford, and Sen. John McCain understand this better than the president and do not want an executive order that undermines the ethics of their forces or agencies.

Fourth, torture carries huge strategic risks and complications that can make it harder to fight America’s wars. For 15 years, we have depended on allies to fight alongside us in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other theaters of war. Our intelligence agencies have also depended on allies and partners to share information and work together, almost always out of public view. Notwithstanding President Trump’s disparagement of allies and alliances, our national security agencies continue to depend on other countries around the world. These relationships exist because our interests align, but they are strengthened by our shared values.

In the past, America’s torture regime made it very difficult for our allies and partners to work with us or share intelligence with us. The career professionals in Defense, CIA and other agencies know this better than President Trump. They understand all too well that foreign partners are far more likely to work with the U.S. without the antagonism of torture in the mix. Two recent high-profile cases illustrate this—with cooperation flowing from Turkey, Jordan, and Italy precisely because the U.S. provided assurances it would not use Guantanamo for certain detainees, let alone enhanced interrogation, let alone torture.

Fifth, defense and intelligence leaders are reticent about a return to torture because they know they will be left to deal with the repercussions long after President Trump departs office. The Bush administration has long since left office, and so too has the Obama administration. However, the detainees at Guantanamo remain, the legacy of counterterrorism policies more than a decade old. Investigations into detention and interrogation continue as does litigation over liability for torture by the CIA at its black sites. Few, if any, leaders within the Defense Department or CIA want to be left holding the bag yet again.

In many ways, the story of torture is a parable for learning across the national security community since 9/11. In the first months and years after those devastating terror attacks, America lashed out at its enemies. We slowly, and painfully, learned to act more wisely. Our military learned to practice counterinsurgency instead of indiscriminate violence; our intelligence community built strong relationships with allies to target terrorists in the shadows before they could ever harm us. During his campaign, President Trump caricatured this learning as soft and signaled that he wanted a return to more bellicose American national security policy. This cartoonish approach won’t work, and the deep state is our best hope for putting the Trump administration on a better path.