Donald Trump’s surprise victory has left Democrats reeling, in alternating states of shock, anger, fear, and devastation. For many progressives, the most grievous loss is the Supreme Court. The expectation is that President Trump, with the help of a Republican Congress, will install a hard-right majority that will overturn cherished precedents, particularly those guaranteeing fundamental rights to women, minorities, and the LGBTQ community.

One of Trump’s first orders of business will be to replace conservative icon Antonin Scalia, who died in February. Because the Republican-led Senate has refused to hold a vote on Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, the court has limped along with only eight members ever since. During the campaign, Trump released a list of potential nominees for Scalia’s spot. Mainly state and federal judges, their pro-life, pro–Second Amendment, pro–voting rights restrictions, and anti–gay rights bona fides won uniform praise from Republicans.

There is little reason to believe that Trump will deviate from that list; he called it “definitive.” Unlike building a wall and making Mexico pay for it or bringing back manufacturing jobs to the Rust Belt, moving the court unrelentingly rightward is a promise Trump can actually deliver on.

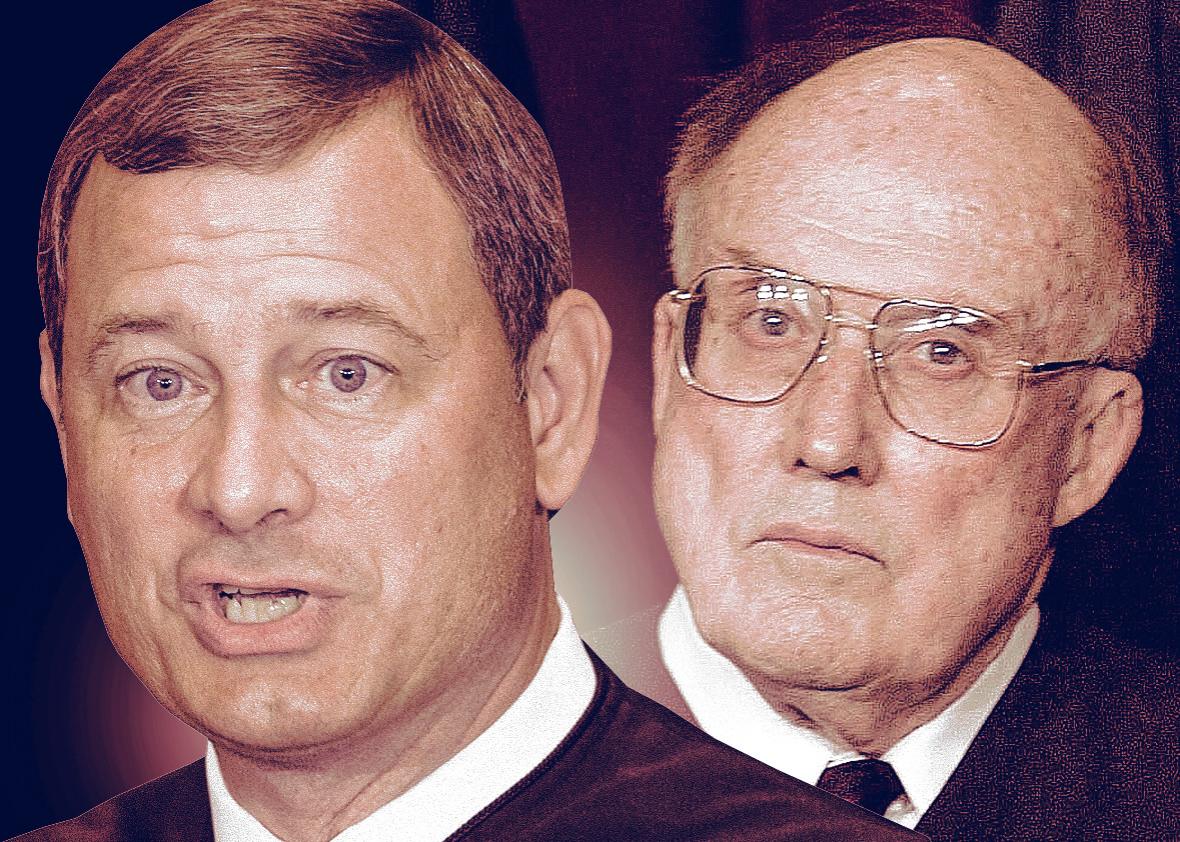

Or can he? Trump’s ability to turn the Supreme Court into a rubber stamp for the right wing rests on two unknowns: whether he will have the opportunity to make a second appointment to replace a member of the court’s liberal wing and, if so, whether Chief Justice John Roberts is willing to march in lockstep with four conservative ideologues.

If Trump makes only a single appointment, we’re back to the status quo: four liberals and four conservatives with Justice Anthony Kennedy as the swing vote. Of course, this is horribly disappointing for progressives. Had Hillary Clinton won and Garland or someone similar been confirmed, the court would have changed dramatically, with the liberals holding a majority for the first time in more than 45 years.

Still, the status quo is far from a disaster. As long as it holds, two of the decisions progressives care most deeply about will remain intact: Roe v. Wade, which in 1973 constitutionalized a woman’s right to abortion, and Obergefell v. Hodges, which in 2015 constitutionalized the right of gay couples to marry.

The problem arises if the next death or retirement comes from the liberal wing or the center of the court. And it well might: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the leader of the liberal voting bloc, is 83; her colleague, Justice Stephen Breyer, is 78. Justice Kennedy, who wrote the Obergefell decision and has consistently voted to uphold Roe, is 80. If Trump installs not one but two Scalia lookalikes, it will be John Roberts, not Anthony Kennedy, who will cast the deciding vote in cases challenging Roe or Obergefell.

Is there any reason to believe that Roberts, like Kennedy, might swing in the liberal direction, particularly when it comes to gay rights and abortion, both of which Roberts staunchly opposes? Most experts scoff at the idea. Erwin Chemerinsky, a renowned constitutional scholar and dean of the University of California–Irvine School of Law says, “Roberts does not follow precedent when he doesn’t agree with it in the areas where he is a true believer. That includes Roe.”

And yet. Roberts is not simply one justice out of nine; he is the leader of a court that will bear his name throughout his tenure. As chief justice, he has a unique responsibility to safeguard the integrity of the third branch of government. If the Supreme Court devolves into an ideological mouthpiece, as overtly political as Congress and the White House, Robert’s decade-long advocacy for judicial restraint and respect for precedent will be read as cant. Roberts himself will be seen as a hypocrite who put his personal preferences above the rule of law. History will view him as a failure.

And John Roberts does not intend to fail. He is keenly aware of his institutional role and he cares deeply about legacy—the court’s and his own. In 2007, when Jeffrey Rosen of the Atlantic asked Roberts to comment on the men who occupied this most rarified of roles before him, he replied, “It’s sobering to think of the seventeen chief justices; certainly a solid majority have been failures.” He went on to explain that these predecessors failed because they were overtly ideological; their members fractious, their opinions splintered and doctrinally unsound. He told Rosen, “I think it’s bad, long-term, if people identify the rule of law with how individual justices vote.”

* * *

Many experts are convinced that Roe and Obergefell will be overturned with the installation of a second Trump pick and the plucking of the right case. Women seeking abortions will have to go to the blue states where they’ll still be allowed, a practical impossibility for many. Some may risk their lives with back-alley abortions. Gay people who are married suddenly won’t be anymore, at least not in red states, their guarantee of equal status wiped away with the stroke of a pen.

There are several reasons to hope that might not happen. In addition to Roberts’ regard for his legacy, there is his self-professed judicial philosophy, somewhat unconventional voting record, and the hard lessons learned from his predecessor-mentor, the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

During Roberts’ confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2005, he famously stated, “My job is to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” The role, Roberts said, was important but also limited by stare decisis—a Latin phrase meaning “to stand by things decided.” He explained, “Judges have to have the humility to recognize that they operate within a system of precedent, shaped by other judges.”

As Roberts later told Rosen, if he began every conference with his colleagues with an “agenda” about how to decide a case, they would dismiss him, and rightly so. Instead, he said, he had worked hard to earn the trust of the other members of the court by not being an ideologue.

Of course, it may be credulous to take Roberts at his word. He has presided over some of the most sweeping and controversial decisions in recent memory, most notably in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which held, in 2010, that corporations have a First Amendment right to spend unlimited amounts of money to elect the candidate of their choice, and Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated, in 2013, a crucial part of the Voting Rights Act empowering the Justice Department to protect the rights of minority voters in states with a history of racial discrimination. Both decisions overturned decades of precedent.

But in 2012, it was Roberts—not Kennedy—who provided the fifth and crucial vote in King v. Burwell to uphold the Affordable Care Act, Obama’s signature legislative achievement, which provides health insurance to millions of people that would otherwise have none. Roberts also voted to reject a similar challenge to a statute expanding Medicaid coverage. He joined with Kennedy and three of the liberals in a 5-3 decision striking down Arizona’s infamous “show me your papers” immigration statute. (Elena Kagan, usually a reliable fourth vote for the left, recused herself.)

There is never any question about how Justice Clarence Thomas or Justice Samuel Alito will vote. Their records and their opinions demonstrate a fierce conservative ideology. Roberts is not so easily categorized, not so willing to be taken for granted.

He is also a student of history, and the Rehnquist court, which immediately preceded him, provides several important lessons. William Rehnquist, appointed by Richard Nixon in 1971, was a staunch conservative and intellectual heavyweight. By the time he assumed the position of chief in 1986, however, he occasionally proved to be less predictable.

In 2000, Rehnquist was presented with an opportunity to overrule the court’s 1966 decision Miranda v. Arizona, which established the famous “right-to-remain-silent” warnings that are written into the script of every crime procedural. Rehnquist had always held the Miranda decision in low regard. Now, it seemed, he might finally be in a position to persuade a majority of his colleagues.

Instead, Rehnquist authored a 7–2 opinion in Dickerson v. United States affirming Miranda as a “constitutional rule” that “has become embedded in police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture.” Rehnquist made it clear that while he might well have dissented from the original opinion, “the principles of stare decisis weigh heavily against overruling it now.”

That same year, however, the Rehnquist court lurched in the opposite direction, taking the unprecedented step of wading into presidential politics in Bush v. Gore. By a 5–4 margin, the conservatives, joined by Kennedy, stopped the recount of votes in Florida and handed the election to George W. Bush. In a bizarre, almost reasonless unsigned decision, the majority even made clear the case had no value as precedent.

Afterward, the court’s reputation cratered and Rehnquist, having presided over what is widely believed to be one of the most nakedly partisan decisions in history, saw his own legacy tarnished. Following her retirement, Sandra Day O’Connor, one of the justices who voted with the majority, admitted that it was probably a mistake to take the case, which, she said, “gave the court a less than perfect reputation.” Years later, when Roberts joined the majority upholding Obamacare, the conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer wrote in an op-ed for the Washington Post that Roberts felt compelled to do so in part because of the “bitterness and rancor” Bush v. Gore engendered, along with the belief that it “was a political act disguised as jurisprudence.”

What meaning will Roberts’ judicial philosophy, and the Rehnquist legacy, have if and when Roberts has an opportunity to lead his court in the overruling of Roe and Obergefell, among other lightning-rod precedents? My fervent hope and tentative predication—perhaps naïve and quite wrong—is that he will stop short of doing so.

Roe is not a single case; it is an impressive fortress of precedent spanning more than four decades. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, decided in 1992, a sharply divided Supreme Court made it clear that repeated attempts to overrule Roe—six at that point—would never work.

Writing a plurality, Justice O’Connor—the first and at that time only woman on the court—explained, “Where the Court acts to resolve the sort of unique, intensely divisive controversy reflected in Roe, its decision has a dimension not reflected in other cases and is entitled to a rare precedential force.” To overrule a decision that proved crucial to “[t]he ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation” would be “a surrender to political pressure and an unjustified repudiation of the principle on which the Court staked its authority in the first instance.” The result, they predicted, would be “the country’s loss of confidence in the Judiciary.”

The central holding of Roe was affirmed as recently as June 27, when the current eight-member court struck down a Texas law requiring that doctors performing abortions have admitting privileges at local hospitals and that the state’s abortion facilities conform to the standards of “ambulatory surgical centers.” These requirements, the majority held, were not designed to protect a woman’s health but rather to place an “undue burden” on her long-settled right to end her pregnancy. (Roberts joined a dissenting opinion written by Alito, which argued that the case should not have been heard in the first place. He has never explicitly called for the overruling of Roe). Seen in this context, Roe looks less controversial than indisputably settled.

Obergefell, decided in 2015, is a newer decision but also one borne of a steady accumulation of precedent. Two decades ago in Romer v. Evans, Kennedy, O’Connor, and the four liberals struck down an amendment to the Colorado Constitution that barred the state from protecting its citizens against discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 2003, the court, by a 6–3 vote, invalidated a state statute criminalizing sodomy in Lawrence v. Texas. To reach that result, Kennedy’s majority had to expressly overrule Bowers v. Hardwick, a 1986 relic upholding a similar Georgia law with this priggish sentiment: “respondent would have us announce, as the Court of Appeals did, a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy. This we are quite unwilling to do.” Voicing a barely concealed contempt, Justice Kennedy wrote, in Lawrence: “The central holding of Bowers has been brought in question by this case, and it should be addressed. Its continuance as precedent demeans the lives of homosexual persons.”

But if one relic can be overturned, why not others? It is a fair question. The short answer is that the court’s policy is not to deviate from stare decisis except under the most extraordinary circumstances. It is only permissible when the rule has proved unworkable or anachronistic, when so few people rely upon it that its disappearance will not cause a societal disruption, or when the facts have changed so dramatically “as to have robbed the old rule of significant application or justification.” Viewed through this prism, it is readily apparent why overturning the Bowers decision, a holdover from an era where it was perfectly acceptable to denigrate gay people, would be seen as a welcome step forward, in the same way that Brown v. Board of Education was embraced as doing away with the bigoted “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson.

The gay rights movement received another crucial assist when, in 2013, the court invalidated the Defense of Marriage Act of 1996, enacted under the Clinton administration, which limited marriage “to a legal union between one man and one woman.” Seen in this context, Obergefell looks less groundbreaking than inevitable. Though once again, Roberts dissented, this time writing for himself, Scalia, and Thomas. He wrote that while the idea of same-sex marriage “has undeniable appeal” there is no right to it under the Constitution.

* * *

What would a Roe reversal look like? No matter how the majority dresses it up, the bottom line would be the same. When we told you four decades ago that you had a constitutional right to control your own body, we were wrong. Whether or not you can terminate an unwanted, even dangerous pregnancy actually turns on the question of what state you live in and whether you are willing and able to go elsewhere.

What would an Obergefell reversal look like? No matter how the majority dresses it up, the bottom line would be the same. When we said the Constitution guarantees you the right to marry your same-sex partner and you did, we were wrong. Your marriage is not real, the financial benefits and social legitimacy you thought you had, those things are not real. Whether you are legally married or not depends on the state you live in and whether you are willing and able to go elsewhere.

The laws upholding the right to choose and the right to marry are not unworkable in practice and they are anything but anachronistic. Nor has there been a dramatic change in the underlying facts that robs the laws of their relevance or justification. The only reason to overturn these precedents is ideology: that is, a majority of justices who believe that abortion and gay marriage are morally wrong. Should Roberts allow the ideologues to have their way, the consequence will be a terrible disruption to the lives of millions of people who have come to rely on these constitutionally enshrined rights when making crucial life decisions. And the Roberts court would go down in history as having bankrupted the only branch left to stand by things decided.