The day after the presidential election, I stood in front of a class of foreign graduate students who had come to the United States to study U.S. and international law, trying to reassure them that they were not in danger of being deported.

“You are all here legally on student visas,” I reminded them. “President-elect Trump has never threatened to deport noncitizens who have permission to be in the United States.”

Then a student in a hijab raised her hand and asked, “What if I leave the country to visit my family for the holidays, or to do research? Will I be allowed back in?” Her question has no easy answer. Trump has vowed to “suspend immigration from certain terror-prone regions” within his first 100 days in office. The executive branch has enormous discretion to bar individuals or groups from entering the United States, even when the person seeking entry has a valid visa. I hesitated. “Perhaps you should travel before Jan. 20,” I told her finally. So much for calming their fears.

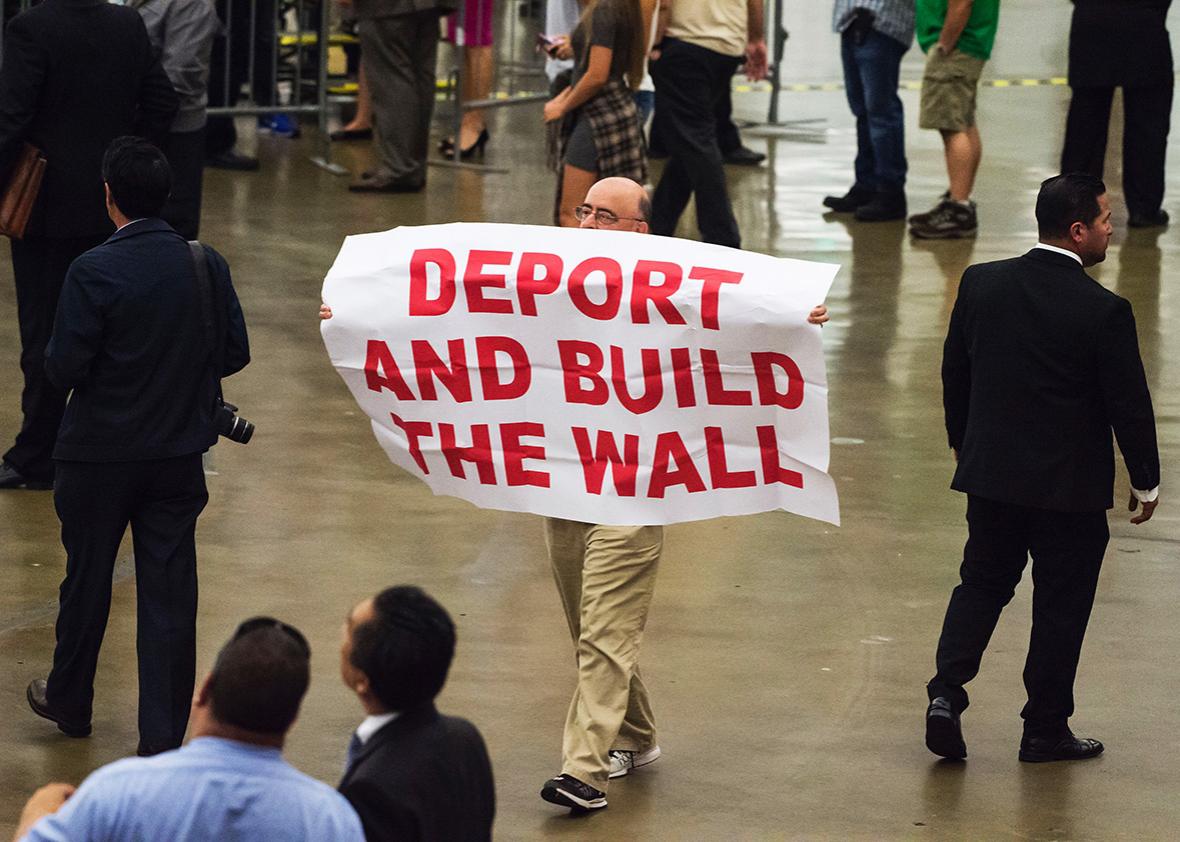

Trump’s presidential campaign centered on his plans to remake U.S. immigration policy. In addition to suspending immigration from yet-to-be named regions, he has pledged to reverse President Obama’s executive action granting certain undocumented immigrants temporary reprieves from removal, to build a “big, beautiful wall” between the United States and Mexico, and to deport millions of undocumented immigrants within a few years. Can he make good on those promises? How scared should my students be?

The president has unusually broad authority over immigration policy, but his power is not unlimited. President Trump, like presidents before him, may find it harder than he expects to persuade Congress, even a Republican-led Congress, to enact laws and fund his projects, to convince courts that his actions are constitutional, and to persuade the men and women who implement immigration law to exercise their discretion as he would like.

Trump can quickly implement proposals that do not require the participation of another branch of government. His proposed ban on immigration from certain regions—which replaced his previous and constitutionally suspect plan to ban all Muslims—is one of these. By focusing on geography and not religion, Trump avoids a court challenge that might have slowed down implementation. The Immigration and Nationality Act gives the president the unilateral power to deny entry to “any class of aliens” whom he believes are “detrimental to the interests of the United States,” which is all the authority Trump needs.

Likewise, Trump can easily rescind Obama’s 2012 executive action granting a temporary reprieve from removal to unauthorized immigrants who were brought to the United States as children. As of today, more than 700,000 undocumented youth have received deferred action and temporary work authorization, allowing them to come out of the shadows for the first time in their lives. Trump can eliminate this program with the stroke of a pen.

Building a wall across the southern border will be harder, however, because it requires money from Congress. A lot of money. A wall the scale of the one Trump promised—30 to 50 feet tall, stretching 2,000 miles—is estimated to cost between $15 billion and $25 billion. Trump has said that he will make Mexico pay, but he has not explained how he would force it to do so, and Congress does not appear willing to fund the cost in the meantime. In a recent interview, Trump implicitly acknowledged the need to scale back, agreeing that there “could be some fencing” instead.

Can Trump deport all of the approximately 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants currently living in the United States within a few years of taking office, as he had promised to do earlier in the campaign? Not on his own. Removals on a mass scale would require creating a deportation force with the authority to conduct daily raids on workplaces and homes, estimated to cost far more than that wall—$400 billion or more.

Even Trump has backed away from his more extreme positions on mass deportation. In a recent interview, the president-elect declared many undocumented immigrants to be “terrific people”—a jarring sentiment from a man who earlier said they all must go. He then explained that he would prioritize the removal of the “2 or 3 million” unauthorized immigrants who, he claims, have committed crimes. (That number is contested; the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute puts it at closer to 800,000.) But even that scaled-back deportation plan would be expensive. President Obama deported more people than any other president, expending all available funds to do so, and yet removed only about 400,000 people a year. Trump cannot deport millions in short order unless he can get Congress to go along with his plan.

In part, this is because deportation is not as simple as Trump’s rhetoric suggests. Noncitizens living in the United States have statutory and constitutional rights that must be protected in the removal process. They have the right to a hearing before an immigration judge, representation by counsel (if they can afford one), and they can appeal an adverse decision to a higher level of the agency bureaucracy—a process that can take years in the backlogged immigration courts. Furthermore, federal law provides some particularly sympathetic undocumented immigrants, such as trafficking victims and those eligible for asylum, the right to remain in the United States. Unless Trump can get Congress to repeal these laws, immigration officials can continue to use their discretion to give relief to at least some of the undocumented immigrants that Trump seeks to remove.

But there is one goal that Trump has already accomplished without the help of any other branch of government: He has made immigrants afraid. Just a few years ago, undocumented youth provided their names, addresses, and even fingerprints to the government in return for permission to live and work temporarily in the United States. Now these same immigrants fear that the data they handed over will be used to target them for removal. Undocumented immigrants who have lived in the United States for years, with U.S. citizen children and without a criminal record, were once a low priority for removal. They woke up on Nov. 9 knowing this was no longer the case. Even legal immigrants, like the foreign students I teach, worry that they will be expelled from the United States or denied reentry if they ever leave.

Perhaps this was Trump’s intent all along. Even if he cannot quickly build a wall or remove millions of unauthorized immigrants, he can instill fear, driving some immigrants to leave and others not to come in the first place. Fear alone can reduce immigration—both legal and illegal—without the federal government spending a cent. For this, at least, Trump gets all the credit.