In an election year that has brought out the very worst in us, the mounting anxiety around the act of voting itself should hardly surprise us. Taking cues from the Republican National Committee’s decades-old playbook, Donald Trump’s campaign and his supporters are subtly pushing an agenda of voter suppression, intimidation, and harassment. If America’s new “silent majority” of Hillary Clinton voters is afraid of its own polling places, that only benefits Trump and the Republican Party. The fact that voter intimidation imperils democracy itself? A feature, not a bug.

According to a Bloomberg Businessweek report last week by Joshua Green and Sasha Issenberg, the Trump digital campaign is running “three major voter suppression operations” aimed at lowering turnout among liberal millennials, young women, and black voters. An unnamed senior official says the campaign is targeting women online with information about Bill Clinton’s treatment of women and trying to target ads at black voters, especially in Florida, flagging Hillary Clinton’s “superpredator” remarks from the 1990s. Experts claim these tactics are not precisely vote suppression so much as efforts to discourage voting. The Trump campaign for its part denies any of this is happening.

The far bigger worry for many civil rights attorneys is the new vote-suppression message fomented in recent weeks by Trump himself, with his oft-repeated claims that the election system is “rigged” and that his supporters should go out and “watch the polls.” His admonishment that his supporters must themselves monitor minority precincts seems a recipe for voter anxiety at best and actual conflict at worst. Trump’s increasingly vocal warning that people are “going to walk in and they’re going to vote 10 times maybe” implicitly deputizes his followers to do something about all that supposed fraud.

How will this “monitoring” work in practice? Trump adviser Roger Stone told the Guardian that 1,300 volunteers for “Citizens for Trump” plan to conduct “exit polls” in nine cities in swing states with large populations of minority voters. Stone’s “Stop the Steal” project, which recruits volunteers from, among other places, Alex Jones’ conspiracy-minded radio audience, boasts of “targeted exit-polling in targeted states and targeted localities.” The Guardian goes on to quote polling expert David Paleologos, the director of the Suffolk University Political Research Center, who explains that effective exit-polling is done in bellwether precincts, not in majority-minority ones. “It doesn’t sound like that’s a traditional exit poll,” Paleologos explained. “It sounds like that’s just gathering data, in heavily Democratic areas for some purpose.”

Another Roger Stone group, this one called Vote Protectors, had a handy tool on its website that allowed volunteers to create an official-looking badge they could wear while ambling around polling places questioning people. After the Huffington Post reported on it, the site was taken down. As we have previously explained, it’s certainly legitimate to sign up to volunteer as a poll watcher. Roaming free with a sidearm looking for “people who can’t speak American,” as one Trump zealot put it, is not that. The rules for what constitutes legal poll-watching activities differ by state. Pennsylvania, for instance, requires that poll watchers be registered to vote in the county where they will serve. (Republicans have sued to be allowed to send poll watchers from rural counties into the cities.) In Ohio, where you must be formally credentialed as a poll watcher, uncredentialed Trump supporters have shown up to elections boards saying they are election observers. In any of these situations, poll watchers who berate or photograph voters could reasonably be considered to be in violation of federal statutes that prohibit conspiracies to intimidate voters.

All of this is happening as the number of federal election observers has declined significantly in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder. In 2012, federal observers were dispatched to jurisdictions in 13 states. This year, they will only be permitted inside polling places in some parts of four states. The remaining monitors also have diminished authority this time around. For one thing, they can no longer enter most polling places unless they are invited inside.

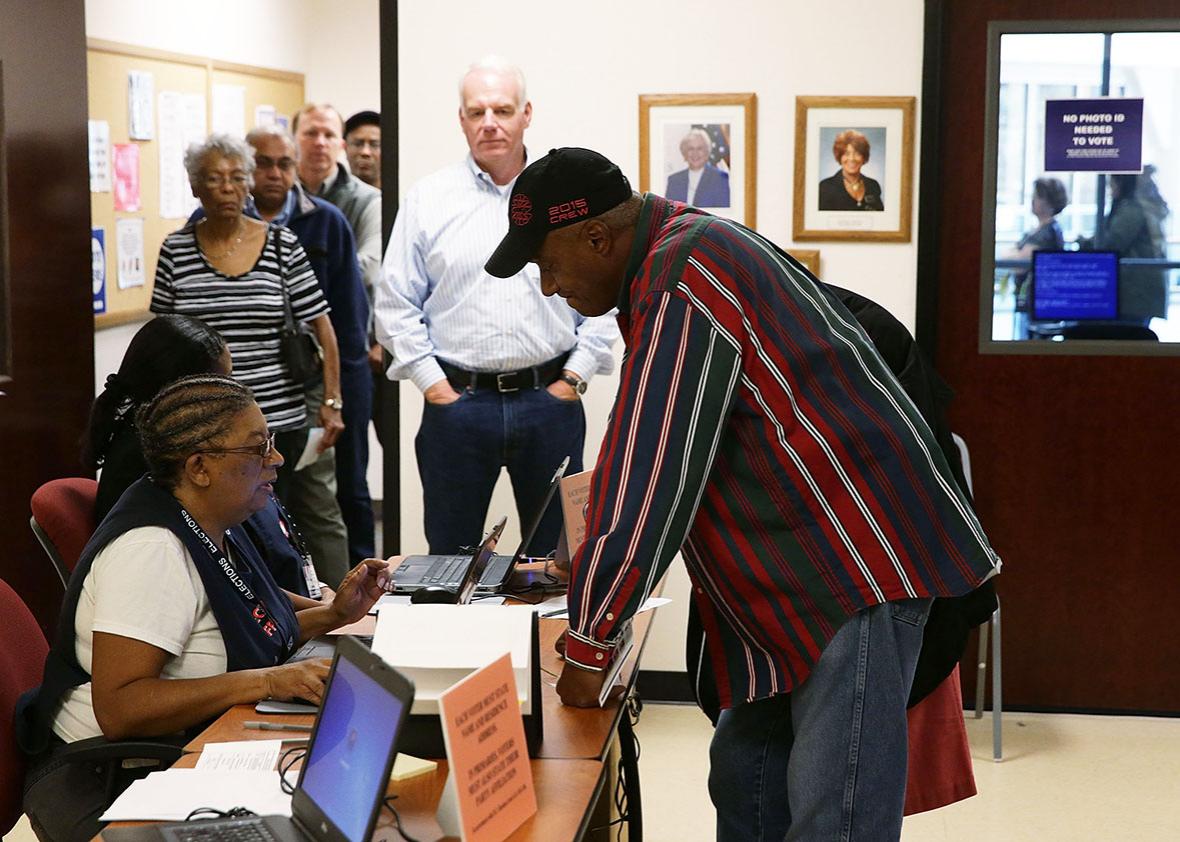

And all this also happens, as Mark Joseph Stern recounts, amid mass confusion in the Republican-led states that passed laws post–Shelby County that had both the purpose and effect of making it more difficult to vote. At least 14 states have new voting restrictions this year, ranging from confusing voter ID laws, diminished Sunday and early voting opportunities, and new registration requirements. Voters are figuring this out as they go. Even though many of these new laws have been struck down by the courts, we are now seeing concerted efforts in states like Texas and North Carolina to keep them alive in practice, through mass purges of the voter rolls and misinformation campaigns. Election workers in these and other states appear genuinely confused about what’s legal and what isn’t.

Democrats have responded with calls for more poll monitors and the dissemination of better information. They have also filed an array of lawsuits, attempting to halt voter-intimidation efforts in a number of states. One of the most fertile sources of litigation stems from the fact that the Republican National Committee has been operating under a consent decree since 1982. At the time, a federal court found the RNC had been attempting to intimidate minority voters by hiring armed off-duty police officers who would linger at polling places. In the 1981 New Jersey gubernatorial election, GOP officials also attempted to purge the voter rolls of black or Hispanic voters. The decree has been extended twice, applies across the country, and can be extended again next year, which is what plaintiffs now seek.

Last week, the Democratic National Committee filed suit in a federal court in New Jersey to try to block the RNC from coordinating with Trump’s campaign on any “ballot security” efforts. The lawsuit contends that participation in any such vote-suppression activity would be a violation of the consent decree. The Trump campaign is not itself bound by that decades-old decree, but if it works together with the party, it could presumably be in trouble with the courts. And in the New Jersey complaint, it’s alleged there is “ample evidence that Trump has enjoyed the direct and tacit support of the RNC in its ‘ballot security’ endeavors.”

As professor Richard L. Hasen of the University of California–Irvine School of Law noted on Sunday, another group of lawsuits was filed this week in Nevada, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, against the Trump campaign, the state Republican parties, and “Stop the Steal.” Led by Marc Elias, general counsel for the Clinton campaign, the suits are asking courts to step in and bar the defendants from monitoring polls, verbally harassing voters, and following them around with cameras. These suits allege the defendants have violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act and an 1871 law aimed at the Ku Klux Klan, both of which prohibit voter intimidation.

The Ohio suit, for instance, claims Trump “has made an escalating series of statements, often racially tinged, suggesting that his supporters should go to particular precincts on Election Day and intimidate voters.” The Pennsylvania complaint alleges more than 150 people have signed up as “poll watchers” in the state to ensure “cheating” doesn’t occur. The lawsuit alleges that though Trump’s campaign is not officially responsible for “poll watching” organizations, the campaign has spurred such vigilantes to take action.

Stone was quick to respond to these lawsuits, calling them frivolous. As he explained to Mother Jones, he plans to initiate a “neutral, scientifically based exit poll in order to compare the actual machine results with the exit poll results in 7,000 key precincts. Precincts are chosen [based] on one-party rule and past reports of irregularities—not racial make-up as falsely reported in the alt-left media.” Stone further explained to Newsweek that the 1,400 people across the United States who have volunteered for the project have been instructed to use neutral language and only approach people after they have voted. “Since we are only talking to voters after they have voted, how can we be intimidating them?” he said.

Just this week, the judge in the New Jersey RNC lawsuit ordered discovery on Trump and the RNC’s poll-watching efforts, with a hearing scheduled for this Friday. The court has ordered the RNC to turn over all communications between itself and the Trump campaign connected to poll watching, voter fraud, or “ballot security.” Hasen told me in an email this suit and all the others may have some value in the upcoming days, even if the intimidation itself cannot be halted. As he put it: “With just a week before the election, it is not clear that the courts will be directly ordering Republicans, the Trump campaign, or Stone not to engage in ‘voter intimidation.’ But the suits will help everyone know what the plans are, and hopefully getting everyone on record that there are no plans to intimidate voters will help keep things a little cooler on election day.”

In other words, if all the potential surprises are on the record, maybe there will be fewer surprises at the polls. Whatever happens next week, the systematic hassling and monitoring of voters in minority precincts will lead to longer lines and more frustration, which will itself decrease minority voting. As it turns out, it’s almost impossible to “rig” presidential elections. Rigging democracy itself, by compromising the right to vote, appears to be far simpler.