In his nearly 50 years on the bench, Circuit Court Judge Damon Keith has issued his share of blockbuster decisions—desegregating a racist public school system in Pontiac, Michigan, allowing affirmative action in police departments, and even halting President Richard Nixon’s illegal wiretap program. (In response, Nixon sued Keith personally; the Supreme Court unanimously vindicated Keith.)

But at 94 years old and still serving on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit, the federal judge still isn’t finished putting his stamp on American jurisprudence. This year, Keith heard a challenge to Ohio’s draconian new voting restrictions cracking down on early in-person and absentee voting. His colleagues voted to uphold the measures, which disproportionately burden minority voters.

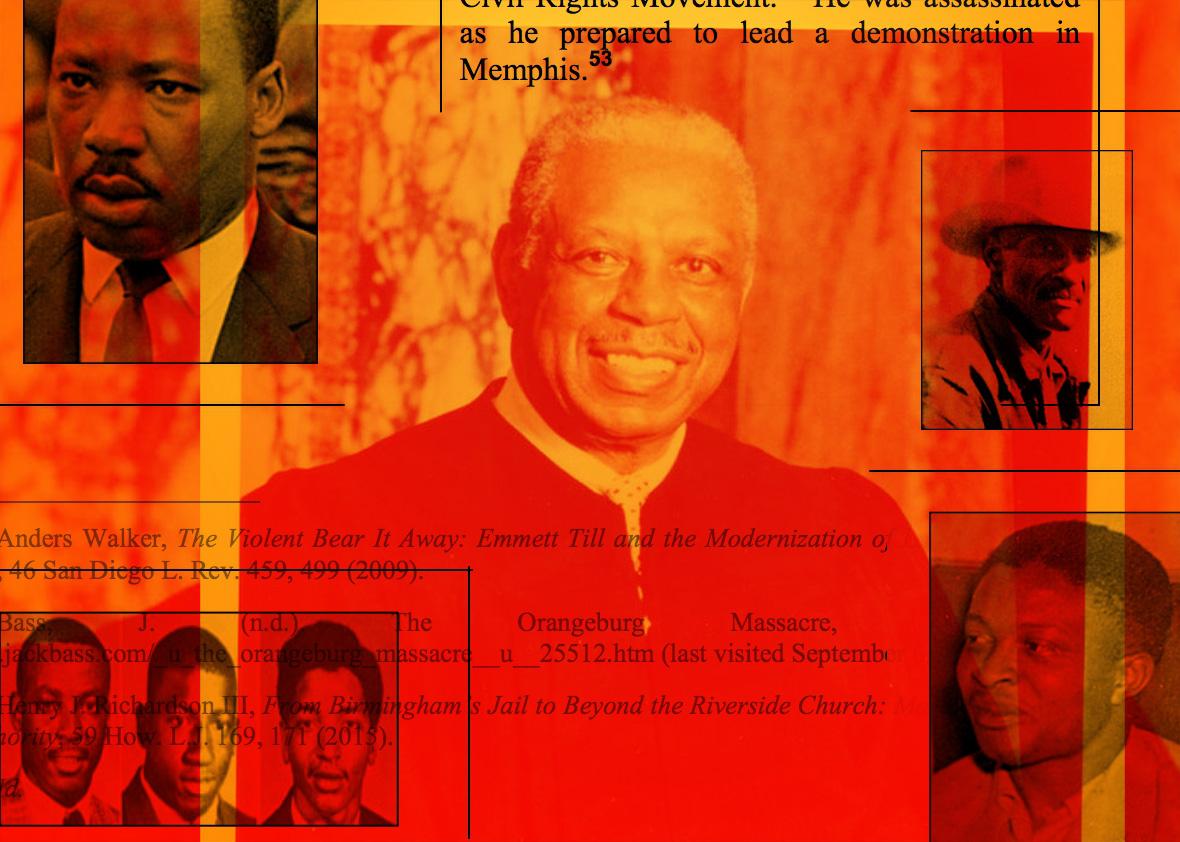

In response, Keith, who is the grandson of former slaves, wrote an extraordinarily impassioned dissent reminding the majority about “the utter brutality of white supremacy in its efforts to disenfranchise persons of color.” This bigotry, Keith explained, remains alive today and is very much evident in the attacks by Republican legislatures across the country on voting rights. “With every gain in equality,” he wrote, “there is often an equally robust and reactive retrenchment.” The modern effort to curb voting rights is part of that retrenchment, Keith noted—and the judiciary must not accept states’ pretext for disenfranchising minorities. Most remarkably, Keith included in his dissent a gallery “martyrs of the struggle for equality,” slain civil rights heroes “whose murdered lives opened the doors of our democracy and secured our right to vote.”

I recently spoke with Keith about his career, his devotion to civil rights, and this unusually fervent dissent. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Your most recent dissent criticized a ruling that did not, in your view, provide equal justice. Why did you include a gallery of slain civil rights heroes?

I wanted to dramatize the racist attitude of the majority. Look at those pictures. These are men and women who died for the right to vote. I was really so hurt by the decision of the majority of the court. My grandparents lived in Georgia, and they were not allowed to vote because of racism. I thought about them.

And you know, I was so disheartened by the attitude of Judge Boggs and Judge Rogers [the judges in the majority]. Thurgood used to say to us at Howard Law School, “dissents are very important.” And indeed, he’d quote cases where dissents were used. And this may sound trite to you, but in a dissent, you don’t have to get that second vote!

So I said in my dissent precisely what I thought the Ohio law was about, and I wrote about the struggle that we still have in this country for the right to vote. And I said, look at these pictures. All those men and women, white and black, Jew and gentile, gay and not-so-gay—this is what they lived for! This is what they fought for! This is what they died for!

I thought we should put that in writing.

Your dissent begins with your phrase from a previous opinion: “democracies die behind closed doors.” You penned it in one of your most famous decisions, which held that the First Amendment required public access to post-9/11 deportation hearings. What exactly does the phrase mean to you?

It means we’ve got to have an open society. We can’t have judicial hearings for just a few. I remember, going back a long way to when I was practicing law in Detroit, most of my practice was in a criminal court. I would be in there with a client of mine and the prosecutor would go into the judge’s chambers by himself and then stay there for an hour. My client would say, “What are they doing in there?” I’d say, “I don’t know.” Then the prosecutor and judge would walk out together!

My experiences have indicated to me that we have to have an open society so all people can be heard and be a part of major decisions—especially constitutional ones.

You were good friends with Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, your mentor at Howard Law. How did your relationship with Marshall affect your judicial philosophy?

Thurgood was a strong man and I admired him tremendously. He used to tell us to remember those four words engraved on the Supreme Court: Equal justice under law. He’d say, “The white man wrote those letters on the Supreme Court. Now use those words to make to make equal justice under law a reality.”

Thurgood also used to tell us: “Use the law as a means of social change.” I tried to do that throughout my judicial career. And God bless me, I was born on July 4, 1922. July Fourth! And that wasn’t by accident. I think God just put me there. Now look at my cases. I think, I hope they reflect those four words: equal justice under law.

You’re 94 years old. Why do you still sit for cases at an age when most judges have long retired?

Well, I don’t like to talk about myself! But I would say that it’s still important to me to make a contribution legally, especially through a dissent in cases involving voting rights—which my grandparents could not use and other blacks and minorities could not use for years. It’s nice to make a contribution.

You’ve actually made quite a lot of contributions.

[Laughs.] I’m just a Detroit boy who got his voice.