During his “I’m With Her (More or Less)” speech at the Democratic National Convention on Monday, Sen. Bernie Sanders made a vitally important argument about the 2016 campaign: That it’s about more than who the president for the next four years will be; it’s about who will be on the Supreme Court for years to come. “This election is about overturning Citizens United, one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in the history of our country,” he said. He added that Hillary Clinton’s future justices “will also defend a woman’s right to choose, workers’ rights, the rights of the LGBT community, the needs of minorities and immigrants, and the government’s ability to protect the environment.”

Every last one of those promises is very serious business. But Sanders neglected to mention one of the other worst Supreme Court decisions in the history of the country—one with tangible implications for the November elections and one that has gotten far less attention than his much-loathed Citizens United. It has had as much to do with disenfranchising America’s have-nots as the campaign finance case. It’s the case that made voting an uphill battle again.

In 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, the court issued a landmark decision that eviscerated core components of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. We’re living with the fallout today, and the next president and his or her judicial appointments will go a long way toward determining when and how basic voting rights are respected in this country. Last week demonstrated the centrality of the courts to broader voting rights more than any other in 2016, with a bevy of critical court rulings that showed that the fight is a long way from done.

The Voting Rights Act was originally enacted in 1965 to eradicate the racially tainted voter suppression that plagued the Jim Crow South. When the court voted 5–4 to strike down Section 4 of the act, it was an enormous change to the law, freeing many jurisdictions with historical records of discrimination from having to get federal preclearance before changing their voting laws. After Shelby County, several states took advantage of their new freedom to create voting laws with discriminatory effects without the feds looking over their shoulders. Some waited only a few days to restrict voting again. And in the future—possibly the very near future—the court will look again at state efforts to limit voting.

The 2016 election will be the first post–Shelby County presidential race, and it could come down to contested votes in some of the very same states that have fiddled with their laws in recent years. You aren’t merely electing your president come November. You’re picking the justice who will help determine whose votes can be discounted and whose are inviolate.

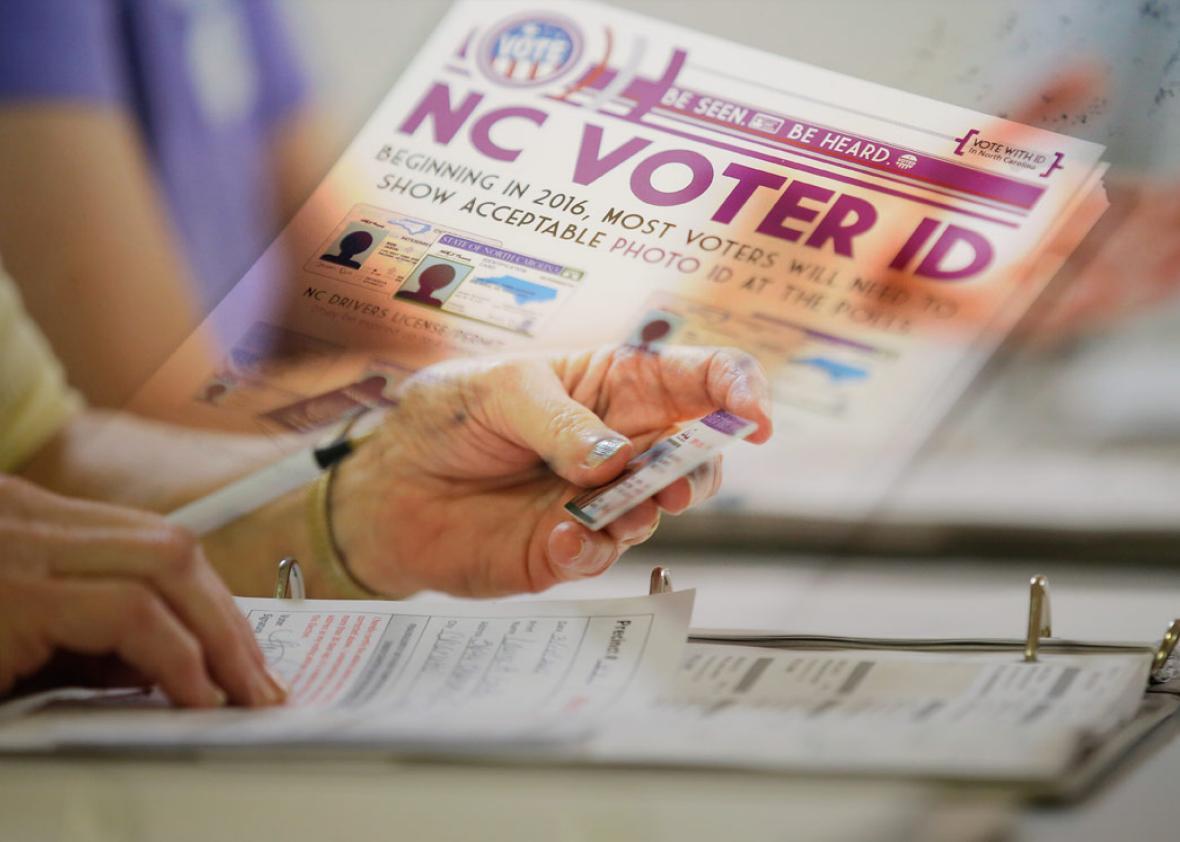

Last week saw three major victories for voting rights. Federal courts struck down draconian voter ID laws in Texas and Wisconsin, and a federal judge in Michigan struck down a rule that would have barred straight-ticket voting, a state system that allows voters to cast ballots for every candidate from a given party with a single vote. The effort to do away with that long-standing system would have disadvantaged chiefly black voters, because there is a strong correlation in Michigan’s biggest counties between the size of the black voting population and the use of straight-ticket voting. Also last week, in one of the biggest voting right challenges in recent history, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Texas’ Senate Bill 14—one of the toughest voter ID laws in the nation—disproportionately burdened black and Hispanic voters, in violation of part of the Voting Rights Act. And a federal judge in Wisconsin similarly ruled that the state’s voter ID requirement was excessively restrictive and that a voter who lacked the appropriate ID could thus still cast a valid ballot provided he or she signed an affidavit.

These rulings were all important wins for voting rights. The judges in them went out of their way to explain that voter fraud is extremely rare and that suppressing votes is one of the most pernicious forms of election stealing we have. Judge Lynn Adelman noted crisply that “there is virtually no voter-impersonation fraud in Wisconsin.” Judge Catharina Haynes of the 5th Circuit commented that almost 1 in 20 voters in Texas lacked the ID required to vote under the new law and that poor, Hispanic, and black voters were significantly less likely to be in possession of the correct documents. And the Michigan judge, Gershwin A. Drain, went so far as to note that our current election discourse seems to lend itself to “racial appeals from its candidates,” some of which “have been implicitly ethnocentric.”

These courts, in other words, are now closely watching the efforts at voter suppression and finding that the myth of voter fraud does not justify the tangible harms these laws do to many voters.

But last week also saw a major voting setback when the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that Gov. Terry McAuliffe’s move to restore voting rights to 200,000 disenfranchised felons violated the Virginia Constitution. By a 4–3 margin the state’s highest court ruled that McAuliffe had gone beyond his executive authority by ordering the restoration of voting rights in one fell swoop. The result of that ruling was to effectively disenfranchise 20 percent of the state’s black voters. (McAuliffe’s critics say the order was a transparent effort to throw the election to Clinton in November.)

Still, the ruling also held that McAuliffe is allowed to lawfully restore voting rights for former felons, but only by individually signing the restoration orders on a case-by-case basis. That’s just what he has now pledged to do in all 206,000 or so cases. McAuliffe was clear that in his view, this was the only appropriate response to the successful lawsuit initiated by state Republicans.

The adverse Virginia ruling came on the heels of word from Reuters that the Justice Department was deploying the lowest number of federal election observers since the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965. The Justice Department believes that as a result of the Shelby County ruling, it lacks authority to select voting areas at most risk of racial discrimination and deploy observers there. The upshot is that only five states—Alabama, Alaska, California, Louisiana, and New York—have been authorized by federal court rulings to have their votes overseen by federal monitors. Many more states that might benefit from such monitors won’t get them this fall.

“Federal observers [help] to block and deter discriminatory conduct that might otherwise go undetected,” noted Kristen Clarke, president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “[T]he Justice Department’s decision to terminate the federal observer program further underscores the need for Congress to take action now to restore the Voting Rights Act in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2013 Shelby County decision.”

The mass confusion sewn by the raft of new voter ID laws passed in recent years, countered by the myriad lawsuits challenging them, plus the willingness of parties on both sides to believe that the voting system is “rigged” means that an election free of the sort of confusion we’ve seen in recent presidential votes is more important than ever. And while voter ID laws seem to have suffered some body blows last week, the ghosts of Shelby County will continue to take many forms, reminding us that Sanders’ point about the court is even more critical than he described Monday night. Let’s not allow ourselves to forget that amid the speeches and the songs and the promises of this week’s convention, decadeslong efforts to make voting ever harder for minorities, the elderly, the poor, and former felons may be where this election is decided. The Constitution provides that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” In 2013 five members of the Roberts court felt pretty confident that the time for extraordinary measures to protect minorities from race discrimination in voting was simply past. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented, famously writing that the court’s decision was like “getting rid of an umbrella in the middle of a rainstorm just because you were not getting wet.” Let’s bear in mind that the results of this election will go a long way toward deciding the extent to which the courts will protect the voting rights of all Americans or leave the most vulnerable out in the storm.