The Supreme Court reversed the 30-year-old capital murder conviction of Timothy Foster on Monday, finding that prosecutors in Georgia engaged in blatant racial discrimination in striking every black person from the jury. The state trial and appellate courts upheld the prosecution’s contention that race played no role in its jury selection.

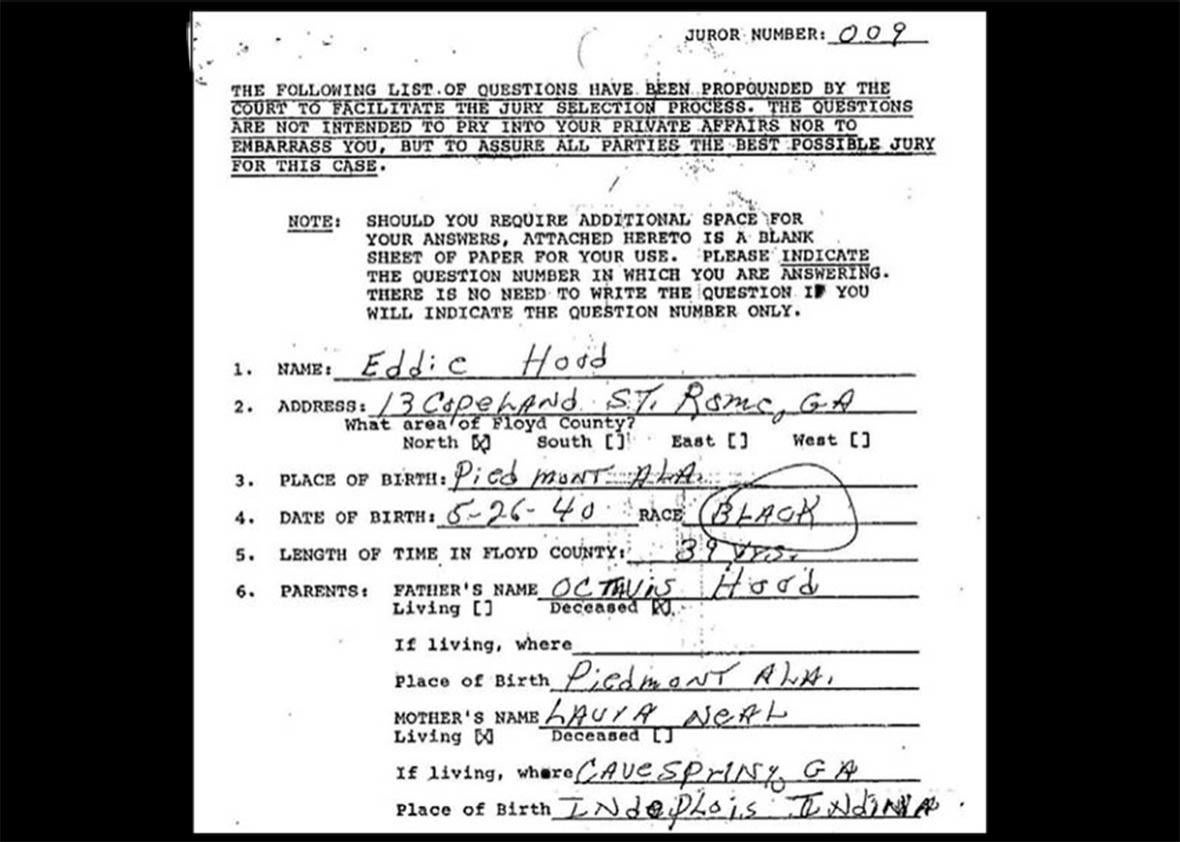

However, decades later, documents were discovered in the prosecutor’s files that destroyed the prosecution’s contention, including a list of jurors’ names with the names of black jurors highlighted, an affidavit from an investigator with the notation, “If it comes down to having to pick a black juror, [this one] might be okay,” and handwritten notes denoting prospective black jurors as “B# 1,” “B# 2,” and “B# 3.”

The court further ridiculed the prosecutors’ claim of race neutral strikes as “nonsense” by showing that they accepted white jurors for giving the same answers to questions on which they struck black jurors. The court also exposed the prosecutors’ self-serving testimony as fabricated.

It is inescapably clear, however, that despite the Foster decision, prosecutors can and do still remove black persons from jury service with impunity simply by concocting purportedly race-neutral reasons. Indeed, but for the serendipitous discovery of damning evidence in the prosecutor’s files in this case, prosecutors would have been able to evade their constitutional duty easily.

The Supreme Court, in the 1986 case of Batson v. Kentucky, had previously declared that striking jurors because of their race is unconstitutional but allowed prosecutors to strike jurors for any race-neutral reason. And prosecutors have been adept at concocting outlandish reasons for their strikes that almost always escape judicial scrutiny, such as “didn’t seem sincere,” “ seemed inattentive,” “gut feeling,” “the way they answered questions,” male wearing earring, living alone, living with a girlfriend, overeducated, undereducated, unemployed, employed as a barber, agreed with the O.J. Simpson verdict, watches gospel programs on TV, particular surname, “hunches,” and on and on.

Indeed, the Foster case demonstrates some of the patently phony “race-neutral” justifications and workarounds that lower courts generally allow prosecutors to get away with. Before the Supreme Court unmasked such justifications as a sham thanks to the random discovery of that file, a prosecutor in that case had claimed he struck one of the black jurors because she was too young. She was 34, but the prosecutors did not strike eight white prospective jurors under the age of 36, and two of those jurors were 21 years old. The prosecutor claimed he struck a black juror because she was divorced, but the prosecutor did not strike three white jurors who also were divorced. The prosecutor claimed he struck one of the black jurors because his son “basically had done the same thing this defendant was charged with,” but Chief Justice John Roberts ridiculed this claim as “nonsensical,” “fantastic,” and “implausible,” noting that the juror’s son had stolen hubcaps and received a suspended sentence; the defendant was charged with brutally murdering a 79-year-old widow after sexually assaulting her.

The Court also exposed false statements by the prosecutors. One of the prosecutors claimed that he had listed in his notes one of the black jurors as “questionable,” but the prosecutors’ jury list referred to this juror, along with all other black potential jurors, as a “definite NO.” The court also exposed as fraudulent the prosecution’s deliberate misrepresentation of one of the black jurors’ views on capital punishment.

These sorts of superficial and false justifications were not uncommon for years—and still exist today. Not surprisingly, prosecutors are actually trained on how to evade the Batson rule. In a 1987 training video leaked from the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, new prosecutors were trained when they encountered black jurors to “mark something down on a little sheet that you can articulate later” and “to ask more questions of those people [black jurors] so it gives you more ammunition to make an articulable reason as to why you are striking them not for race.” As recently as the 1990s, North Carolina prosecutors held training sessions with handouts for “Batson Justifications: Articulating Juror Negatives,” which listed a variety of reasons for striking black jurors based on the kinds of pre-textual reasons noted above.

It should therefore come as no surprise that in many states, as studies have shown, prosecutors strike black jurors far more often than white jurors. In Louisiana, prosecutors have removed black jurors three times more often than other jurors. In North Carolina and Alabama, prosecutors struck black jurors at double or triple the rate of others. This disparity is often most observable in capital cases. In North Carolina between 1990 and 2010, prosecutors struck potential black jurors in capital cases at twice the rate of other jurors.

Why do prosecutors seek to remove black persons from juries? The answer seems obvious. Prosecutors have long believed that striking black jurors improves their chances of convicting a black defendant. Prosecutors assume that black people are more likely than white people to have negative feelings about government, to have had bad experiences with the police, are more likely to have been targeted for arrests and forcible stops than white people, are more likely to have been imprisoned for minor drug crimes, and are more likely to believe that crimes against black victims are prosecuted less aggressively than crimes against whites.

The Batson rule as it is currently enforced is perceived by courts and commentators as a charade that diminishes the integrity of the criminal justice system. Can anything be done? One proposal is to prohibit prosecutors—indeed, all trial lawyers—from being able to remove potential jurors arbitrarily without having to give any credible reason. Another proposal is to carefully track the way prosecutors select juries with special scrutiny on the racial makeup of the jury in the same way that police are tracked when they make forcible stops and frisks.

Sadly, the evidence against the prosecutors in the Foster case was a fluke: The prosecution files contained the proverbial “smoking gun.” But in thousands of other criminal trials throughout the country, prosecutors are able to hide deliberate racial discrimination under the cover of legitimate race-neutral reasons—and prosecutors almost always get away with it.

The lone dissenter in Foster, Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote what can generously be described as a perverse, embarrassing, and just plain stupid opinion. That dissent is an embarrassment and a disgrace, but the majority opinion itself does little to combat the actual problem of prosecutors regularly violating the Constitution to get rid of unwanted black jurors. Until that problem is fixed by the court or the legislature, miscarriages of justice like what occurred in Foster will continue to take place.