This week, the Little Sisters of the Poor told the Supreme Court that they are finally willing to let the government accommodate their religious beliefs. In a case argued last month, Zubik v. Burwell, the order of nuns challenged the government’s efforts to work around their religious objections to paying for health insurance that covers contraception. The government had offered an accommodation, relieving them of any responsibility to provide contraception—it only asked that they notify either the federal health agency or their insurer of their religious objection. But the Little Sisters complained that by giving any kind of written notice, they would be triggering contraceptive coverage for their employees, who staff their nursing homes for impoverished seniors. They also objected that the government would make them complicit by “hijacking” their health plans to provide such coverage, even if there was no actual cost to the religious employer.

Now the Little Sisters are telling the Supreme Court that as long as they don’t have to communicate their objection in this way, their consciences are clear. And they are joined in this turnabout by the numerous other religious nonprofits participating in the litigation.

Why the change? Last month, after hearing the Little Sisters’ appeal, the Supreme Court took the highly unusual step of ordering the parties to address whether there is a means by which religious nonprofits can give notice of their objection to providing contraceptive coverage in a way that allows their employees to receive that coverage. The idea, floated by the Supreme Court, is that religious nonprofits would not be involved in paying for contraceptive coverage beyond informing their insurer that their insurance plan would not include contraception because of a religious objection. At that point, the insurance company would inform the employees, and the same insurance company would provide coverage.

Somewhat surprisingly, in a brief filed on Tuesday, the Little Sisters said, “Yes,” to the Supreme Court’s proposal, eagerly embracing the modified accommodation. They indicated a willingness to purchase plans that do not include contraceptive coverage, and they raised no legal objection to the government requiring the insurance companies that provide those plans to cover contraception for their employees. The distinction seems highly formalistic. Under the court’s suggested compromise, the nonprofits still express their religious objection, but they do so by purchasing plans that don’t include contraceptive coverage. Everything else remains the same.

Is there a meaningful difference between the government’s existing accommodation and the accommodation proposed by the court? Does the sincere religious objection to the provision of contraception really turn on whether religious groups object by choosing a plan that does not include contraceptive coverage, as opposed to giving express notice? Since the only acceptable reason for excluding contraception coverage is religious, the message sent is exactly the same.

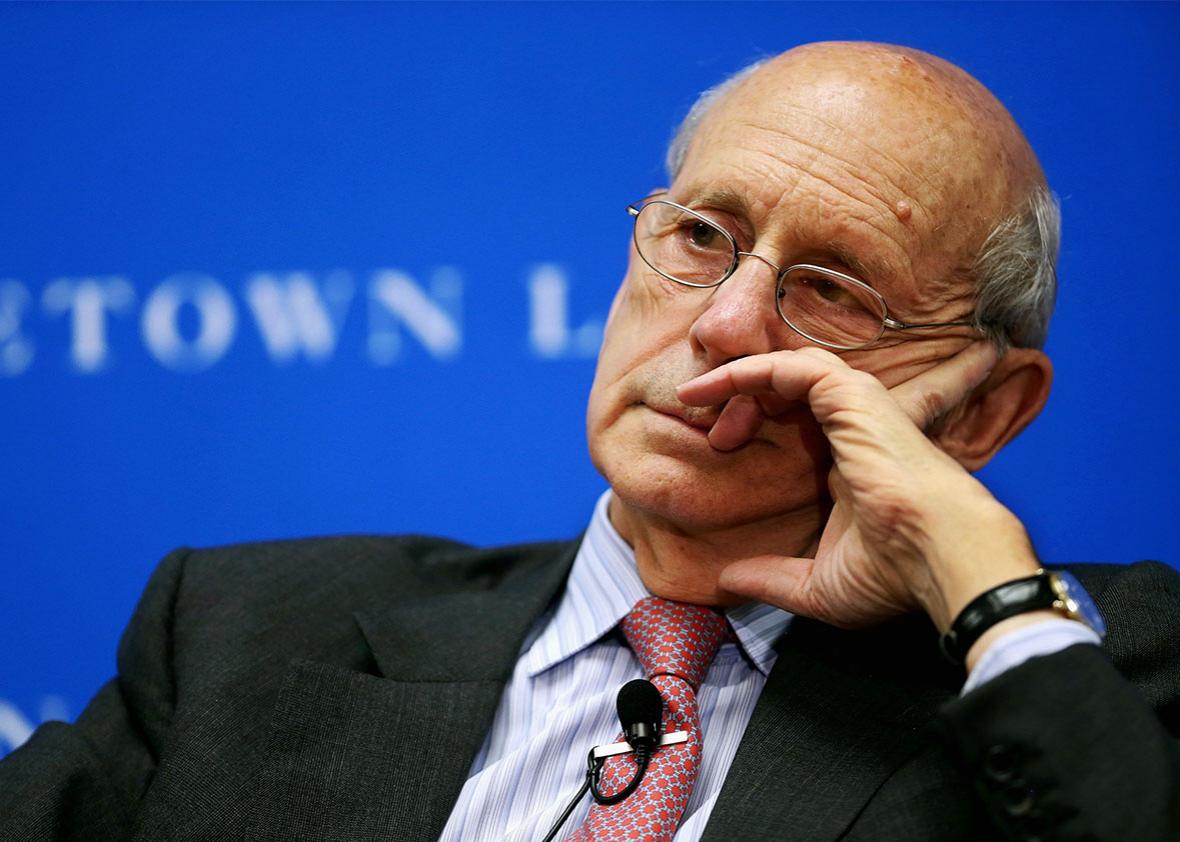

The court might have to accept the Little Sisters’ word that there is a difference, but there might also be strategic reasons for their embrace of the court’s proposed alternative. On a 4-4 court, Justice Stephen Breyer is now the swing vote for Little Sisters and other cases where the lower courts ruled for the government. A tie vote means that in those seven circuits the government wins, a big loss for the petitioners. (Only the Eighth Circuit ruled against the mandate, and that ruling would stand in the event of a tie—in all the other circuits, the government would win.) If the religious nonprofits are worried about Breyer’s vote—and perhaps also Justice Anthony Kennedy’s—then maybe they realize that the court is trying to throw them a lifeline, and they are taking it.

For its part, the government is wary of further extending the existing accommodation. In supplemental briefing also filed on Tuesday, the government emphasized the similarity between the court’s proposal and the regulation currently in place. The government also noted that the religious nonprofits had never before suggested any willingness to accept such a proposal, raising the prospect that other religious groups, not part of the current litigation, will come forward and object to this new settlement. In fact, the government has every reason for concern. After Hobby Lobby, which granted a religious exemption to for-profits that objected to covering contraception, the court gave nonprofits the option of notifying HHS of their objection. Now that some of those nonprofits are challenging that court-created option, the government wants to be sure that whatever option the court accepts this time is insulated from further litigation.

What is apparent to the government—and what some commentators seem not to have understood—is that the four liberal justices who dissented in Hobby Lobby are not going sign onto a decision in this case that results in employees permanently losing their statutory right to contraceptive coverage. If the majority in Hobby Lobby was unclear on this point—that accommodations are only permissible if they do not impose significant burdens on employees—the dissenters’ views were unmistakable. And those dissenters now control the outcome in all but one circuit.

The Little Sisters know this, and so they need to grab onto any compromise that will give them a “victory” even if it turns on a distinction without much difference.

But how can the court now write an opinion to reflect the compromise it seems to have proposed? The court could observe that there is an accommodation that was unknown to the government before the litigation—and that was revealed only after the court proposed it. It could further hold that accommodating religious nonprofits in this way is permissible because there are no harms to the statutory rights of third parties, namely, the employees who have a right to contraceptive coverage. Perhaps this results in a plurality opinion, with Justices Kennedy and Breyer in the middle, and the six other justices arrayed in concurrence/dissent.

It would be preferable to reject the Little Sisters’ new position on the grounds the government had already sufficiently accommodated them—as seven courts of appeals decided. But maybe the court is looking for a compromise. Justice Breyer is a pragmatist and a problem solver. When he upheld one Ten Commandments display and struck down another in companion Establishment Clause challenges, he was trying to manage the religious culture wars through compromise. Whether that kind of compromise is good for constitutional doctrine beyond resolving specific cases is an important question. In Zubik, a Breyer-inspired compromise would do the least damage to future free-exercise doctrine if the decision is presented as unique to the insurance-contraception setting, and if it makes clear that no accommodation claim will be entertained if it imposes more than de minimis costs on third parties.

We should also not lose sight of the fact that employees have been harmed in the process of this litigation. At the end of its supplemental briefing, the government explained that “because of injunctions and other interim relief entered by the lower courts, none of the [tens of thousands of] affected women are presently receiving the full and equal health coverage to which they are statutorily entitled.” It is unfortunate that the constitutional interests of those women are not directly represented in this litigation. As we have argued previously, employees who have been denied statutory benefits as a result of religious accommodations deserve protection under the Establishment Clause. They should not be deprived of their rights while the court attempts to settle this dispute.