In 1995, John Adair and John Mix, a gay couple living in Riverside County, California, were murdered in their home. Both men were shot in the face. Mix died immediately, but Adair lived long enough to call 911 and respond, when the police asked him who the killer was, with something that sounded like baca. Johnny Steven Baca, the couple’s live-in housekeeper, was arrested and charged a few days later with first-degree murder. His trial took place in Riverside County Superior Court, in the city of Indio, about 130 miles east of Los Angeles.

The prosecution’s theory was that Baca killed Adair and Mix in a murder-for-hire plot masterminded by Adair’s adopted son Tom. But the evidence of a conspiracy was thin. Baca did not confess, and no forensic evidence linked him to the murder weapon, which had been recovered at the crime scene near Mix’s body. Tom Adair was never charged with the murders and did not testify against Baca. After John Adair’s death, Tom inherited nearly half a million dollars from his father’s estate, but there was no evidence that Baca knew about the inheritance or that he received any of Tom’s money.

Instead, the trial prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Paul Vinegrad, relied on the testimony of Daniel Melendez, a jailhouse informant who was facing his own murder charges for killing a man named Mario Gomez with the help of an accomplice. Melendez told the jury that Baca had confessed to killing Mix and Adair at Tom’s behest. Asked directly by defense counsel if he was receiving any favors from Vinegrad’s office in exchange for his testimony, Melendez said no.

Vinegrad then called his colleague, Deputy District Attorney Robert Spira, who was in charge of prosecuting Melendez. Under oath, Spira told the jury that Melendez had agreed to plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter in exchange for Spira recommending a 14-year prison sentence. Spira was emphatic, however, that this deal was based solely on Melendez’s decision to inform on his co-defendant in the Gomez murder. Melendez’s testimony against Baca, Spira told the jury, had no bearing on the state’s leniency, which was substantial. Melendez’s initial murder charges carried the possibility of a life sentence.

Several months before Baca’s trial, Spira had made the same representation to Melendez’s sentencing judge, H. Dennis Myers. The judge was incredulous that Melendez would testify against Baca simply out of the goodness of his heart, thinking, in Myers’ words, “Well, heck, I will go up and testify in another murder case and just—I don’t expect anything from them.” Melendez’s attorney chimed in, telling Myers that his client had in fact been “led to believe there would be a reward at the end of the rainbow.”

Given Melendez’s cooperativeness in the Baca case, Myers said he was inclined to give him less than the 14-year sentence the state had already promised. Myers lacked the legal authority to do so, however, if the prosecution opposed him. He then asked Spira’s colleague, Kevin Ruddy, who was also present, “I’ll just cut to the quick. What is the people’s position if the court further went down from the 14? Further downward sentence?” Ruddy replied, “We would not appeal the court’s decision.” Melendez ultimately received a 10-year sentence for his cooperation in both cases.

Spira was in the courtroom representing the state of California when the court pronounced Melendez’s final sentence. Testifying at Baca’s trial, however, he concealed the fact that Judge Myers had explicitly taken Melendez’s testimony against Baca into account in his sentencing and at times affirmatively lied about it, insisting that the only reason Melendez got the extra sentence reduction was due to a change in the sentencing law that happened to benefit him. Baca was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to serve 70 years to life in prison.

After unearthing the transcript showing what actually transpired at Melendez’s sentencing hearing, Baca’s lawyers filed an appeal, demanding that his conviction be overturned due to prosecutorial misconduct and false testimony. The California Court of Appeal agreed that the state’s conduct was egregious. The justices characterized Spira’s testimony as “sheer fantasy” and took a dim view of the district attorney’s elaborate verbal tap dance to defend it by arguing that Melendez received no extra favors from the state in “exchange” for testifying against Baca because the windfall technically came from Judge Myers. “This kind of hypothetical parsing does not dispel the highly misleading nature of the testimony, which sent a single, unwavering, blatantly false message to the jury: that the informant sought nothing and got nothing for testifying against the defendant.”

And yet, the state appellate judges declined to reverse Baca’s conviction. Although Melendez and Spira had perjured themselves, the judges found that their false testimony did not prejudice the outcome of the trial. While the question was “close,” they concluded, “in the end, we do not see a probability of a different outcome.”

It is far from clear that Johnny Baca is actually innocent of the brutal double homicide that took the lives of Mix and Adair. Unlike defendants in recent years who have been exonerated by DNA evidence or new testimony, no information has surfaced to show that he did not commit the crime. And yet, his constitutional right to a fair trial was clearly violated. In theory, the Bill of Rights guarantees all defendants, even guilty ones, be protected from prosecutorial misconduct and false testimony. In practice, the structure of our criminal justice system gives prosecutors strong incentives to pursue convictions at all costs and to stand by ill-gotten verdicts. State appellate judges, who like prosecutors must stand for election, are often disinclined to overturn a trial court’s decision, even a compromised one.

Even the federal courts, which are free from the electoral pressures of the state system, have in recent years ignored the plights of defendants like Johnny Baca, their hands tied by legislation intended to keep federal judges from meddling in state affairs. Baca, however, enjoyed one bit of good fortune. In 2015, after more than a decade of filing and losing appeals, his case reached the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, one level below the Supreme Court, and home to a judge fighting a public war against prosecutorial misconduct.

* * *

The 9th Circuit, one of the nation’s 13 federal appellate courts, stands apart from the others. It is by far the largest, with more than two-dozen full-time judges presiding in nine states. It has also been the quickest circuit court to embrace technology. It has its own YouTube channel, where the curious viewer can watch live streaming oral arguments. No other federal court of appeal records its oral arguments on video.

The 9th Circuit is also regarded as the most liberal of the circuit courts, known for its repeated clashes with the Supreme Court, particularly in cases like Baca’s, where a prisoner is asking a federal court to intervene in a state court case. In 1996, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. It bars federal judges from overturning a state court decision unless it was “contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States,” or involved “an unreasonable determination of the facts.” The statute, enacted in the wake of the Oklahoma City bombing by a Republican-controlled Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, culminated a decadeslong effort by conservatives to sharply curtail the ability of convicted inmates to seek redress in federal court for constitutional violations they alleged occurred in the state courts where they were convicted.

The Supreme Court, which has tilted conservative on many criminal justice issues since Sandra Day O’Connor and then Anthony Kennedy became the swing votes, has interpreted AEDPA strictly. For a federal court to reverse a state court decision under AEDPA, it is not enough that the state court got it wrong. A prisoner can win only if the state court got it so thoroughly and completely wrong that its decision was irrational—essentially, indefensible. In 2011, the court ruled in Harrington v. Richter that even when the state court provided no reason whatsoever for denying a prisoner’s constitutional claim, the decision must be upheld unless it was “was so lacking in justification that there was an error well understood and comprehended in existing law beyond any possibility for fair-minded disagreement.”

Federal judges who have looked for a way around AEDPA have typically found themselves slapped down by the Supreme Court. This is particularly true in the 9th Circuit, home to the judiciary’s most incisive critics of AEDPA. Judge Stephen Reinhardt, a Carter appointee, has been prolific and outspoken in his condemnation of AEDPA for nearly two decades. The practical effect of the Richter decision, Reinhardt has written, was that, “state courts can ignore or summarily deny meritorious claims as long as a federal judge can conjure up any possible way that existing Supreme Court precedent would compel a contrary conclusion.” Of AEDPA generally, he has said, “it resembles a twisted labyrinth of deliberately crafted legal obstacles that make it as difficult for habeas petitioners to succeed in pursuing the Writ as it would be for a Supreme Court Justice to strike out Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, and Mickey Mantle in succession—even with the Chief Justice calling balls and strikes.”

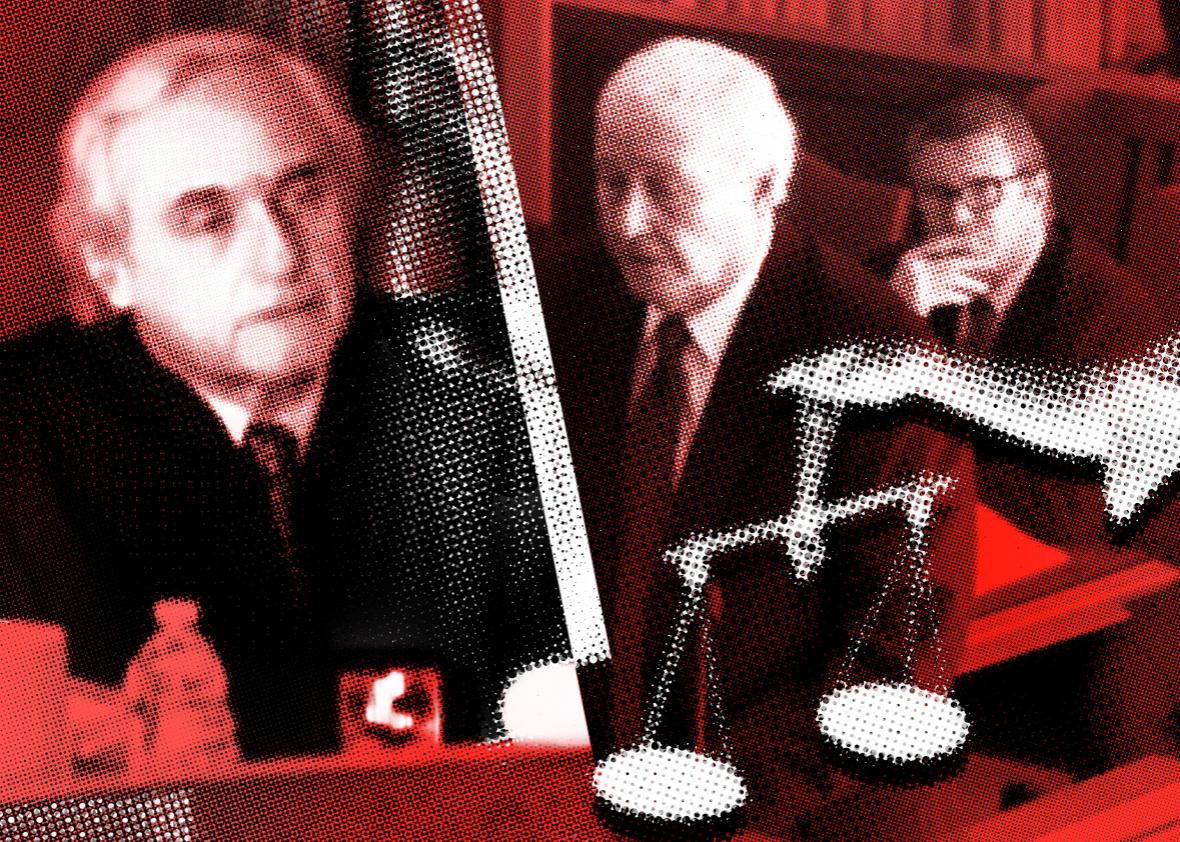

Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

But it is Reinhardt’s colleague, Judge Alex Kozinski, a Republican-appointed libertarian and the presiding judge in Baca’s appeal, who has lately seized the spotlight with his savage takedowns of the law in dark-humored and compulsively readable articles and opinions. In a recent, widely circulated law review article, he went so far as to demand AEDPA’s repeal, calling it “a cruel, unjust and unnecessary law that effectively removes federal judges as safeguards against miscarriages of justice.”

Federal judges like Reinhardt and Kozinski can only be removed from office by impeachment and not for any reason relating to their legal decisions. Federal judges are thus uniquely positioned to stand as the last bulwark against wrongful convictions. And yet they must follow the law. As long as AEDPA stands, a federal judge’s power to reverse a state-sanctioned conviction is severely limited—even if that conviction rests on a foundation of perjured testimony and suppressed evidence. Severely limited, that is, unless a judge can find a way to convince a prosecutor to change his mind.

* * *

Kozinski presided over Baca’s oral argument with his colleagues Kim Wardlaw and William Fletcher, both Clinton appointees. Standing before them, Baca’s attorney, Patrick Hennessey Jr., emphasized the magnitude of the misconduct: Spira and Melendez’s lies about the informant receiving no benefits in exchange for his testimony and Vinegrad’s presentation of those lies as truth. But the judges steered the conversation to AEDPA, where the case promptly bogged down. It was not enough that Baca’s trial was infected by perjury and prosecutorial misconduct, the judges reminded Hennessey. He had to show that the state court’s decision to convict Baca was not just wrong but wrong without any reasonable justification. When Hennessey took his seat, there was little indication he had succeeded in that effort.

Because the case was now in federal court, the local district attorney had handed the reins to the state attorney general’s office, represented by Deputy Attorney General Kevin R. Vienna. When it was his turn to speak, the atmosphere changed abruptly. Vienna had scarcely opened his mouth when Judge Fletcher broke in, “Do you concede that Mr. Spira lied on the stand?”

“I don’t, I–I–I am not certain that he lied,” Vienna stammered in response.

Judge Kozinksi demanded to know whether Spira or Vinegrad had been prosecuted or disciplined in any way for their actions in the Baca prosecution. Vienna said no. “They’re going to keep doing it,” Kozinski said. “Because they have state judges who are willing to look the other way.”

Vienna tried to respond, but Kozinski cut him off. “It’s not a reassuring picture,” he said. After more back and forth, Judge Kozinski added, “It would look terrible in an opinion when we—when we write it up and name names.” Vienna stammered, “That uh, uh,” Kozinski cut him off again, “Would your name be on there?”

To an appellate lawyer who argues before the 9th Circuit, the threat was anything but veiled: Kozinski was promising to make an example not just of the prosecutors in the Baca case but of Vienna as well. He’d done it before. In United States v. Kojayan, a 1993 opinion that has since become required reading at many law schools, Kozinski lambasted a federal prosecutor for grossly and repeatedly misrepresenting key facts to defense counsel and the jury. Kozinski called out the prosecutor a total of 49 times, all but ensuring that his name would become synonymous with the tainted case. So potentially ruinous was the Kojayan opinion that the U.S. Attorney’s office pleaded with Kozinski to revise it to excise the personal shaming of the government’s lawyer. Kozinski eventually relented. There was no guarantee the clearly irate judge would be so lenient this time around.

Shame has long played a role in criminal cases in the United States, but it is a history of shaming offenders, not the supposedly righteous people who accuse them. In the colonial era, we put guilty people in the stocks and pelted them with rotten fruit. We branded them like cattle. We maimed them. These rituals of public shaming were designed to exact retribution, deter future misdeeds, and impress upon the wrongdoer the steep price of deviating from community norms. In deploying this ages-old shaming sanction, Kozinski was taking a familiar judicial tactic and giving it a wholly unexpected twist.

After a series of increasingly fraught exchanges, Judge Kozinski gave Vienna his terms. “Talk to the attorney general and make sure she understands the gravity of the situation,” he said. “And understand that we take it very seriously.” Vienna’s office, led by Kamala Harris, a rising political star in the Democratic Party, would be wise to “work out something” and to avoid having the 9th Circuit decide the case. Win or lose, he told Vienna, “I don’t think an opinion is something that is gonna be very pretty.”

* * *

Why do state court judges uphold convictions that are riddled with misconduct? Why do state prosecutors insist on defending them? The answer, according to Northeastern University law professor Daniel Medwed, who has written extensively on the topic, is likely a combination of law, politics, and basic human psychology.

Our criminal justice famously presumes that every accused person is innocent until proven guilty. But once a conviction is obtained, that presumption is turned on its head. Charges were brought, and a jury, which saw evidence and heard from the witnesses firsthand, voted to convict. At that point, finality sets in.

Prosecutors tasked with defending a conviction against compelling evidence that it was wrongfully secured typically have two choices. They can accept the responsibility for participating—directly or indirectly—in an injustice, or they can insist that nothing went awry or that whatever mistakes may have been made were “immaterial”—that is, the jury would have convicted anyway. The justice system strongly pushes them in the latter direction. Ambitious, hard-charging prosecutors know that the way to the top is amassing guilty verdicts, not admitting mistakes. In 47 states, their bosses—the county district attorney, the state’s attorney general—are elected. Incompetence, or appearing “soft on crime,” can be fatal at the ballot box.

As the Baca case shows, the refusal to admit a mistake—or even an act of bad faith—holds true regardless of whether the prosecutor defending the conviction had any involvement at the trial level, personally knew the key players, or even worked in the same office. Vienna himself had no connection to Vinegrad or Spira, and yet he did his level best to defend them. This may be due, in part, to a phenomenon that Medwed calls “the conformity effect.” Prosecutors like Vienna, he writes, are “culturally aligned with that side and tend to defer to their peers who were the original decision makers.”

It’s not just the prosecutors whose bias is toward the original decision. Like most top prosecutors, the majority of state court judges are elected. To keep their jobs, state court judges may feel they must uphold convictions or sentences, even ones obtained in blatant violation of the defendant’s constitutional rights. In California, where Baca was convicted, the governor appoints appellate court judges. But every 12 years, they must stand for retention elections, which are not always rubber stamps. Last week, the Republican-controlled legislature in Kansas passed a bill allowing for the impeachment of “activist” judges. Conservative groups are determined to remake that state’s highest court by convincing voters to oust four of its seven justices in retention elections this November.

Like prosecutors, judges also have a vested interest in finality and the assumption that the system worked precisely as it was designed to do. The alternative is destabilizing and demoralizing. “Psychology,” Medwed says, “plays a huge part. Once there has been a decision, you tend to perceive the evidence from the lens of that decision. Judges after conviction as a matter of law are supposed to approach claims of wrongful conviction with great skepticism. Then you have the conformity effect—many judges are former prosecutors themselves—and political considerations. I very much doubt that most appellate judges are thinking during oral argument, ‘Oh my Gosh, if I grant this petition, I will not be retained.’ It is a more subtle influence. They have all these reasons not to reverse, legal reasons they can stand upon, which may be a little bit of a fig leaf for political and psychological bias.”

* * *

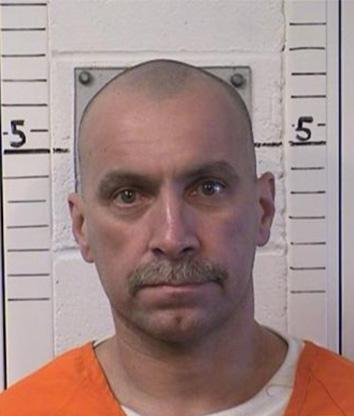

California Department of Corrections

Baca was not an easy defendant for either prosecutors or judges to rally around. One of the victims had arguably identified him as the shooter in a brutal double murder, and there was other incriminating evidence—in his own testimony, Baca placed himself at the scene on the day of the murders and admitted taking off in Mix’s car without his permission, although he claimed he left before the shootings. Questioning the integrity of Baca’s conviction, much less freeing him, could be seized upon as evidence that the court was unleashing a dangerous man into the community.

But the job of a judge is to enforce the Constitution, which often means arriving at a decision that is not politically popular or palatable to voters, who might well harbor an ends-justify-the-means mentality. Judge Wardlaw, one of the 9th Circuit judges presiding over Baca’s oral argument, was skeptical that the California justices had carried out their mandate. When Vienna tried to argue that the state judges “did not condone” what Spira and Vinegrad had done, Wardlaw replied, “No. That’s not clear. Because they out and out say this guy—the prosecutor—lied on the stand. And he, by his lies, bolstered the credibility of a jailhouse snitch.” And yet the state court judges insisted that the misconduct had no bearing on the integrity of the verdict. To Wardlaw, that was tantamount to condoning the behavior. “I understand why they do that,” she said “I mean, they’re elected judges. They’re not gonna be reversing these things.”

To some, this is as it should be. In a recent law review article, Harvie Wilkinson III, a distinguished, long-serving federal judge on the 4th Circuit, argued that the combination of appointed and elected judges “reflects a healthy ambivalence about judicial power.” Wilkinson is skeptical that “elected judges are ‘tougher on crime’ than are appointed judges” but added that even if that were true, “this merely begs the question of whether the tough stance is right or wrong, or whether it is illegitimate for judges to have some appreciation for the views and concerns of the larger public.”

The 9th Circuit panel that presided over Baca’s case clearly hewed to a different philosophy. And because the oral argument was readily available for online viewing—and because Kozinski’s colorful personality and lacerating wit have made him a celebrity in the legal world, the case quickly became a sensation. Kozinski’s evisceration of Vinegrad and Spira and his unconcealed distaste for the California attorney general’s office’s staunch defense of a conviction obtained through perjury, was widely circulated among lawyers and judges. (To date, the video has been viewed more than 31,000 times on YouTube—in the legal realm, the equivalent of going viral.) The Los Angeles Times picked up the story, in an article titled, “U.S. Judges See ‘Epidemic’ of Prosecutorial Misconduct in State.”

The impact of the attention was profound. As instructed by Kozinski, Vienna brought the matter to his boss’ attention, and Harris, now running for the U.S. Senate, authorized a stunning about-face. Less than three weeks after oral argument, Vienna filed a motion with the 9th Circuit, which stated, in part, “After oral argument, the matter was discussed with the Attorney General and the new Riverside County District Attorney. In the interests of justice, the People have concluded that the conviction should be set aside. Therefore, in behalf of the state, the Attorney General asks this Court for summary reversal.” Baca remains in custody, awaiting a retrial. Writing about Baca’s case some months later, Judge Kozinski commented, “Naming names and taking prosecutors to task for misbehavior can have magical qualities in assuring compliance with constitutional rights.”

* * *

Kozinski has continued naming names. Last month, an 11-judge panel of the 9th Circuit turned down a prisoner’s request for a new trial on the grounds of extreme prosecutorial misconduct. The court cited the constraints of AEDPA and the overwhelming evidence of guilt. But Kozinski, who wrote the majority opinion, devoted an entire section to detailing the misdeeds of two Seattle prosecutors. He concluded by recommending that the prosecutors present themselves to the state bar, opinion in hand, and offer an explanation if they wished “to clear their names.”

Can other federal judges follow Kozinski’s lead? The answer may depend on how many people are paying attention. In 1999, George Gage, a 60-year-old electrician with no criminal record, was charged in Los Angeles Superior Court with multiple counts of raping and sexually abusing his stepdaughter, Marian, when she was a young girl. Marian made the allegations years later; other than her accusations, there was no evidence that the crimes had occurred. Twice, Gage turned down favorable plea offers. “I am not a sexual offender,” he said.

In closing argument, the prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Christopher Estes, told the jury that the case boiled down to Marian’s credibility. “If you believe what [Marian] said is to be the truth,” he said, “then you know that each and every element of these charges has been satisfied.” At the time Estes was prosecuting Gage, he was also running for election to be a judge on the California Superior Court. On March 2, 2000, the jury convicted Gage on all counts. On March 7, 2000, Estes won the election.

At sentencing, after a protracted dispute, the presiding judge obtained Marian’s medical and psychological records, which Estes had never turned over to Gage’s lawyer. After reviewing them privately, the judge granted Gage a new trial, finding that the failure to provide Gage’s attorney with this evidence violated his right to a fair trial. Had the jurors known the full story, the judge concluded, they would likely have harbored grave doubts about Marian, whom the judge called “deranged” and “not candid with law enforcement, the district attorney’s office, or with the court or jury.” In a year of therapy after a suicide attempt, Marian made a single passing reference to sexual abuse, a silence the judge found “very inconsistent with the almost vomitus delivery of the morbid details of abuse the victim happily laid out at trial.” Also included in the trove of documents was this damning description by Marian’s mother: “A pathological liar who lives her lies.” The judge responded: “Mom ought to know. She has lived with [Marian] her entire life.”

The California Court of Appeals concluded that the trial judge had overstepped her authority in considering any of this evidence because it had never been presented to the jury. Gage’s conviction was upheld, and he was sentenced to die in prison. Fifteen years later, in 2015, when Gage’s case finally reached the 9th Circuit, AEDPA essentially mandated that the state court’s ruling be upheld. The federal judges, led by George W. Bush appointee Richard Clifton, were outraged, and subjected the deputy attorney general, David Cook, to a grilling that was similar in tone and substance to what Vienna experienced in the Baca case.

After being pressed repeatedly to explain why Gage’s rights had not been violated, Cook reminded the federal judges that the law required them to assume that the state appellate court decided the case correctly. Clifton was not persuaded. “I gotta say it doesn’t give me a lot of confidence in the verdict.” There was a long pause as Cook, clearly uncomfortable, stared down at the lectern. Judge Clifton pressed, “Does it give you a lot of confidence in the verdict?” Cook started to respond that it was not his place to question the verdict, but again Judge Clifton cut him off. “On some level you are,” Clifton said. The prosecutor’s job, he said is “not simply to obtain convictions, it’s to do justice.”

*Correction, April 8, 2016: Due to a photo provider error, a caption in this article originally misidentified the middle initial in the name of the courthouse in the photo of Judge Alex Kozinski. It is the James R. Browning courthouse.

Clifton and his colleagues sent the parties to a mediator to try to work out a fair resolution. But the mediation was unsuccessful and the California attorney general’s office refused to do for Gage what it had done for Baca. Cook was visibly embarrassed before the three-judge panel, but the lack of media attention meant that his superiors—including Attorney General Kamala Harris—did not feel the same pressure to confront any long-term reputational repercussions. The prosecutors simply refused to vacate the conviction or otherwise settle the case, knowing that the law was on their side. They were right. The case quietly went away.