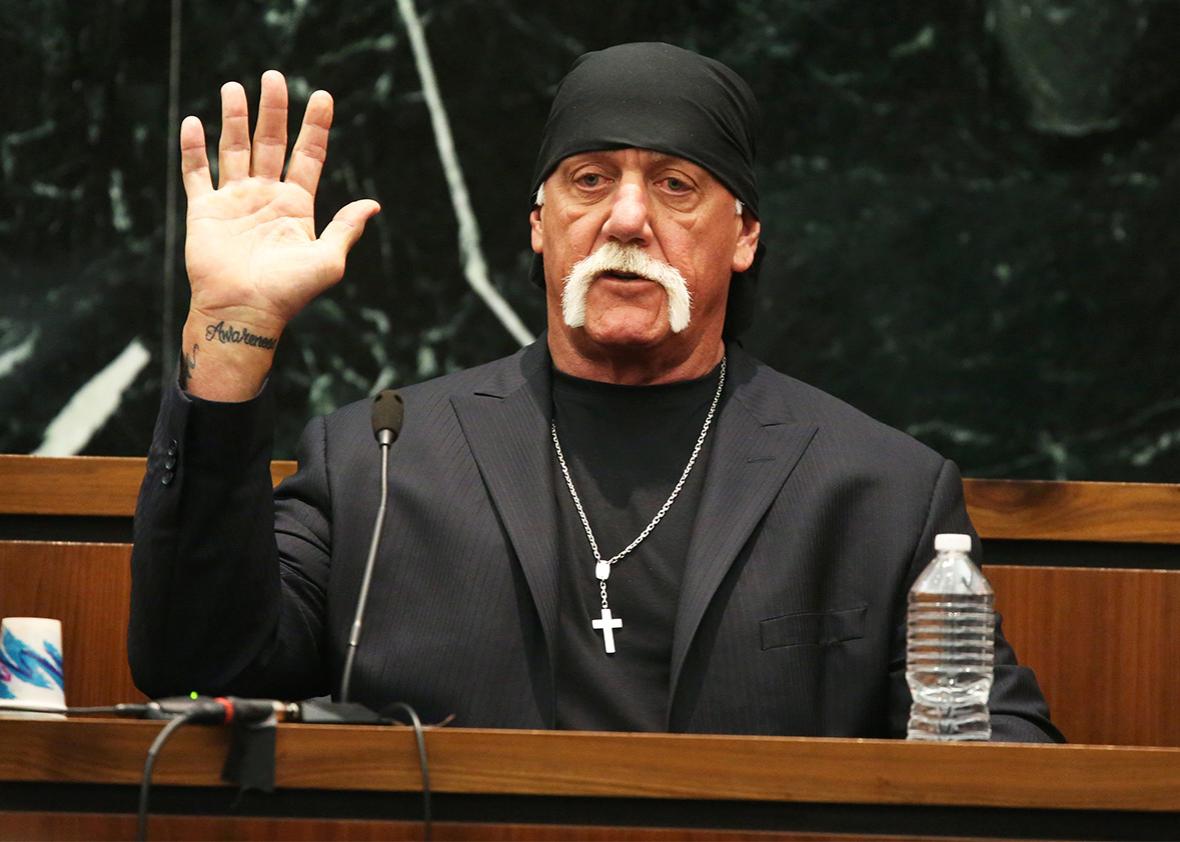

On Friday a Florida jury awarded Terry Bollea, better known as Hulk Hogan, more than $100 million in damages for Gawker’s publication of his sex tape. The jury’s decision valued Hogan’s right to privacy over the freedom of the press. Gawker publisher Nick Denton said prior to the trial that he expects his free-speech case would be a slam dunk on appeal, no matter what a rural Florida jury decided. After all, courts have traditionally given great deference to journalists to determine for themselves what is newsworthy and what isn’t.

But Denton may not be correct about deferential treatment this time. Some threads in modern law suggest that these jurors may not be alone in giving new deference to privacy concerns. And they may one day have the Supreme Court with them.

Let’s start with one of the privacy-related torts that Bollea sued under, Publicity Given to Private Life. It’s basically a legal punishment for publishers of nasty gossip. In order to win such a claim, the plaintiff must prove the offensiveness of the truthful revelation, in this case video footage of Bollea having sex, and also that it was not newsworthy. Punishment for this sort of truthful speech is a legal idea that’s been around since the 1800s.

Newsworthiness is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. The Restatement of Torts, a scholarly work written in the 1970s and considered by many courts to be persuasive authority in privacy cases, suggests that news is a category that includes crimes, arrests, drug deaths, rare diseases, wild animal escapes, children giving birth, “and many other similar matters of genuine, even if more or less deplorable, popular appeal.”

That’s an expansive definition, one that is potentially troubling in an Internet age when the distance between a journalist and a person with a social media account is shrinking—and when some private individuals publish deplorable stuff that appeals to many. But the Restatement also suggests that newsworthy information stops at “morbid and sensational prying into private lives for its own sake, with which a reasonable member of the public, with decent standards, would say that he had no concern.” Non-newsworthy information in their estimation would include the revelation of humiliating illnesses, private home life, and income tax returns.

There is also language that directly addresses the question of sex. “There may be some intimate details of her life, such as sexual relations,” the Restatement reads, “which even the actress is entitled to keep to herself.” The Restatement also suggests, however, that once a person subjects his work to public judgment, he has no right of privacy, “since these are no longer his private affairs.” This is essentially what Gawker argued in the case—that Hogan made his sexual life public when he discussed it in public forums. But the Restatement authors seem to recognize a difference between general talk and actual depictions. “Every individual has some phases of his life and his activities … that he does not expose to the public eye,” the Restatement reads. “Sexual relations, for example are normally entirely private matters.”

The confusing and subjective line between publishing something “deplorably appealing” and engaging in “sensational prying” is why courts hearing privacy-relevant lawsuits have been hesitant to second-guess journalists. Older court rulings somewhat routinely suggested that publishers themselves should be the ones to decide what is newsworthy. When some argue that media has the right to publish what it would like regarding public figures, they base that argument on this line of jurisprudence. But there are two problems for a free press hoping to rely on these precedents. One is that they may be changing. The other is that even those supporting publishers are very narrowly drawn.

Some courts have taken the changing technological landscape and an increasingly push-the-envelope media as occasions to decide that privacy wins. In 2007, for example, the Ohio Supreme Court embraced a previously rejected privacy tort in a case that didn’t involve media at all but a neighbors’ dispute over vandalism in which one published leaflets about the incident. In that ruling, the court suggested specifically that it needed to recognize the privacy tort because of troubling Internet-based publication decisions. “Today … the barriers to generating publicity are slight, and the ethical standards regarding the acceptability of certain discourse have been lowered,” the court wrote. “As the ability to do harm has grown, so must the law’s ability to protect the innocent.”

And the trouble for media is furthered because the U.S. Supreme Court has never decided precisely where privacy trumps a free press. There are key cases from years ago that suggest that the media has the right to publish truthful information gathered from police reports and in court, but each of these cases has been decided narrowly and the court has written as much.

Bartnicki v. Vopper, probably the most instructive recent Supreme Court precedent, was a case decided by the justices 6-to-3 in 2001. There, a radio station broadcast a surreptitiously recorded cellphone call, in which a teachers’ union negotiator seemingly discussed the possible use of violence to influence a school board response. The court found the revelation decidedly newsworthy enough to trump the callers’ privacy.

Even so, the justices quoted an earlier, limiting opinion: “We continue to believe that the sensitivity and significance of the interests presented in clashes between [the] First Amendment and privacy rights counsel relying on limited principles that sweep no more broadly than the appropriate context of the instant case.” In doing so, the justices quite literally refused to draw the line between press freedom and privacy.

That’s why the case involving Hulk Hogan and Gawker is an important one. If it ever finds its way to the Supreme Court, it will give the justices an opportunity to at least begin to draw that press-privacy line.

And, according to the Supreme Court’s own voting history, a sex tape might well be ruled private. Although Bartnicki upheld a speech claim, two concurring justices took care to note, in reference to an earlier case involving celebrity Pamela Anderson, that the “broadcast of [a] videotape recording of sexual relations between [a] famous actress and [a] rock star [is] not a matter of legitimate public concern,” suggesting that the tape was a “truly private matter.” “[T]he Constitution,” the justices wrote at the end of the concurrence, “permits legislatures to respond flexibly to the challenges future technology may pose to the individual’s interest in basic personal privacy.” In citing a case involving an actress known in part for her sexuality and nude photographs, the two concurring justices lay some groundwork for future justices to reject Gawker’s argument that Hulk Hogan’s openness about his sex life made the sex tape newsworthy.

Moreover, that concurring opinion in Bartnicki suggests that the court at that time might have decided in favor of Hulk Hogan’s privacy. In addition to the two concurring justices noted above, the three who dissented cited worries about the invasive nature of technology and the need for greater privacy. “We are placed in the uncomfortable position of not knowing who might have access to our personal and business emails, our medical and financial records, or our cordless and cellular phone conversations,” they wrote. In a case involving a celebrity sex tape, they might well have joined the two who wrote specifically about such an item’s lack of newsworthiness. Which suggests that a majority of the court—at least 5-4—might have found that a celebrity whose sex tape was published against his will could constitutionally win a privacy claim against a publisher.

That’s why it’s possible that the Supreme Court would agree with the jurors in the Hulk Hogan trial, and why publishers should not take their ability to determine newsworthiness for granted. It’s true that the justices have changed in the past 15 years (of the five who would seem to lean toward privacy on the issue of sex tapes in Bartnicki, only two, Stephen Breyer and Clarence Thomas, remain on the court) and that times have changed as well. But as late as 2014, the court recognized and protected “the privacies of life” contained in cellphones. The search-and-seizure case didn’t involve a publisher, but did involve police interception of photographs and video from the phones. “Today,” the court wrote, “it is no exaggeration to say that many of the more than 90 percent of American adults who own a cell phone keep on their person a digital record of nearly every aspect of their lives—from the mundane to the intimate.” The justices voted unanimously to keep those privacies out of police hands without a warrant.

We may someday get to find out whether such privacies can be kept off the Internet as well.

Disclosure: Two Slate editors have spouses involved in this case. One was a witness for Gawker. The other was a lawyer for Gawker. Neither editor worked on this piece.