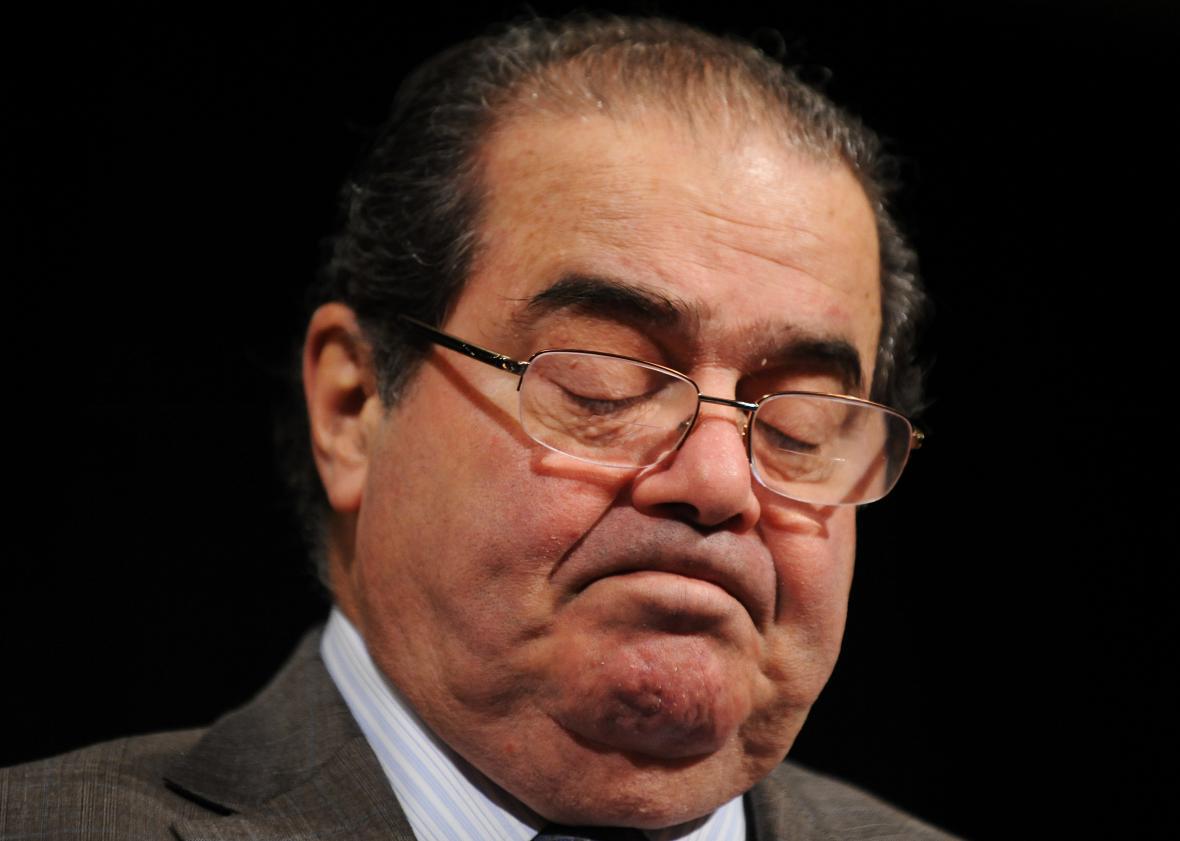

Justice Antonin Scalia, who died over the weekend at 79, was the most colorful Supreme Court justice of recent memory. He liked to break open the thesaurus and harangue his colleagues with obscure insults, calling their work product “legalistic argle-bargle” in one memorable dissent. He wrote well and, in off-the-radar-opinions on politically obscure but important legal questions, he often out-analyzed his colleagues. On the bigger questions, however, his legacy is murky.

Scalia was a reliable vote on the right side of the spectrum, but he frequently found himself in dissent, despite serving on a court staffed mostly by Republican-appointed justices during his entire career. Conservatives will forever be grateful for his role in securing gun rights in District of Columbia v. Heller and blocking campaign finance reform in Citizens United and other major cases. But he failed to stop the same-sex marriage juggernaut (his Republican colleague Justice Anthony Kennedy defected) or Obamacare (Chief Justice John Roberts absconded), to eliminate abortion rights, or to defeat affirmative action. These were all issues close to his heart and of great importance to the conservative legal movement. These defeats will forever mar his legacy of success as a conservative champion.

Some of Scalia’s seemingly rightward moves actually backfired. Early in his career, Scalia joined or defended a series of legal opinions that strengthened executive power. At the time, conservatives saw the powerful executive, under the leadership of President Ronald Reagan, as a bulwark against an out-of-control bureaucracy that was egged on by congressional barons. But what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. The pro-executive jurisprudence of the court has helped President Barack Obama advance his regulatory agenda, which conservatives have taken to calling executive overreach and a violation of constitutional principles.

Scalia is most famous for championing the judicial philosophy of originalism, which says that the Supreme Court should interpret the Constitution as it was understood at the time of its ratification (or at the ratification of individual amendments). He worked tirelessly to persuade his colleagues and the legal community that originalism was the only proper mode of constitutional decision-making. In Heller, he achieved a victory of sorts: Both he and Justice John Paul Stevens, who wrote the dissent, relied heavily on sources from the founding era. But even here, there is less than meets the eye. Heller notwithstanding, Scalia failed to convert his colleagues.

Only Justice Clarence Thomas, who has become increasingly isolated, has tried to use originalism in a consistent way. The three other Republican-appointed justices—Roberts, Kennedy, and Samuel Alito—are not originalists, nor are the four justices appointed by Democratic presidents. These justices decide cases the way justices always have: by using whatever materials at hand—historical sources, yes, but also (and mainly) judicial precedents, common sense, general principles, political values, and so on—to generate outcomes that pretty reliably track their ideological priors.

Scalia argued that justices who committed themselves to originalism could not make such ideologically self-interested decisions. He cited himself as an example. He occasionally ruled in favor of criminal defendants and voted to strike down a statute that banned people from burning the American flag. He also upheld various liberal statutes. But no Supreme Court justice always rules in favor of the side that he sympathizes with. Sometimes your side has a hopelessly bad argument. Many Supreme Court justices have been political moderates, voting in ways that both pleased and displeased their ideological fellows. Scalia was a very conservative justice, by both modern and historical standards.

At the same time, it’s hard to even imagine most justices trying to persuade people that they decide cases “neutrally” by pointing out that they sometimes voted contrary to their personal preferences. I have never heard Justice Sonia Sotomayor (on the left) or Justice Alito (on the right) say such a thing. Most justices vote however they vote and leave it at that. They seem pretty proud to be called liberal or conservative; their ideologies are part of their judicial identity.

In this respect, Justice Scalia really was different from the other justices. He considered himself a conservative but denied that he ruled conservatively. While the other justices ritualistically denied that politics should play a role in their decision-making, only he really meant it—or at least seemed to. His anguished complaints that other justices voted ideologically were met with puzzled silence. Of course, they voted ideologically; what else would they do? The stridency with which Scalia attacked them, especially in his later years, could only make one scratch one’s head. If he was the boy who revealed that the emperor wore no clothes, did he not know that he was also naked?

Scalia refused to acknowledge that originalism does not enable justices to decide cases neutrally. If they choose to adopt this methodology, and manage to figure out a way to make it constrain them, they are committed to enforcing mostly 18th-century values—which are, by definition, conservative.

In fact, the historical sources are rarely clear, and foundational questions about how originalism is supposed to proceed—including how much weight (if any) should be given to post-founding judicial precedents that deviate from the original understanding, and how broadly constitutional principles like “due process” and “equal protection” should be understood—are irresolvable. One of the original originalists—Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black—was a stalwart liberal. A liberal Yale law professor has mischievously proclaimed himself an originalist and shown how originalism can lead to liberal outcomes. Scalia’s interpretation of originalist sources has been frequently criticized, and in notable instances when he could not bend them to his will, he simply ignored them. His belief that campaign finance laws and commercial speech regulations violated the First Amendment would have surprised the founders, for example.

This is why originalism has no staying power except as a slogan. When Sen. Ted Cruz says that he will appoint an originalist if he wins the presidency, he means that he would appoint a justice who will vote to overturn Roe v. Wade and strike down economic regulation like Obamacare. Republican senators will block any nominee to the Supreme Court to replace Scalia who isn’t likely to vote in such a way—but neither President Obama nor a potential future liberal president would nominate such a person. The court is probably doomed to a lengthy period without a full slate of nine justices (at least through the election, possibly longer), which will be devastating to its effectiveness.

And damaging to its reputation as well, which has been in decline. It doesn’t take much imagination to see Scalia’s belligerent insistence that nearly every other justice on the court is politically motivated, even as he flamboyantly identified himself with the political right, as a factor in that decline. This is the tragedy of Justice Scalia. He thought he could remove politics from the Supreme Court, but he only made them worse.

See more of Slate’s coverage of Antonin Scalia.