With Justice Antonin Scalia’s sudden death earlier this month, the Supreme Court has gone from a sleeper issue in the 2016 election to the only issue. Democrats are trying to make political hay of Republicans’ unprecedented obstructionism. Mitch McConnell said again on Tuesday that there will be no confirmation hearing for any nominee until after November’s election, and Republicans on the Judiciary Committee also reiterated that there will be no hearing and no vote. Nothing has changed, then, since Harry Reid warned in the Washington Post last week, “If Republicans proceed, they will ensure that this Republican majority is remembered as the most nakedly partisan, obstructionist and irresponsible majority in history.”

It’s become an article of faith that Congress—and in turn, the voters casting ballots this November—has the ultimate say in deciding what happens to Scalia’s spot on the court. As Jeffrey Toobin has put it, “McConnell has the power to protect the Scalia seat, and he is doing it, at least until the next election. It is thus clearer than ever that the future of the judiciary is decided at the ballot box, not in the courtroom.”

The need for electoral action will feel more urgent if the Supreme Court’s much-touted term of the century—including pending cases on abortion, affirmative action, religious liberty, voting rights, and funding for public sector unions—ends in a raft of confusing 4-4 ties. A series of ties would be disastrous in a term full of landmark cases. The practical effect would be that while the lower court decision stands in that jurisdiction, the new rule doesn’t apply throughout the country. The decision has no precedential value, and you may end up with a crazy quilt of constitutional law. That should scare voters!

The problem with this hypothetical is that it assumes the Supreme Court will glumly play along, showcasing their institutional paralysis and despair. In the days since Scalia’s death, there’s been a lot of assuming that the remaining justices will hear a series of big-ticket cases they cannot agree on, split votes dutifully along 4-4 lines, write angry dissents, and more or less perform a Still Life in Dysfunction for the next four months.

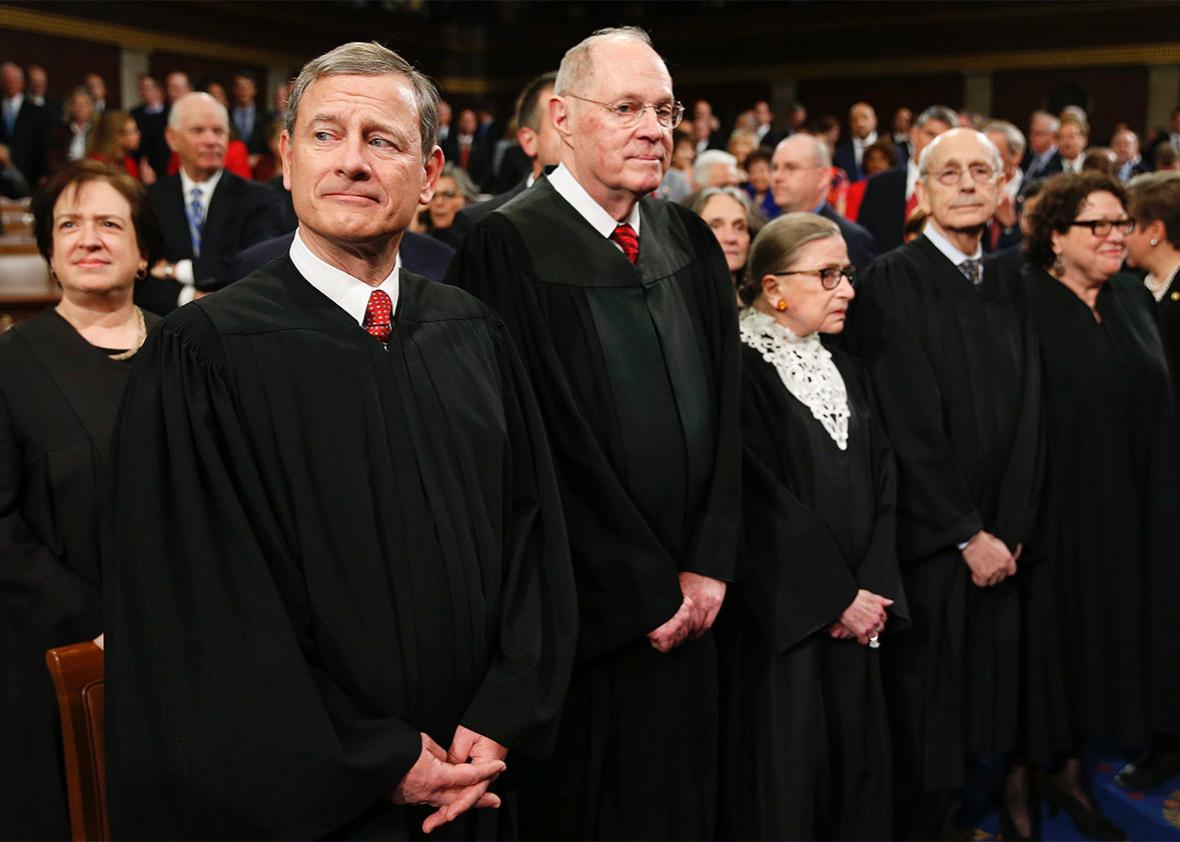

That may still happen, but it’s not the most likely outcome. As several astute court-watchers have already observed, Chief Justice John Roberts is nobody’s Exhibit A, and he has the ability to control and guide the high court in ways that may avoid the kind of public trainwreck that Democrats are hoping for. As Garrett Epps pointed out in the Atlantic late last week:

[A]s the historically wise journalist Lyle Denniston pointed out to me, history suggests that the justices will strive to avoid deadlock. Split courts have often set key questions aside for reargument in the coming term. (In 1985, for example, Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. missed a third of the arguments for health reasons; the Court held three cases to reargue when he was back on the bench.) And, in the past, seemingly polarized justices have crossed over to forge narrow results, deciding specific cases while leaving larger issues for another day.

Tom Goldstein of SCOTUSblog made the same observation immediately after Scalia’s death: “I previously wrote that cases in which the Supreme Court is divided four to four after Justice Scalia’s death would be ‘affirmed by an equally divided Court.’ I now believe that is wrong.” Goldstein went on to note that “there is historical precedent for this circumstance that points to the Court ordering the cases reargued once a new Justice is confirmed.” Holding cases over for reargument next term only works if there are hearings and a vote this summer. But even if they cannot order reargument, there’s always the option of deciding the closely fought, closely watched cases on narrow technical grounds this year, and waiting for them to trickle back to the high court after Scalia’s seat is filled.

This is where John Roberts may come in. If anything matters as much to the chief justice as his own ideology, it’s institutional appearances. There is nothing Roberts hates more than public attempts to play political football with his court, regardless of which side is lobbing the ball. In a speech in Nebraska last year, Roberts talked openly about the ruptured state of affairs in Washington, noting that the “partisan rancor” of Congress “impedes their ability to carry out their functions.” He fretted, “I don’t want this to spill over and affect us.” As recently as Feb. 3, the chief justice (now presciently) told an audience at a New England Law | Boston event: “We don’t work as Democrats or Republicans, and I think it’s a very unfortunate perception that the public might get from the confirmation process.”*

Roberts has also long devoted his energy to propounding the idea that the role of the courts should be limited and constrained, which flies in the face of all the current rhetoric about the court as the ultimate decider of all vital issues. In addition to being Ted Cruz’s personal poster boy for all things bad and horrible, I can’t imagine Roberts wants his court to become the 2016 symbol of the most important and partisan branch of government.

So you can rest assured that Roberts, as well as his seven remaining colleagues, would hate being at the center of the 2016 election almost as much as they’d dislike moderating or narrowing any one vote in a close case. I suspect that fears that the term will end with a vast, paralyzing 4-4 thump are likely overblown. The question is how the court will avoid those angry deadlocks.

Maybe, says Simon Lazarus in the New Republic, Roberts will temper some of his own votes to avoid the appearance of politicization, as he has done in the past. Or maybe, says Jill Filipovic in Cosmopolitan, Anthony Kennedy now has cover to strike down the Texas abortion restrictions since that case has no precedential value. Either way, watch for a muted end of the term rather than the expected fireworks. As Epps concludes, “the current Republican tantrum may change minds inside the marble palace; it may do more to break a Republican ‘bloc’ than Barack Obama ever could.”

This puts Roberts on a paradoxical collision course with President Obama, a course some have argued they have been on for a decade. The former will be determined to prove that there is nothing going on right now that the court cannot handle, while the president and the Democrats will bank on the fact that open gridlock and paralysis at the court will illuminate the fundamentally nihilist worldview of the GOP obstructionists in the Senate. And it may place the president in the unenviable position of having to argue that, despite the fact that it appears to be bumping along quite nicely, the court is in fact barely functioning, and it’s all Mitch McConnell’s fault. No Drama Obama may find a no-drama term very frustrating, but the president’s frustration would likely make John Roberts feel warm and fuzzy inside.

Maybe American voters won’t care all that much about what the court is doing when it comes time to vote in November. A lot can happen between now and then—including a nominee who doesn’t get a hearing—that may anger voters who otherwise don’t care about affirmative action or abortion or unions. Polls already show clear public support for holding hearings. A new Pew poll shows that Americans favor having the Senate act on an Obama nominee by a margin of 56 percent to 38 percent. A Public Policy Polling survey released Monday showed similar results, particularly in swing states. Once a nominee is tapped—a real human with a name and a face and a story—those pro-hearing numbers are likely to bounce even higher.

But don’t look to the Supreme Court for signs of panic or dismay. Now more than ever, the justices will surely send signals that business goes on as usual, and that politics plays no role in any of it. Perhaps the ultimate paradox here is that the one justice who embraced the court’s position at the epicenter of political debate is not only gone from the court, but is the direct cause of what may be a quieter 2016 term than anyone could have expected.

*Correction, Feb. 24, 2016: Due to an editing error, this article originally misidentified New England Law | Boston as New England Law School. (Return.)