In addition to his fiery rhetoric, his originalism, and his profound impact on his fellow Supreme Court justices and the court itself, Antonin Scalia was famous for another thing: his surprising support of criminal defendants in many cases.

“I ought to be the darling of the criminal defense bar,” Scalia once pleaded. “I have defended criminal defendants’ rights—because they’re there in the original Constitution—to a greater degree than most judges have.”

If Scalia was a champion of those rights, he was an accidental champion, a jurist with a deeper objective—namely, fidelity to what he dubbed the “original meaning” reflected in the text of the Constitution—that happened to intersect with the interests of the accused at some points in the constellation of criminal law and procedure. Scalia is more easily remembered not as a champion of the little guy, the voiceless, and the downtrodden, but rather, as Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said, an “unwavering defender of the written Constitution.”

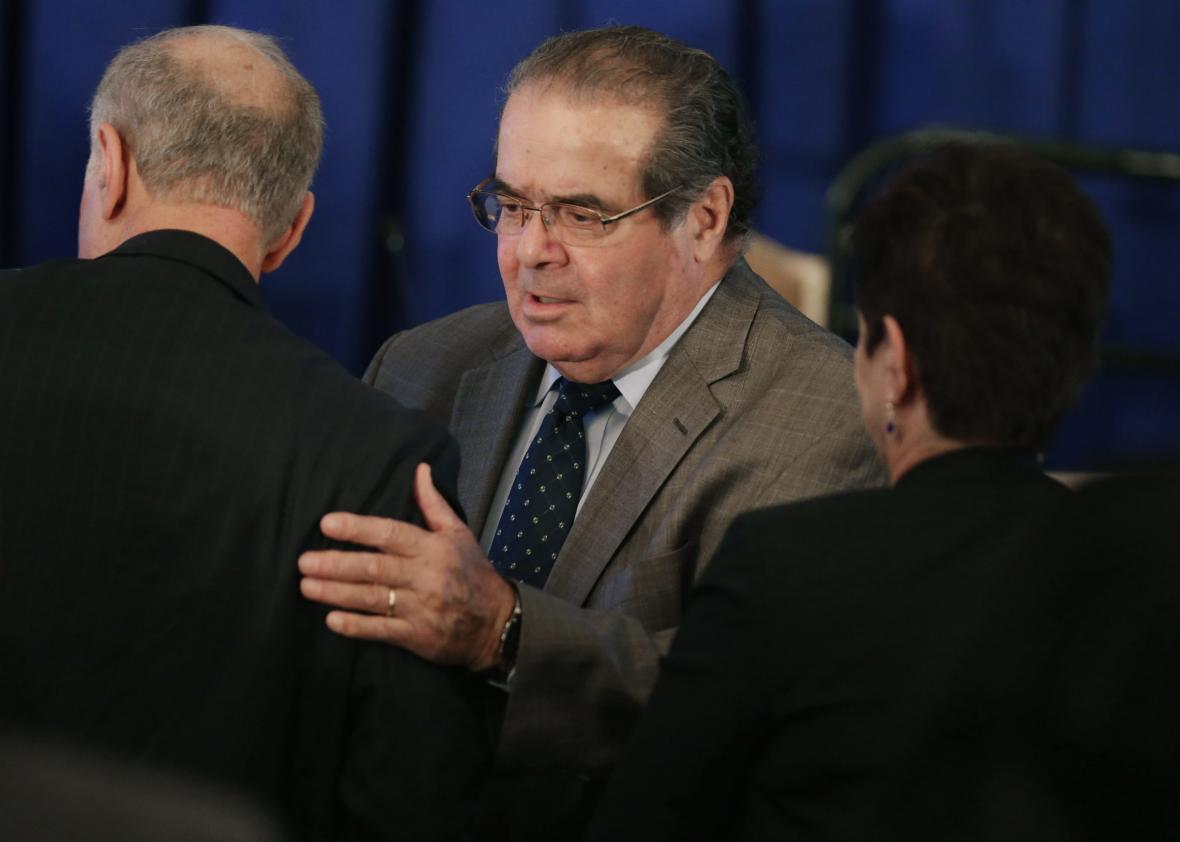

Still, Scalia’s opinions for the court—and, as ferociously, his dissents—have shaped the landscape of protections afforded to criminal defendants. Charles Ogletree, a famed public defender, adviser to President Obama, and Harvard Law School professor, said of Scalia, a brilliant, colorful, towering giant of the legal community who died suddenly on Saturday at the age of 79, “We are from different worlds, but we both appreciate the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.” Here are the myriad ways in which Scalia treated the founding document as protections against overzealous police investigations, intrusions on the right of the accused to examine witnesses at trial, and attacks on the right to a jury trial.

Protections From Unreasonable Searches and Seizures

Scalia wrote several opinions vigorously protecting the Fourth Amendment. “Justice Scalia actually believed that a group of revolutionaries cared deeply about privacy,” says Richard Myers, a law professor and former federal prosecutor. Scalia’s Fourth Amendment opinions, Myers added, illustrate that while “he did not believe in a living Constitution, he believed in a powerful, binding one.” For example, in Kyllo v. United States, the court held that the use of a thermal-imaging device to keep tabs on a private home is a Fourth Amendment search.

The government argued that no search of the home occurred because the thermo-imaging device captured “only heat radiating from the external surface of the house.” Scalia, however, in his opinion for the court, was having none of it: “But just as a thermal imager captures only heat emanating from a house, so also a powerful directional microphone picks up only sound emanating from a house—and a satellite capable of scanning from many miles away would pick up only visible light emanating from a house.”

More than a decade later, in Jones v. United States, the court, with Scalia again at the helm, held that the government violated the prohibition against unreasonable searches and seizures when it placed a GPS device on a suspected drug dealer’s car and tracked the vehicle’s movements for nearly a month. The prosecution argued that the defendant did not have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” on public roads. Scalia focused on the particular concern for government trespass on “persons, houses, papers, and effects” at the time of the drafting of the Constitution to strike down the search.

Scalia also was strong in dissent when a majority of the court disagreed with his Fourth Amendment views. In a 2014 case, Navarette v. California, the court held that the Fourth Amendment tolerated a warrantless traffic stop where the officers said they stopped the truck because it “matched the description of a vehicle that a 911 caller had recently reported as having run her off the road” and “as the two officers approached the truck, they smelled marijuana.” Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the court, concluded “under the totality of the circumstances, the officer had reasonable suspicion that the driver was intoxicated.” In a powerful dissent, Scalia referred to the logic of the court’s opinion as a “freedom-destroying cocktail” that provided law enforcement with more leeway in stopping motorists based on “anonymous claims.”

Scalia also dissented from the court’s recent decision in Maryland v. King, which affirmed against a Fourth Amendment challenge to the taking of a DNA sample from inside the mouth of a person as “part of a routine booking procedure for serious offenses.” Scalia wrote, “No matter the degree of invasiveness, suspicionless searches are never allowed if their principal end is ordinary crime-solving. … That prohibition is categorical and without exception; it lies at the very heart of the Fourth Amendment.” Scalia continued: “Today’s judgment will, to be sure, have the beneficial effect of solving more crimes; then again, so would the taking of DNA samples from anyone who flies on an airplane … , applies for a driver’s license, or attends a public school. Perhaps the construction of such a genetic panopticon is wise. But I doubt that the proud men who wrote the charter of our liberties would have been so eager to open their mouths for royal inspection.”

Taken together, these cases reflect not an expansion of the meaning or reach of the Fourth Amendment but rather a justice who, in the words of law professor, Fourth Amendment scholar, and former Supreme Court clerk Orin Kerr, “restored the status quo” on such issues. “[He] restored the government’s investigatory power to the level that existed at [the founding],” Kerr said. Scalia did not merely join the court’s progressive wing in these cases. In Kyllo, Justice John Paul Stevens joined the dissent. In both Navarette and King, Justice Stephen Breyer joined the majority. For Stevens and Breyer, it seems, the rebalancing of the relationship between government and the privacy of the people shifts based on changes in our mores—the biggest interruptions of the status quo being the influence of new technology on societal expectations of privacy. In this sense, then, Scalia’s approach often had the effect of maximizing, not contracting, individual liberty for not just defendants but for all people.

The Right to a Jury Trial and to Confront an Accuser

By any measure, Scalia ushered in a revolution in the court’s Sixth Amendment cases. In a recent tribute, professor Rachel Barkow, who called clerking for Scalia “one of the highlights of my life,” emphasized his outsized contribution to this area of law. As she wrote, Scalia was a “staunch advocate of the jury guarantee,” and his opinions “led to a sea change in modern sentencing practices.”

Barkow points to Scalia’s dissent in Maryland v. Craig, where he railed against the court for permitting “a child witness to testify via closed circuit television in a sex abuse case,” instead of requiring the child to testify live in the courtroom where she would be subjected to cross-examination by the defense. The Constitution, Scalia wrote, does not authorize judges to “conduct a cost-benefit analysis of clear and explicit constitutional guarantees, and then to adjust their meaning to comport with our findings.”

Later, in Crawford v. Washington, Scalia’s view that the historical understanding of the right to confrontation won the day. In the Crawford case, the prosecution “played for the jury” a witness’ “tape-recorded statement to the police describing the stabbing, even though he had no opportunity for cross-examination.”* The state court affirmed the conviction despite use of the tape because the “statement was reliable,” a logic that Scalia roundly rejected: “Dispensing with confrontation because testimony is obviously reliable is akin to dispensing with jury trial because a defendant is obviously guilty.”

In Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, Scalia, writing for the court, found that defendants had a right to confront lab technicians. When presented with the argument that the court should accommodate the “‘necessities of trial and the adversary process,” Scalia responded indignantly. “The Confrontation Clause—like those other constitutional provisions—is binding, and we may not disregard it at our convenience,” he wrote.

Scalia has similarly championed the right of the accused to have a jury, not a judge (“a lone government employee of the State,” in Scalia parlance), determine the facts that could lead to an increase in punishment. In 2000, in Apprendi v. New Jersey, the court decided a case in which a jury convicted the defendant of possessing a firearm for an unlawful purpose, which carried a maximum sentence of 10 years. The trial judge then unilaterally found that “in committing the crime [the defendant] acted with a purpose to intimidate an individual or group of individuals because of race, color, gender, handicap, religion, sexual orientation or ethnicity.” The hate crime finding increased Apprendi’s maximum sentence from 10 years to 20 years imprisonment. The court’s jurisprudence at the time permitted judges to decide “sentencing factors” even though the Sixth Amendment required jurors to find each element of the offense. Scalia, writing for the court, eviscerated the distinction between elements of the offense and sentencing factors that enhance the base level of punishment, writing that the Sixth Amendment requires a jury—not a judge—to find “any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum.”

In Arizona, even after the court’s decision in Apprendi, a judge—not a jury—found the existence of an aggravating factor in a murder case, which needs to be found in order to open the door for the death penalty. In Ring v. Arizona, decided two years after Apprendi, the court clarified that “capital defendants, no less than noncapital defendants” must receive a jury determination on factors that might increase their punishment. Scalia, in a separate concurrence, responded to the state’s assertion that aggravating factors should be treated differently than traditional elements of the offender’s case: “I believe that the fundamental meaning of the jury-trial guarantee of the Sixth Amendment is that all facts essential to imposition of the level of punishment that the defendant receives—whether the statute calls them elements of the offense, sentencing factors, or Mary Jane—must be found by the jury beyond a reasonable doubt.” He continued, powerfully, noting:

[O]ver the past 12 years the accelerating propensity of both state and federal legislatures to adopt “sentencing factors” determined by judges that increase punishment beyond what is authorized by the jury’s verdict, and my witnessing the belief of a near majority of my colleagues that this novel practice is perfectly OK, cause me to believe that our people’s traditional belief in the right of trial by jury is in perilous decline. That decline is bound to be confirmed, and indeed accelerated, by the repeated spectacle of a man’s going to his death because a judge found that an aggravating factor existed.

While Scalia’s opinions often benefited criminal defendants, he didn’t reflexively seek to benefit them. For example, in Hudson v. Michigan Scalia refused to apply the exclusionary rule protection against illegally obtained evidence entering jury trials to the failure of the police to “knock and announce” themselves before entering a home with a search warrant. Scalia has also decried a different court-created prophylactic rule, the so-called Miranda rule, which demands that police officers read defendants their rights at the time of arrest. He also had a notably spotty record on crime and racial bias claims. And the death penalty was where Scalia reserved his angriest rhetoric. “If there are justices that were the conscience of the court, then Scalia was its wrath,” said Lee Kovarsky, a law professor at the University of Maryland. “He used that voice to transform legal experiences into cultural ones, and capital punishment inspired his most weaponized prose.” Finally, and perhaps most damningly for his legacy: Scalia was not a friend to the plausibly innocent. He once called the death penalty an “enviable” result for two men—Leon Brown and Henry Lee McCollum—who were convicted of raping an 11-year old girl and killing her “by stuffing her panties down her throat.” DNA evidence later exonerated both men. When the court ordered a hearing to determine whether a man on Georgia’s death row was “actually innocent,” Scalia callously opposed the proceeding, finding “no sound basis for distinguishing an actual-innocence claim from any other claim that is alleged to have produced a wrongful conviction.” More than being committed to getting it right, “Justice Scalia was extraordinarily committed to preserving state determinations of criminal guilt, even in death penalty cases,” Kovarsky told me.

In the end, then, Scalia was neither the darling nor the devil of the criminal defense bar. The real-world moral impact of one’s decisions is a burden that a judge carries and cannot easily shake. People and things are torn apart, isolated, and brutalized because of the decisions that judges make. However, with Scalia, the text of the Constitution was sacred text, and the obligation that he strived to meet during his time on the bench was fidelity to the words as written. He could have done a lot better by criminal defendants, but he could have done a lot worse, too.

Correction, Feb. 16, 2016: This post originally misstated that the prosecution in Crawford v. Washington played a tape-recorded statement for the jury from the alleged victim of a stabbing. It was a statement from a witness in the case. (Return.)

See more of Slate’s coverage of Antonin Scalia.