When news of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s death at age 79 broke on Saturday afternoon, the partisan split over the justice’s legacy was immediately obvious. Some liberals were quick to use his death as an occasion to jeer Scalia’s tenure, largely dwelling on his vociferous opposition to minority rights. Meanwhile, conservatives mourned the loss of their greatest judicial advocate, lauding Scalia as a giant of constitutional law. That’s fine and fair: Scalia was a political lightning rod, repulsing Democrats as much as he beguiled Republicans. But as time goes on and the sharp partisan contours of his most famous rulings blur, I have little doubt that Scalia will be remembered as one of the truly great justices on the United States Supreme Court.

Liberals—and, as a shorthand, many journalists—labeled Scalia a “conservative.” That was true as far as political temperament went; from his notorious friendship with Dick Cheney to his thinly veiled delight at the outcome of Bush v. Gore, Scalia was a Republican at heart. But to call him nothing more than a “conservative” would be to overlook the remarkable nuance and complexity of his jurisprudence. Scalia cast a decisive vote in the most important free speech case of the 1980s, Texas v. Johnson, which held that flag burning qualified as constitutionally protected expression. He wrote the landmark majority opinion in 2011’s Brown v. EMA, a double victory for First Amendment advocates that protected both depictions of violence and minors’ rights. And he dissented in Maryland v. King, arguing that the Fourth Amendment forbids law enforcement from collecting DNA from arrestees. (His fierce dissent sounds like it could have sprung from the pen of Edward Snowden.)

Despite his King vote, Scalia was widely viewed by many Americans as a harshly law-and-order justice. Again, that label is simply inaccurate. In many contexts, Scalia was extraordinarily protective of Americans’ right to privacy—though he himself would never use that term. He wrote the majority opinion in Kyllo v. United States, a 5-4 ruling that barred police from peeping into a home with a thermal-imaging device. He also wrote the majority opinion in Florida v. Jardines (another 5-4 decision), barring police from entering private property with a drug-sniffing dog without a warrant. Time and time again, he cast votes to protect drivers from intrusive car searches by law enforcement. Just last term, he sided against the police in a landmark ruling that restored constitutional rights to motorists illegally detained by cops.

And then there’s his view of the Confrontation Clause, which guarantees every criminal defendant the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” The Framers of the Constitution intended the clause to forbid hearsay in the courtroom, allowing every defendant to cross-examine, under oath, those who offer testimonial evidence against him. Before Scalia joined the court, this crucial safeguard against faulty trial testimony had been reduced to a constitutional vestigial limb. As a justice, Scalia embarked on an astonishing and almost entirely successful crusade to restore the clause’s place in the pantheon of civil liberties. In a series of landmark rulings—many authored by Scalia himself—he endeavored to halt the trend of prosecutors introducing dubious hearsay evidence against defendants. This crusade often aligned the justice with unexpected allies, such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg (with whom he was great friends) and Sonia Sotomayor (with whom he was not). And just last term, Scalia took on his frequent ideological bedmate, Justice Samuel Alito, when he sensed Alito “shoveling … fresh dirt” on the newly restored right. The Confrontation Clause was Scalia’s fight; if he had to vote with Sotomayor or against Alito to reach the right result, so be it.

Any honest assessment of Scalia’s legacy, of course, must contend with his vehement opposition to the rights of historically oppressed groups—namely women’s rights (especially abortion) and gay rights. And yet reading over Scalia’s abortion dissents, it is difficult not to feel a twinge of respect for his consistent constitutional views. Nobody doubts that Scalia personally abhorred abortion. But his abortion opinions read less like the rants of an arch pro-lifer and more like the pained cries of a dedicated textualist who believed, as a matter of pragmatism and constitutional law, that such contentious issues can only be truly resolved by the democratic process. Here’s the despairing peroration of Scalia’s dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey:

There is a poignant aspect to today’s opinion. Its length, and what might be called its epic tone, suggest that its authors believe they are bringing to an end a troublesome era in the history of our Nation and of our Court. … [But] by foreclosing all democratic outlet for the deep passions this issue arouses, by banishing the issue from the political forum that gives all participants, even the losers, the satisfaction of a fair hearing and an honest fight, by continuing the imposition of a rigid national rule instead of allowing for regional differences, the Court merely prolongs and intensifies the anguish.

We should get out of this area, where we have no right to be, and where we do neither ourselves nor the country any good by remaining.

Scalia attempted to take the same let the people decide tack on gay rights—but admittedly, it’s harder to view Scalia’s gay rights dissents with cerebral esteem. Scalia’s apparent disdain for gay people bled into his first two gay rights opinions, which compared gays with drug dealers, prostitutes, and animal abusers. In his (still startling) dissent in Lawrence v. Texas, which invalidated Texas’ same-sex sodomy ban, Scalia accused the court of “largely sign[ing] on to the so-called homosexual agenda” and “tak[ing] sides in the culture war.” He wrote in defense of the “many Americans” who view homosexuality as “a lifestyle that they believe to be immoral and destructive” and championed their right to pass laws that strip gays of rights and benefits. The Constitution, Scalia insisted, permitted such raw legislative bigotry.

Plenty of people, myself included, have cited these passages as proof that Scalia was little more than a bitter homophobe. And even now, I’m confident Scalia’s anti-gay beliefs will remain as a lasting blotch on his legacy. But in a few decades—when a majority of Americans can’t remember a time when the Constitution did not guarantee gay people the same fundamental rights as heterosexuals—the sting of this rhetoric will dwindle. Scalia, after all, was writing in dissent; his words had little impact on the country. (Any impact they did have was surely positive: Scalia’s first gay marriage dissent accidentally expedited the invalidation of state-level same-sex marriage bans.) Memories of his regrettable prejudices will recede, and in their place will emerge the image of a titan of constitutional law, a deeply principled, sincerely dedicated man who devoted his life to the court he loved.

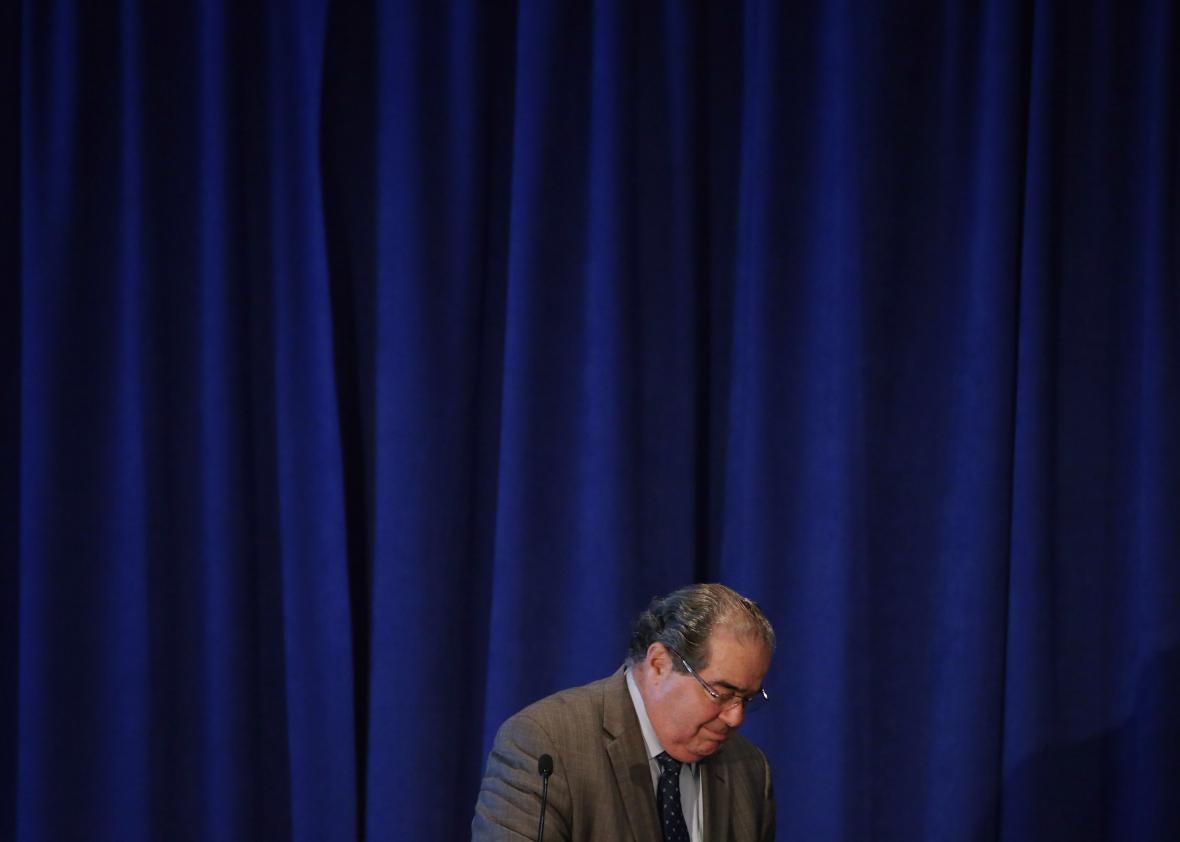

When I was younger and angrier, I expected to cheer Scalia’s retirement, elated by his absence from the court. Today, I only feel overwhelming sadness. In my time covering the court, I’ve grown to admire the gruff, cantankerous man who lobs bombs and quips at nervous lawyers and bemused justices alike. Scalia was the justice you either loved or hated, relentlessly opinionated, representative of everything that was right or wrong with the Supreme Court. He was witty, unpredictable, caustic, indignant, and brilliant. He was an American original. And after the partisan howling over his legacy fades, that is how his country will remember him.