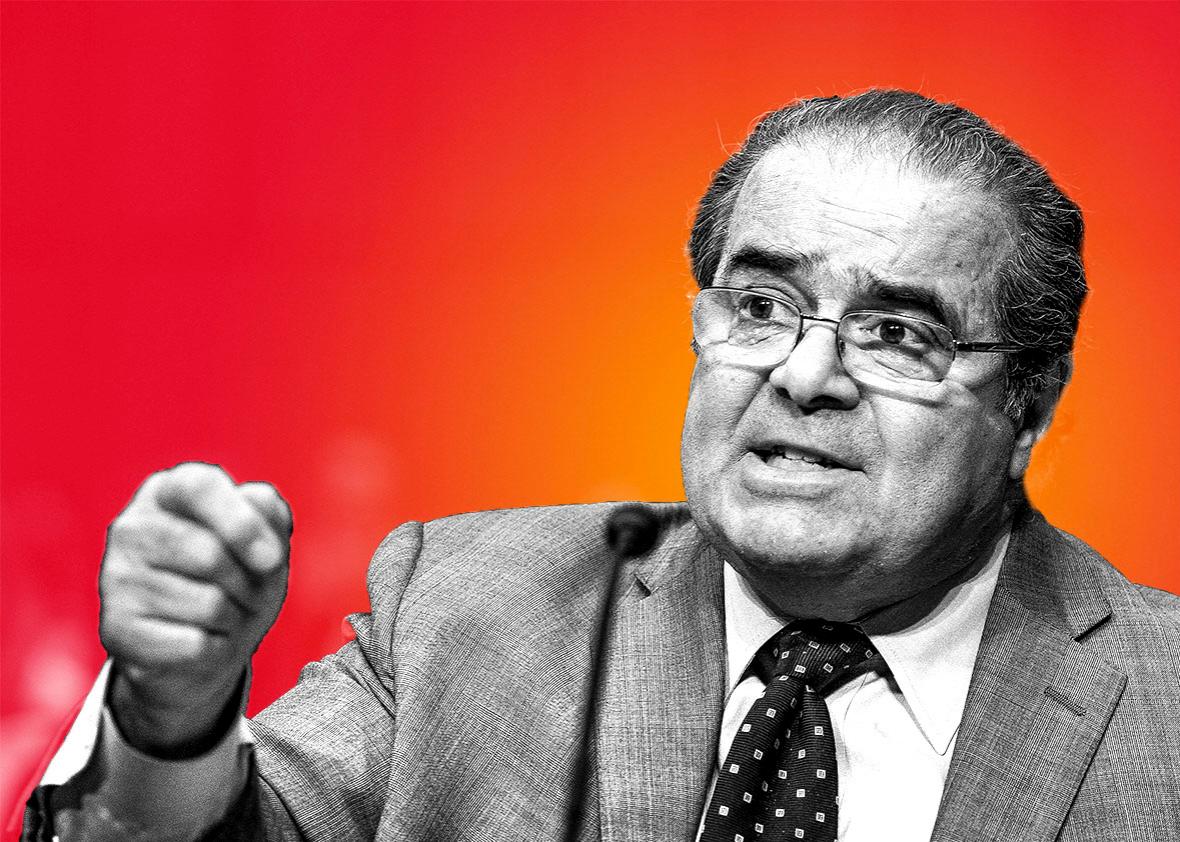

Appointed to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986, Justice Antonin Scalia was the pugilistic and charismatic face of the court’s conservative wing. He died Saturday at the age of 79, leaving one of the most important intellectual legacies in Supreme Court history. With a staggeringly original mind, a ferociously quotable pen, and a cult following among young conservatives, Scalia made believing in the Framers cool again.

His almost 30-year tenure at the high court was transformational; perhaps most striking was his advocacy for originalism (or, more correctly, textualism)—a mode of constitutional interpretation that focused on the interpretation of the law by looking scrupulously to the intent of the legislators who wrote the law. Under his leadership, the court went from an institution often divided on the best way of interpreting the Constitution to a court that often deferred completely to Scalia’s textualist preferences. So profound was his originalist influence on his colleagues that when the court decided United States v. Heller in 2008, even the liberal dissenters approached the D.C. gun laws through the lens of originalism, leading many commentators to observe that Scalia had won: “We are all originalists now.”

There is no doubt that Scalia was a hard-line conservative—a juggernaut in reversing the Warren court revolution—he led the court into culture war battles over race, abortion, religion, the death penalty, and gay rights. But Scalia was also an occasionally surprising hard-liner when it came to protecting the rights of criminal defendants who could not, for instance, challenge witnesses testifying against them or the privacy rights of those who objected to the use of thermal imaging in searches of their homes.

Professionally, Scalia was perhaps most famous for his deep friendship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg—one of the court’s staunchest liberals. His regard for her intellect was so profound that it transcended all ideology. While he was the court’s larger-than-life bon vivant, and she was its diminutive whisperer, the two could not have been more respectful of each other. In an article I once did about Ginsburg’s approach to persuasion, Scalia noted, “She does it quietly; but she’s very effective.”

Scalia did nothing quietly. His speeches were bombastic, his dissents lashed and slashed: In his famous dissent on the King v. Burwell ruling that upheld the Affordable Care Act, Scalia accused his colleagues of committing “interpretive jiggery-pokery” and dismissed their reasoning as “pure applesauce.” Dissenting in a case about the Defense of Marriage Act, he sneered that the majority was using “legalistic argle-bargle.” Sometimes the caustic tones would nudge other justices away from Scalia’s camp. But it won him undying admiration among the legion of young law students and lawyers who found his prose eminently readable, urgent, and scorching. On a court largely embodied by reserve and dignity, Scalia lived and wrote in Technicolor.

In the coming days we will all shout and holler and smoke and drink and swear as we try to figure out what having an eight-member court will mean in what would have been the most important term in decades—with affirmative action, abortion, immigration, union rights, and contraceptive rights teed up on the docket. Scalia would likely have wanted nothing less.