Carl Staples moved his family to Shreveport, Louisiana a few years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Forty years later, Staples had to walk past a Confederate flag atop a monument to the Confederacy on the Shreveport courthouse lawn in order to report for jury duty. When the lawyers asked Mr. Staples whether he could be an impartial juror in a death penalty case—a question routinely asked and answered in the affirmative in courthouses across the country—his response likely stunned the room:

The Confederate flag flies here. This is a symbol of one of the most, to me, one of the most heinous crimes ever committed to another member of the human race, and I just don’t see how you could say you’re here for justice and then again you continue to overlook this great injustice by continuing to fly this flag which continues to put salt in the wounds of people of color. I don’t buy it. I don’t buy it.

In 2011, I travelled to Louisiana and stood with Carl Staples on the courthouse lawn. We asked Shreveport to take down that flag. During my visit, I learned that Caddo Parish, which includes Shreveport and has a population of about 250,000 people, has been the site of more lynchings of black men than all but one other county in America. In the 1920s, even progressives justified the use of capital punishment on the grounds that whites would demand more lynchings of blacks if the death penalty wasn’t available. No white person has ever been executed for killing a black man in Caddo—or anywhere in Louisiana for that matter.

Carl Staples’ quiet and courageous assertion sent forth a ripple that became a wave. In November of 2011, the County Commissioners voted to take down the Confederate Flag. Unfortunately, that symbolic gesture has not yet improved the administration of justice in the county. But that could change. While Caddo Parish remains one of the only counties in the United States that continues to repeatedly impose new death sentences, this dubious distinction is now coming under increasing public scrutiny. The result is that, even in this locale, the death penalty is collapsing under the weight of its own corruption and cruelty.

In 2014, Glenn Ford, a Caddo Parish resident, was exonerated after spending 30 years in solitary confinement on death row for a crime he did not commit. He died from untreated cancer shortly after his release from Angola State Penitentiary. Marty Stroud, the prosecutor who put Ford on death row, wrote a public apology:

I now realize, all too painfully, that as a young 33-year-old prosecutor, I was not capable of making a decision that could have led to the killing of another human being. No one should be given the ability to impose a sentence of death in any criminal proceeding. We are simply incapable of devising a system that can fairly and impartially impose a sentence of death because we are all fallible human beings.

In response to Stroud’s act of humility, Dale Cox, then acting district attorney of Caddo Parish and a prosecutor who was single-handedly responsible for one-third of Louisiana’s death sentences since 2010, told a local reporter “we need to kill more people.” Cox called society “a jungle” and expressed support for the death penalty as “revenge.”

Cox’s comments have drawn outrage not just within Caddo, but throughout the nation. He announced that he would not run for re-election as district attorney because his views on the death penalty were so out of step with his community.

In November, the voters of Caddo Parish elected Judge James Stewart to be the first black district attorney of Caddo Parish. He ran on a reform platform. Days later, Dale Cox resigned from the office.

Like the monument commemorating the Confederacy, Caddo Parish is a symbol, in this case a symbol of the death penalty’s last stand in America. It offers a vivid example of the personality-driven process that is virtually all that is left of the death penalty today. Caddo did not become the poster child for a wildly dysfunctional capital punishment system because its inhabitants were more bloodthirsty than those living in other counties across the Deep South. It became an outlier because of prosecutors like Dale Cox, who were overzealous and reckless in their single-minded pursuit of death sentences.

In addition to facing the overzealous prosecutors, 75 percent of those sentenced to death since 2005 were represented by a defense lawyer who is no longer certified to try capital cases under new statewide standards. One such lawyer, Daryl Gold, once offered less than a day’s worth of mitigation for a client accused of murdering his infant son. In a case that has now received national attention, this man was convicted and sentenced to death despite the fact that the state’s own medical examiner couldn’t be certain that the death was a homicide.

Combine these factors with a legacy of racial terror and continuing institutional racism—for example, a recent study that found that black candidates were struck from juries three times as often as whites in Caddo—and you have the recipe for a dysfunctional death penalty system. A broken system preys upon the most fragile and least competent among us. It can hardly be surprising then, that in this Parish juries sentenced an individual like Corey Williams to death. (Williams, who was likely framed for murder, had his sentence commuted to life in prison because he was 16 at the time of his crime and intellectually disabled. Both are factors that constitutionally exclude him from the death penalty.)

Similarly, Laderick Campbell, an 18-year-old ninth-grade dropout and former special education student with a 67 IQ and a severe mental illness, was also sentenced to death. The trial judge wondered aloud whether Campbell was “delusional” during jury selection in the case.

I represented Brandy Holmes, who was named after her mother’s favorite drink while pregnant, and who attempted suicide as a child after she was raped. Caddo prosecutors sought the death penalty despite the fact that Brandy suffers from fetal alcohol syndrome, organic brain damage, post-traumatic stress disorder, and major depression.

Caddo offers us a microcosm of what remains of the death penalty in America today. In practice, capital punishment is increasingly being rejected by prosecutors, juries, judges, legislatures, and the public across the country. Only 10 counties out of 3,142 produced more than six death sentences between 2010 and 2015.

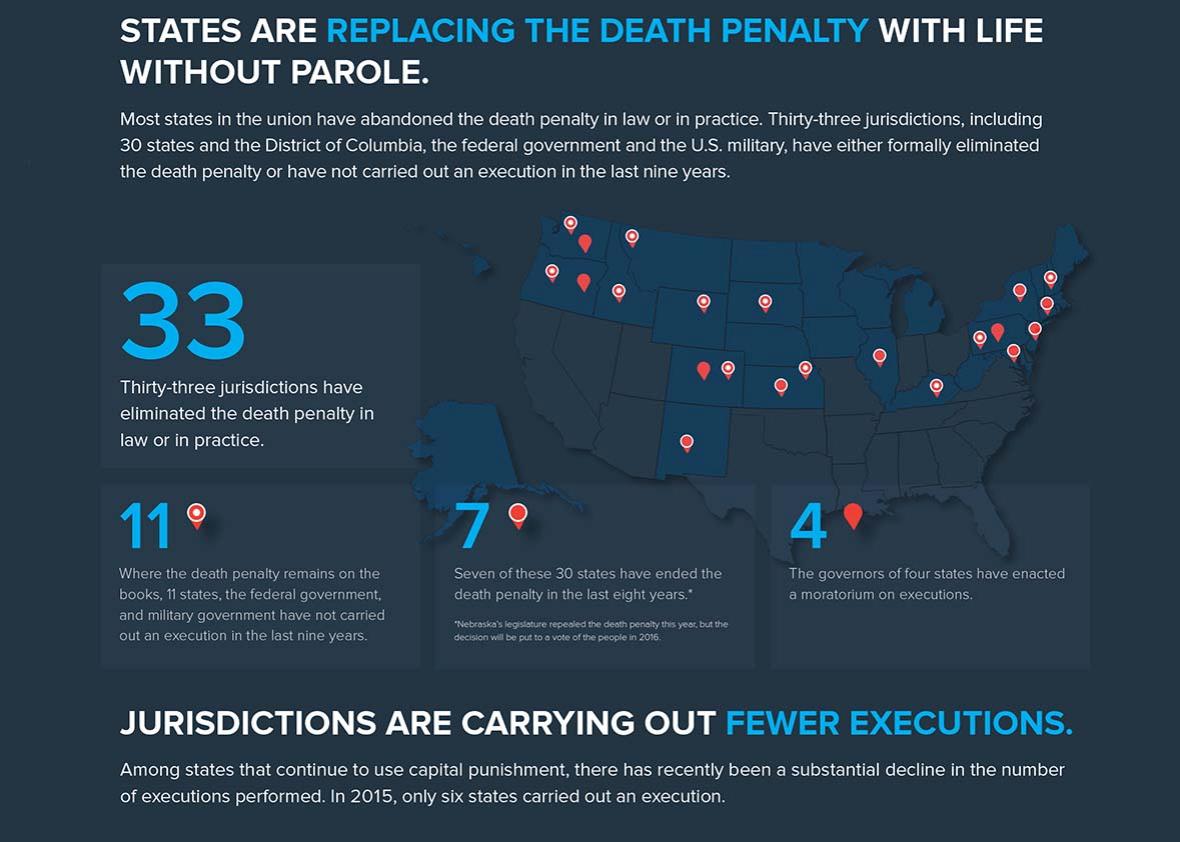

There is strong and growing national consensus that the death penalty should be replaced with life without parole. Thirty-three jurisdictions, including 30 states and the District of Columbia, the federal government, and the U.S. Military, have formally abandoned the death penalty or have not carried out an execution in more than nine years. The governors of Oregon, Washington, Pennsylvania, and Colorado have vowed not to perform an execution. Seven states have replaced the death penalty with life without parole in the past decade, and more than a dozen other legislatures have considered repealing in recent years. Several may achieve that goal within the next few years.

Chart courtesy of Harvard Law School

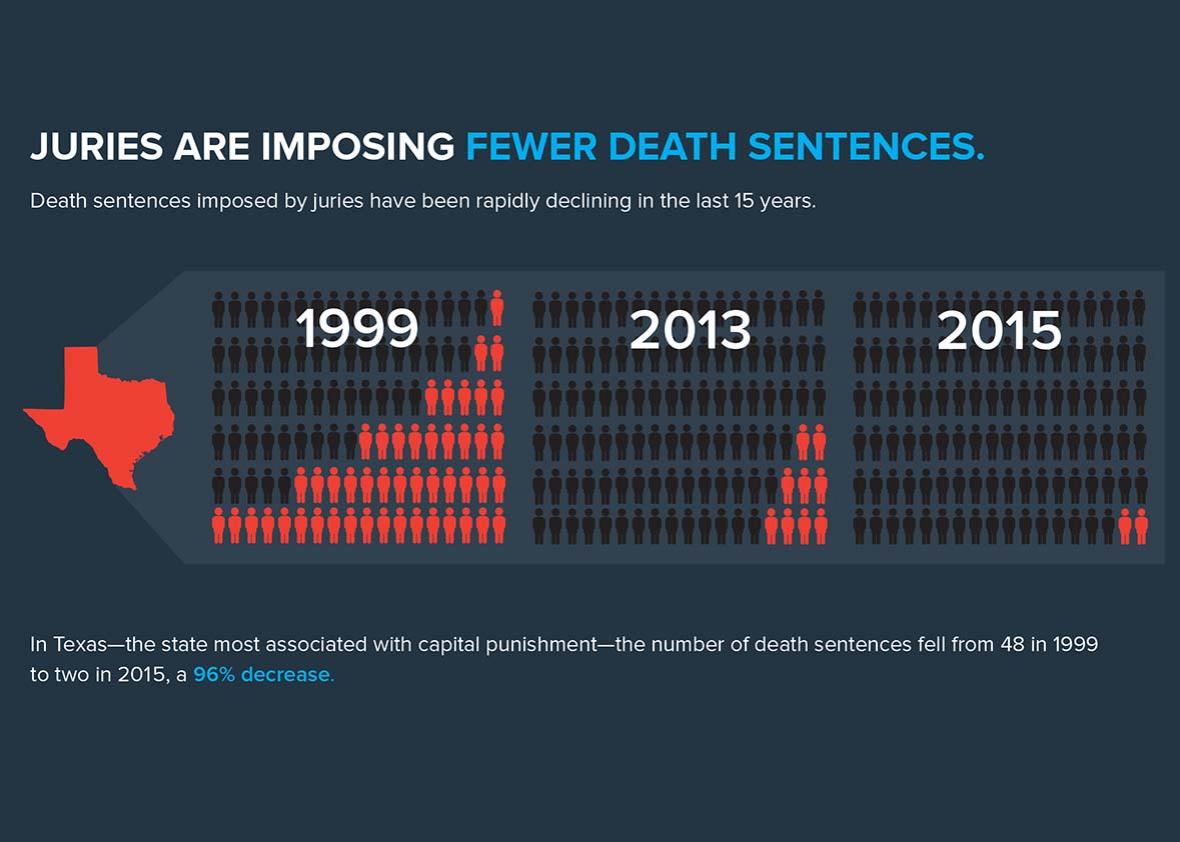

In 2015, juries returned the fewest new death sentences—49—in modern history.

Fourteen of those sentences came from split juries in Alabama and Florida. These are two of only three states that allow non-unanimous jury verdicts in capital cases.

Nineteen of those sentences came from states—namely, California, Kansas, Nevada and Pennsylvania—where no one has been executed in at least nine years, and in the case of Kansas, in more than 50 years.

And, in a remarkable turnabout, Texas, a state that sentenced 48 people to death in 1999—only one sentence fewer than the national total this year—had just two confirmed death sentences in 2015.

Chart courtesy of Harvard Law School

Six states performed a total 28 executions this year, the lowest number in 25 years. Three-quarters of the people executed in 2015 suffered from crippling intellectual or mental disabilities, endured extreme childhood trauma and abuse, or were executed despite doubts about their guilt.

Chart courtesy of Harvard Law School

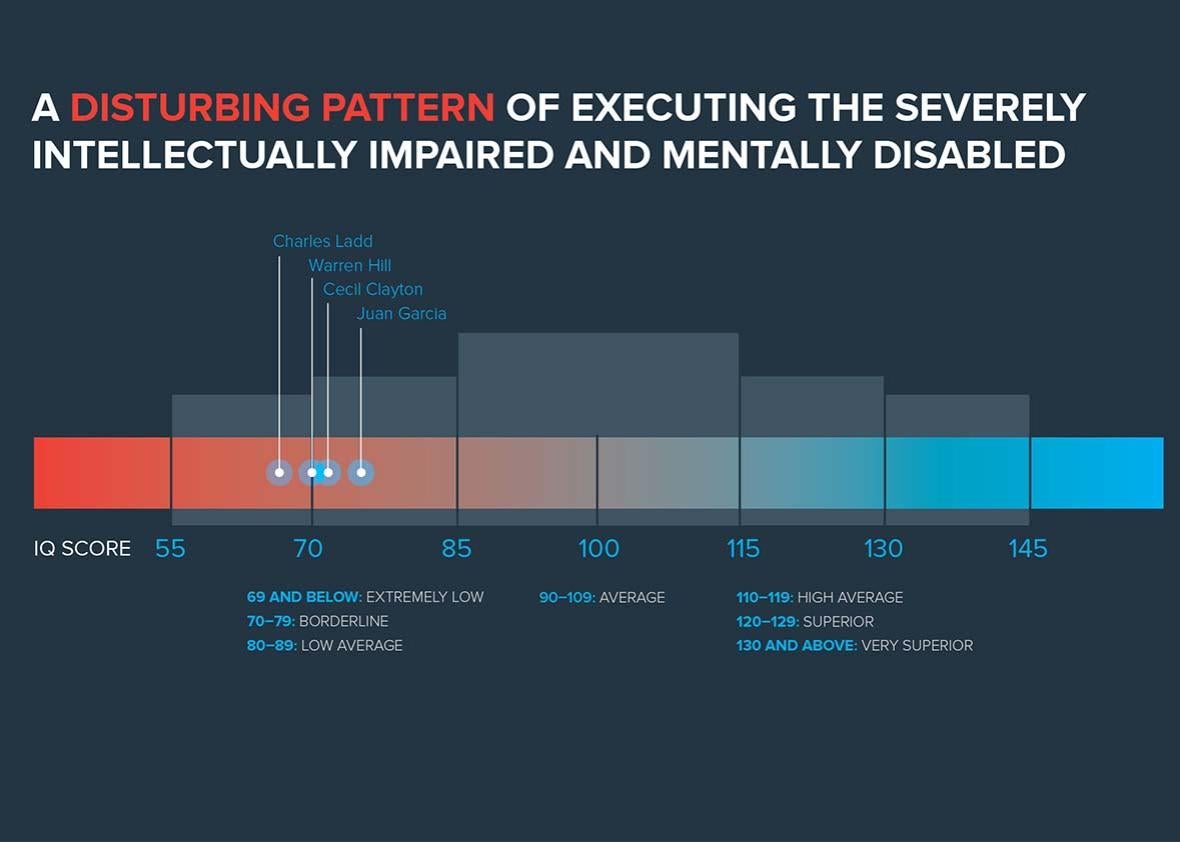

Seven of the executed individuals had an intellectual impairment or brain injury. Cecil Clayton had a 71 IQ score and lost 20 percent of his prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for decision-making—in a sawmill accident. Three doctors declared Clayton incompetent to be executed.

Texas executed Robert Charles Ladd, who had a 67 IQ score. A state-employed psychiatrist said Ladd was “rather obviously retarded.” Texas also executed Juan Garcia, who had an IQ score of 75, which puts him in the lowest 5 percent of the population. Garcia was just 18 years old when he was sentenced to die. If he had committed the same crime six months earlier, he would have been ineligible for the death penalty.

Georgia executed Warren Hill, a man with a 70 IQ score, even though three state-employed physicians found that he was intellectually disabled.

Chart courtesy of Harvard Law School

Seven executed individuals suffered from serious mental illnesses. Georgia executed Andrew Brannan, a decorated Vietnam combat veteran, diagnosed with both post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder. The Department of Veteran Affairs categorized him as 100 percent disabled.

Texas executed Raphael Holiday, who was diagnosed with depression with psychotic features. A physician testified that his mental health background suggested psychotic decompensation, which meant that he had “some loss of contact with reality.” Texas also executed Kent Sprouse, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by a court-appointed psychiatrist who said he was “psychotic, paranoid, believed people were persecuting him, and did not understand the wrongfulness of his conduct.”

The crippling impairments of many of the people executed this year reveal the excessiveness of the death penalty as a punishment. As someone who knows the pain of losing a loved one to homicide, I can understand the desire to hold people who commit heinous crimes accountable. I lost my beloved sister, Barbara Jean Ogletree Scoggins, who served as a police officer with the Merced County Sheriff’s Office, to murder in the 1980s. However, extracting the ultimate revenge from persons who have severe mental disabilities, borderline intellectual functioning, or impairments as the result of serious childhood abuse and trauma crosses a moral line when we have other options, such as life without parole, available to us.

The death penalty in America today is the death penalty of Caddo Parish—a cruel relic of a bygone and more barbarous era. We don’t need it, and I welcome its demise.