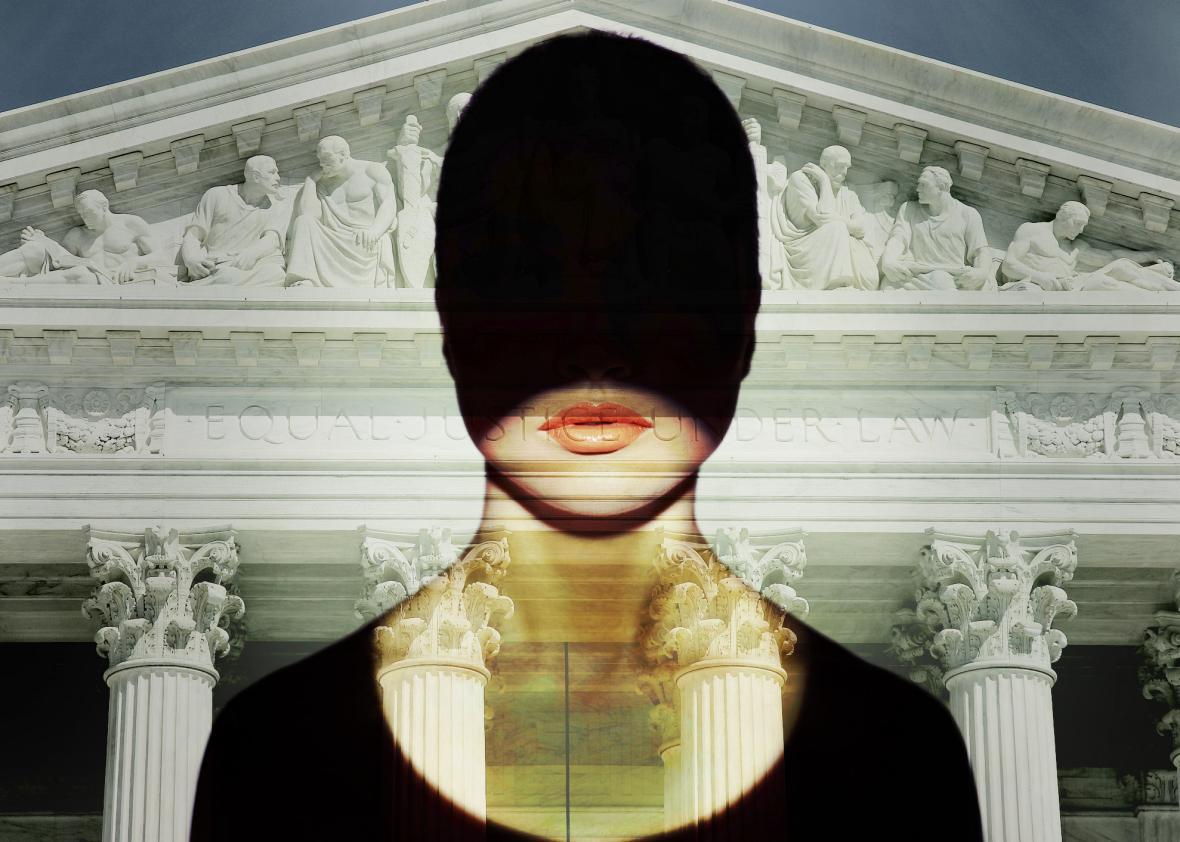

Lots of women get abortions—about 1 million each year in the United States alone—but few are eager to talk about their experiences. Unlike same-sex marriage, a constitutionally related right whose appeal derived largely from real-world stories, abortion is typically defended as an abstract, theoretical decision. That gives antiabortion advocates a distinct advantage: They can point to the small group of women who now regret their abortions while abortion rights groups struggle to put a compelling human face on the importance of abortion access.

The extent of this problem became apparent in the 2007 Supreme Court decision Gonzales v. Carhart. In his majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that “it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained. Severe depression and loss of esteem can follow.” (Kennedy admitted that “we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon”—which makes sense, since all available data strongly suggest that extremely few women actually regret their abortions and that the predominant emotion following abortion is relief.) The line was doubly troubling coming from the court’s swing vote on abortion rights. Kennedy once joined an opinion declaring that the “ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.” Had he now decided that millions of faceless, nameless women would be better off emotionally if the state forced them to carry each pregnancy to term?

In March, the court will hear its first major abortion case in nearly a decade, Whole Women’s Health v. Cole, a challenge to Texas’ stringent laws designed to shutter most abortion clinics in the state. Once again, Kennedy will determine the outcome of the case. Once again, dozens of advocacy groups and law firms are scrambling to explain why abortion is a fundamental liberty that helps real women secure their constitutionally protected right to equal dignity.

The avalanche of amicus briefs is impressive—but one brief towers above the rest. Aided by the Center for Reproductive Rights, the powerhouse firm Paul, Weiss put together an astonishing document, signed by 113 female attorneys, detailing the importance of abortion rights in their own lives. “To the world, I am an attorney who had an abortion, and, to myself, I am an attorney because I had an abortion,” the brief begins. What follows is a series of gripping narratives about how abortion access helped women escape from poverty and abuse and rise to the heights of the legal profession.

On Thursday, I spoke with Allan Arffa and Alexia Korberg, who spearheaded the brief, about their bid to put a human face on a procedure that many—including, it seems, Justice Kennedy—find lamentable. Our discussion has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Stern: How did the idea for the brief originate?

Korberg: The Center for Reproductive Rights reached out to Allan to see if he would take the lead in putting together a brief on behalf of female attorneys. From there, it evolved organically—more so than any brief I’ve ever been a party of. As signers came forward and began to relate their experiences, it became evident to us how powerful their stories were, and that the brief should be about their experiences. The themes that emerged were remarkably similar, especially access to educational opportunities and escaping abuse. And the overarching theme was clear: Were it not for their safe and legal access to abortion, these women wouldn’t have had the lives they did.

The stories in the brief are clearly powerful. But how are these personal narratives helpful in explaining why abortion should be protected as a fundamental right?

Arffa: We try to tie it to the language in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which framed abortion rights as a way to protect a woman’s right to participate fully in the economic and social life of the country. These stories very much support that notion. We were trying to make the idea more visible, more concrete. We wanted to show how these experiences verified that foundation for Casey—how these women would not have been able to participate as fully, or at all, in the economic and social life of the country, had it not been for their constitutionally protected right.

Korberg: The Casey court said that a necessary part of the legal analysis wasn’t just the right itself, but the reliance upon that right over decades, and the generation of women who have come of age in a country in which they did have the legal right to an abortion. We wanted to show the consequences of that reliance: that the nation is so much better, stronger, and richer because more women are in the workforce and politics and the arts. The law is a finer profession because women are a part of it. It was profound hearing again and again from these women that they would not have been able to practice law had they been denied access to abortion.

Many legal analysts think the sweeping language in the same-sex marriage decision Obergefell v. Hodges speaks indirectly to the constitutional importance of abortion. Do you believe that decision helps your argument?

Korberg: We saw there that the court was profoundly interested in hearing about the real-world impact on real people of the issues at stake. Justice Kennedy was very taken with the briefs featuring narratives on behalf of the children of same-sex couples. That gives us some optimism that the court is interested and willing to hear from people like our clients talking about how important a role their abortions played in their lives.

The sweep of your brief is remarkable—113 women ultimately signed on. Has this been in the works for a while?

Korberg: Outreach took place over two and a half weeks—but chiefly between Christmas and New Year’s. That was the entire runway. It was such a short window. We’ve gotten even more interest since then. If there had been more time, there are many more women who would have signed and told their stories.

Arffa: I won’t go into what it did to our vacations. When the court told us the brief was due Jan. 4, I said, “What?!” This was in mid-December.

You put a great deal of faith in the signers’ ability to persuade the justices through their own narratives.

Korberg: We got out of the way and let our clients tell their stories. The first real client I ever had was Edie Windsor. I learned early on to shut up and listen to your client.