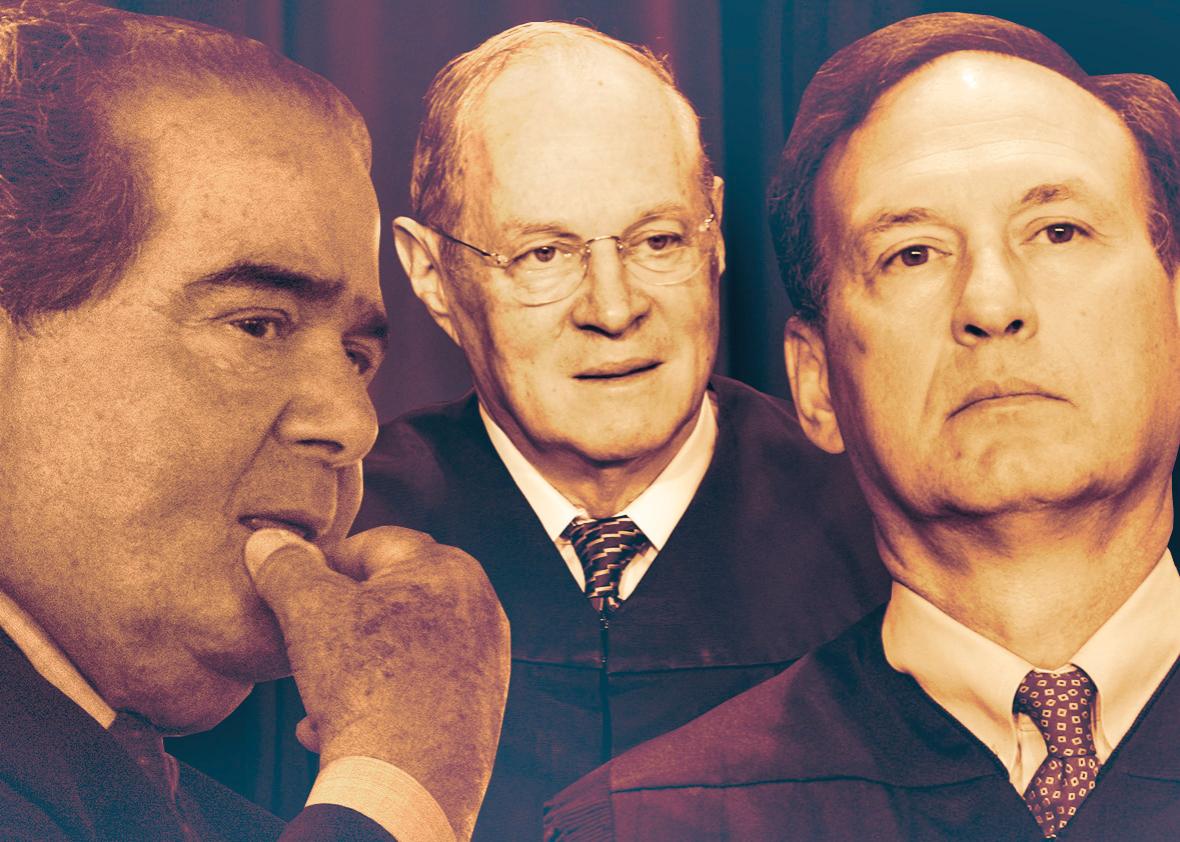

As a deeply divided U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the latest challenge to affirmative action policies in higher education last week, the swing vote on the court—Justice Anthony Kennedy—was fairly quiet. But lines of questioning advanced by two of his colleagues—Justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito—may well help tip Kennedy in one direction or the other.

Scalia and Alito are often thought of as twins on the Supreme Court—both are Italian-American conservatives, with similar names. In fact, when Alito was nominated, some people derisively referred to him as “Scalito.” But the two justices’ tactical approaches to the oral arguments in Fisher v. University of Texas II last Wednesday could not have been more different. Both justices clearly oppose the University of Texas at Austin’s policy that allows for some use of race in admissions. But at argument, Scalia denigrated the abilities of black students, which is likely to backfire with Kennedy, while Alito championed the ability of working-class black and Latino students to do well and become leaders in society—an approach far more likely to positively influence the swing justice.

Scalia’s widely reported line of questioning Texas’ lawyer, Greg Garre, which spurred a major backlash, suggested that minority students, given preference by universities, often end up struggling academically. There is a legitimate academic debate over what’s known in the literature as “mismatch”: At what point do the size of preferences (for athletes, legacies, low-income students or minority pupils) become so large that they end up putting beneficiaries in over their heads? But Scalia butchered the issue by speaking in broad strokes about the competency of black students. Using highly inflammatory language, he asked Garre whether black students might be helped by “having them go to a less advanced school … a slower-track school where they do well.” Maybe UT Austin ought to have “fewer” black students, he mused, because “when you take more, the number of blacks, really competent blacks admitted to lesser schools, turns out to be less.”

Alito, whose questioning has received far less media attention, took a diametrically opposed stance from Scalia. Alito showed great confidence in the abilities of minority students. Moreover, he implied that UT Austin and the Obama administration were classist in denigrating the ability of poor and working-class minority students to be leaders in American society.

Alito came out as a champion of Texas’s top-10-percent plan, which admits students in the top of every high school class in Texas, irrespective of SAT or ACT scores. The plan was adopted in the 1990s after a lower court banned the use of race at UT Austin in Hopwood v. Texas. Because Texas high schools are highly segregated by race, the plan ends up benefitting many working-class black and Hispanic students in racially isolated schools. As it turns out, the plan—coupled with a program giving an admissions boost to economically disadvantaged students of all races—eventually produced slightly more black and Latino representation than had been achieved with racial preferences prior to Hopwood.

But when the U.S. Supreme Court approved racial preferences at the University of Michigan Law School in 2003, UT reinserted race into admissions. Today, three-quarters of the class is admitted through the top-10-percent plan and one-quarter through holistic admissions that consider many factors, including race. Abigail Fisher, a white student, sued in 2008 when she was denied admissions to UT Austin, saying race should not be a factor.

UT responded, in part, that race was necessary to admit upper-middle-class black and minority students from integrated high schools who tended not to be admitted through the top-10-percent plan. These students could serve as bridge builders and leaders, UT and the Obama administration argued. At argument, Alito pounced on this line of reasoning. When the solicitor general argued that the 10-percent plan was insufficient because the U.S. military needs diverse leaders, Alito asked: “But do you think that the African-American and Hispanic students who were admitted under the top-10-percent plan make inferior officers when compared to those who were admitted under holistic review?”

It was a brilliant question that turned the tables. If Scalia made statements that were seen by some as borderline racist, Alito put UT and the Obama administrative on the defensive for seeming to make classist assumptions about the working-class black and Latino students admitted to UT under a race-neutral policy.

Alito also pointed out that the minority strivers admitted through the top-10-percent plan do well academically. In 2000, when the 10-percent plan was in effect but racial preferences were not, UT’s president noted that “minority students earned higher grade point averages last year than in 1996 and have higher retention rates.” Moreover, careful research by Sunny Niu and Marta Tienda of Princeton University found that black and Hispanic students admitted through the percentage plan “consistently perform as well or better” than white students ranked at or below the third decile.

Furthermore, by stressing the virtues of the top-10-percent plan, Alito went directly to Kennedy’s key concern about affirmative action, as expressed in prior cases. Like the American public, Kennedy has been torn: He values diversity and recognizes that race still matters in American society, but he doesn’t like the idea of explicitly counting skin color in deciding who gets ahead. Programs like the top-10-percent plan and socioeconomic affirmative action disproportionately benefit black and Latino students and are precisely the types of programs Kennedy seemed to be pushing universities toward when he required, in Fisher I, that universities bear “the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”

In the oral argument, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg faulted the 10-percent plan for relying on racial segregation, but she has it exactly backwards. As Georgetown law professor Sheryll Cashin notes, place-based approaches help “those who are actually disadvantaged by structural barriers” rather than enabling “high-income blacks to claim the legacy of American apartheid.” As I document in a new report, Achieving Better Diversity, these new alternatives to racial preferences, if properly structured, can achieve a robust socioeconomic and racial diversity that improves upon current race-based programs, which are generally limited middle- and upper-class minority students.

After last week’s oral arguments in Fisher II, it’s not certain where Kennedy is headed. It is possible that backlash against Scalia’s rant will push Kennedy to decide that now is not the time to pull the plug on racial preferences. But if Kennedy listens instead to the strong arguments advanced by Alito, he may help usher in new forms of affirmative action across the country that are fairer and recognize that bright working-class students of all races have a great deal to offer our nation.