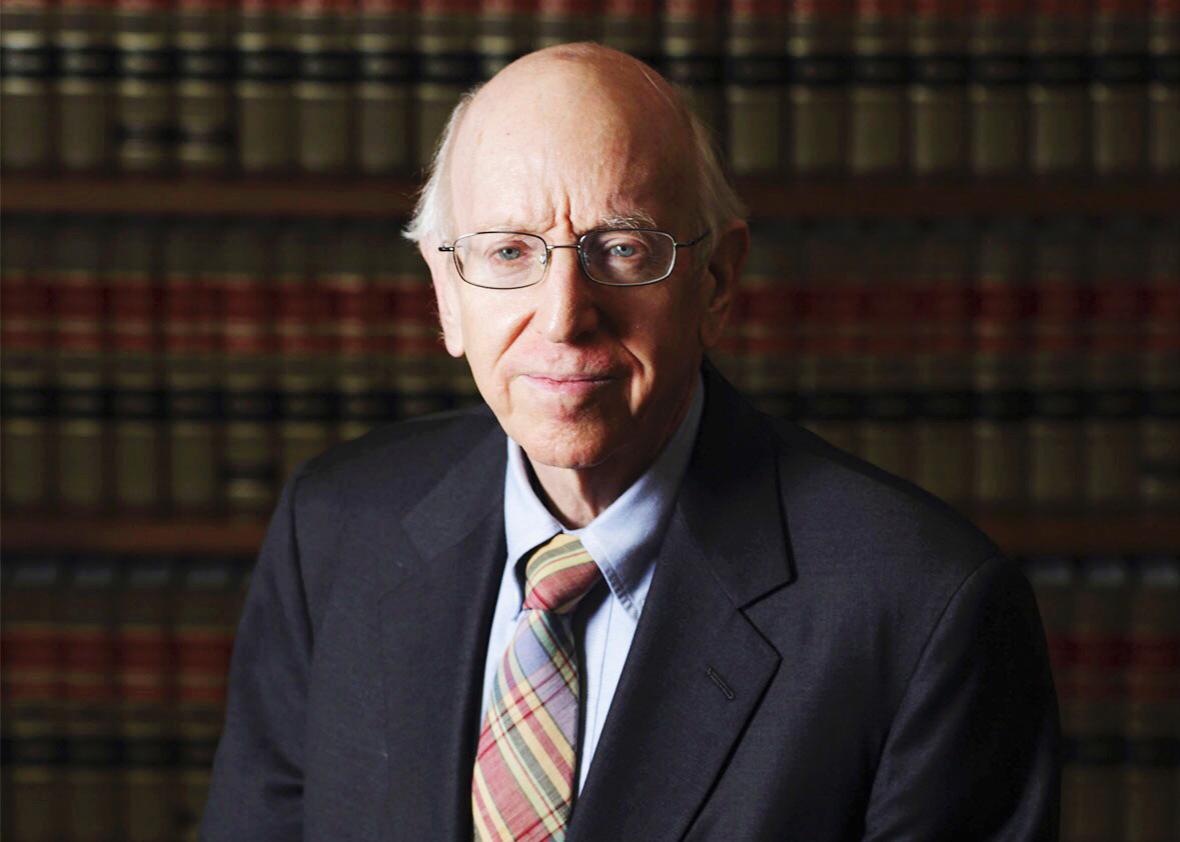

Judge Richard Posner, writing for a divided 2–1 panel of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, ruled in an opinion filed on Monday that Wisconsin’s 2013 law requiring all abortion providers to obtain admitting privileges at nearby hospitals is unconstitutional. Admitting privileges are one of the two issues the Supreme Court agreed a little more than a week ago to decide when it accepted a challenge to Texas’ omnibus abortion statute HB 2.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, Wisconsin is one of 14 states that have required similar admitting privileges. Such provisions have been declared unconstitutional in six of those states. Posner, appointed to the 7th Circuit by Ronald Reagan, and long considered one of the most important conservative legal thinkers in the country, had already voted in this same case, in 2013, to keep an emergency injunction in place, finding the medical evidence for the admitting privileges requirement “lacking.” Posner has also criticized the Supreme Court in Slate for striking down a Massachusetts law that kept abortion protesters away from abortion seekers attempting to enter clinics.

The Wisconsin law was passed on Friday, July 5, 2013 and required compliance by the following Monday, July 8—in effect, affording doctors performing abortions one weekend to obtain admitting privileges at hospitals within a 30-mile radius. Planned Parenthood and Affiliated Medical Services filed suit, claiming that the new rule would force Affiliated’s clinic in Milwaukee to shut down altogether because doctors couldn’t get admitting privileges and that the burden on the remaining clinics would be extreme. An injunction kept the law from going into effect, and this past March, after a trial, U.S. District Judge William Conley found the law unconstitutional, writing that the law served no legitimate health interest. The state appealed, arguing that the statute protects the health of women who experience complications from an abortion. This case was argued at the court of appeals in October. Judge Daniel Manion was the lone dissenter, finding that the law genuinely protects women’s health and doesn’t amount to an undue constitutional burden.

As Posner, writing for himself and Judge David Hamilton, points out in this week’s opinion, the two-day limit on getting privileges was telling: “There was no way an abortion doctor, or any other type of doctor for that matter, could obtain admitting privileges so quickly, and there wouldn’t have been a way even if the two days hadn’t been weekend days. As the district court found, it takes a minimum of one to three months to obtain admitting privileges and often much longer.” Posner goes on to note that the practical effects on the state’s four clinics would have been devastating: Two of the state’s four abortion clinics would have shut down, and the third would have halved its capacity.

Posner then contends that the onerous two-day deadline to obtain admitting privileges suggests the state’s true motive, which “is difficult to explain save as a method of preventing abortions that women have a constitutional right to obtain. The state tells us that ‘there is no evidence the [Wisconsin] Legislature knew AMS physicians would be unable to comply with the Act.’ That insults the legislators’ intelligence. How could they have thought that an abortion doctor, or any doctor for that matter, could obtain admitting privileges in so short a time as allowed?”

Posner then turns to the state’s foundational claim that the admitting privileges requirement is a genuine attempt by the state to protect the mother’s health: “A woman who experiences complications from an abortion will go to the nearest hospital, which will treat her regardless of whether her abortion doctor has admitting privileges. As pointed out in a brief filed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Medical Association, and the Wisconsin Medical Society, ‘it is accepted medical practice for hospital-based physicians to take over the care of a patient and whether the abortion provider has admitting privileges has no impact on the course of the patient’s treatment.’ ”

He also points out that contrary to the state claims that there is something inherently dangerous about abortion itself, “complications from an abortion are both rare and rarely dangerous—a fact that further attenuates the need for abortion doctors to have admitting privileges.” Reviewing the scientific literature in the record, Posner notes that “studies have found that the rate of complications is below 1 percent; in the case of complications requiring hospital admissions it is one-twentieth of 1 percent.” He points out that the kinds of horror stories used to justify these admitting privileges laws are so rare as to be almost nonexistent.

Posner tartly observes that: “No other procedure performed outside a hospital, even one as invasive as a surgical abortion, is required by Wisconsin law to be performed by doctors who have admitting privileges at hospitals within a specified radius of where the procedure is performed. And that is the case even for procedures performed when the patient is under general anesthesia, and even though more than a quarter of all surgical operations in the United States are now performed outside of hospitals.” He notes that “Wisconsin appears to be indifferent to complications of any other outpatient procedures, even when they are far more likely to produce complications than abortions are. For example, the rate of complications resulting in hospitalization from colonoscopies done for screening purposes is four times the rate of complications requiring hospitalization from first-trimester abortions.”

Posner then writes that the law simply does not permit this sort of feigned concern for a woman’s health to trump her right to terminate a pregnancy: “Until and unless Roe v. Wade is overruled by the Supreme Court, a statute likely to restrict access to abortion with no offsetting medical benefit cannot be held to be within the enacting state’s constitutional authority.”

Posner makes short work of the state’s argument that even if clinics close in Wisconsin, patients can always just travel the 90 miles from Milwaukee to Chicago for the procedure. The judge shows a deep and important understanding of who the prospective clients would actually be:

It’s also true … that a 90-mile trip is no big deal for persons who own a car or can afford an Amtrak or Greyhound ticket. But more than 50 percent of Wisconsin women seeking abortions have incomes below the federal poverty line and many of them live in Milwaukee (and some north or west of that city and so even farther away from Chicago). For them a round trip to Chicago, and finding a place to stay overnight in Chicago should they not feel up to an immediate return to Wisconsin after the abortion, may be prohibitively expensive. The State of Wisconsin is not offering to pick up the tab, or any part of it. These women may also be unable to take the time required for the round trip away from their work or the care of their children. The evidence at trial, credited by the district judge, was that 18 to 24 percent of women who would need to travel to Chicago or the surrounding area for an abortion would be unable to make the trip.

Then Posner applies the “undue burden” test from Planned Parenthood v. Casey to the facts above: “If a burden significantly exceeds what is necessary to advance the state’s interests, it is ‘undue’ which is to say unconstitutional. The feebler the medical grounds (in this case, they are nonexistent), the likelier is the burden on the right to abortion to be disproportionate to the benefits and therefore excessive.”

Finally, because he can, Posner pretty much just pantses the judges on the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and others who argue that the real intent of this admitting privileges law is to protect women:

A great many Americans, including a number of judges, legislators, governors, and civil servants, are passionately opposed to abortion—as they are entitled to be. But persons who have a sophisticated understanding of the law and of the Supreme Court know that convincing the Court to overrule Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey is a steep uphill fight, and so some of them proceed indirectly, seeking to discourage abortions by making it more difficult for women to obtain them. They may do this in the name of protecting the health of women who have abortions, yet as in this case the specific measures they support may do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion. This is true of the Texas requirement, upheld by the Fifth Circuit in the Whole Woman’s case now before the Supreme Court, that abortion clinics meet the standards for ambulatory surgical centers—a requirement that if upheld will permit only 8 of Texas’s abortion clinics to remain open, out of more than 40 that existed when the law was passed. And comparably in our case the requirement of admitting privileges cannot be taken seriously as a measure to improve women’s health because the transfer agreements that abortion clinics make with hospitals, plus the ability to summon an ambulance by a phone call, assure the access of such women to a nearby hospital in the event of a medical emergency.

The whole argument about admitting privileges is reduced above to three irreducible facts: The law will close significant numbers of clinics immediately; the law will not make women safer because existing systems already ensure they get care; clinic closures make many, many women less safe, as we have now seen in Texas where a new study estimates that 100,000 women have attempted to induce an abortion on their own. When state actors take the position that they are acting benevolently toward women, while they are in fact creating serious health risks, the courts have a responsibility to call out the sham reasoning for what it is. Or as Posner writes, in perhaps the most important line of an important opinion, “what makes no sense is to abridge the constitutional right to an abortion on the basis of spurious contentions regarding women’s health—and the abridgment challenged in this case would actually endanger women’s health.”