On Nov. 18, David Bowers, the mayor of Roanoke, Virginia, put a name, a face and a constitutional “you’ve got to be kidding” on the xenophobic madness currently gripping the nation. He started by calling for the suspension of all aid to Syrian refugees. Bowers went one further than those seeking just to stop aid or deny state resources, however; Bowers cited, with approval, the precedent of the United States interring 110,000 Japanese Americans following the bombing of Pearl Harbor: “I’m reminded that Franklin D. Roosevelt felt compelled to sequester Japanese foreign nationals after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and it appears that the threat of harm to America from ISIS now is just as real and serious as that from our enemies then.”

Bowers’ statement has been swiftly and roundly criticized by Virginia leaders, including Sen. Mark Warner, state Sen. John Edwards, and representatives of both the Republican and Democratic parties in the state, as well as those even closer to home in Roanoke, including his own vice mayor. Actor and activist George Takei invited Mayor Bowers to come see his Broadway show Allegiance, which tells the story of the four years Takei lived in an interment camp as a child, under the policy cited in the mayor’s public statement. Takei told him: “It is my life’s mission to never let such a thing happen again in America.”

Some might argue that Bowers is simply unaware that the mass internment of people of Japanese ancestry—including American citizens—is considered a blot on the nation’s constitutional history and one of the nadirs of civil liberties, in a history checkered with shameful moments. Yet Bowers, an attorney, has refused to take back his comments. Given a chance to clarify his position late Wednesday, Bowers called himself a student of Roosevelt: “I understand how difficult a decision he made, but in the light of what was going on at the time he made the right decision,” Bowers said.

Any student of FDR understands that the lesson of the Japanese internment camps is that fear makes us stupid and careless. Lives were ruined by intemperate and punitive racial policies that led to mass detention of those who bore the scantest racial connection to our enemies. At first blush we suspected that Bowers was simply learning his constitutional history from one of those Texas textbooks that rewrites epic moral failures as valorous events. But as bad as FDR’s internment order was, the enduring moral sin of the internment camps was that the Supreme Court had a chance to correct the mistake—and opted not to. That decision, as a technical matter, remains good law today.

Bowers is seemingly not alone in his conviction that the lesson of Korematsu v. United States—the Supreme Court’s massive failure to reverse and condemn FDR’s error—is that penning in those who look like your attackers is and was a tremendous idea that served the nation well. Luckily, Korematsu itself offers contemporaneous predictions, in the form of its eloquent dissenting opinions, that someday, history would be ashamed.

Following the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, by the Japanese, FDR issued Executive Order 9066, granting the U.S. military the power to designate military areas from which people could be excluded to protect domestic security. As part of implementing this order, the military went on to ban “all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien” from a designated coastal area stretching from Washington state to southern Arizona and set up internment camps to hold more than 100,000 people fitting this description—two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens—for the duration of the war.

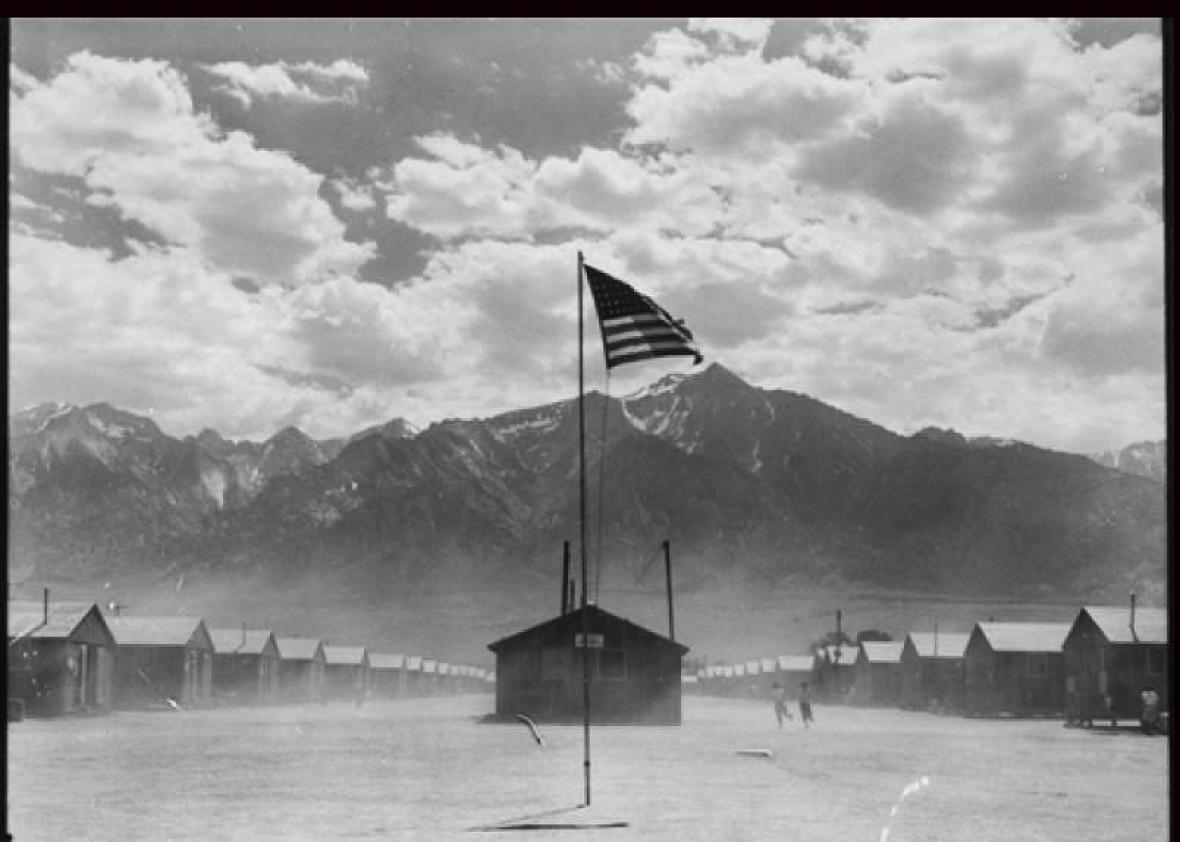

Dust storm at a War Relocation Authority center where evacuees of Japanese ancestry were held, July 3, 1942.

Photo courtesy National Archives

The case challenging this policy reached the Supreme Court in 1944. It involved Fred Korematsu, an American-born citizen of Japanese descent, who was convicted when he refused to leave his home in California in defiance of this order.

The U.S. military had asserted in this case that the loyalties of Japanese Americans could not be trusted to lie with the United States over Japan and that since separating “the disloyal from the loyal” was logistically impossible, the internment order had to apply to all Japanese Americans within the restricted area. The court agreed, finding that the nation’s security concerns trumped the Constitution’s protections, with a 6–3 majority upholding Korematsu’s conviction.

Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, explained that although “all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect” and subject to tests of “the most rigid scrutiny,” in some extraordinary circumstances, “pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions,” although “racial antagonism never can.”

Only through the long lens of history has the policy come to stand as a cautionary tale of what happens we betray core constitutional principles in times of fear and uncertainty. Today Korematsu is considered one of the court’s most cowardly opinions. A report issued by Congress in 1983 declared that the Supreme Court’s decision in Korematsu was “overruled in the court of history” and the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 contained a formal apology—as well as monetary reparations—to the Japanese Americans interned during the war. Justice Antonin Scalia has ranked Korematsu alongside Dred Scott, the 1857 decision denying citizenship to blacks, as among the court’s most shameful mistakes. In 1998, President Bill Clinton belatedly awarded Korematsu himself the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

But history also reminds us that the court itself did not speak with one voice when Korematsu came down. Even in the heat of the moment the three dissenting justices warned that the nation would someday regret the xenophobia and the recklessness the court itself had approved. Those dissents are a powerful reminder—even 70 years later—that sometimes our better angels know best.

In his Korematsu dissent, Justice Owen Roberts characterized the case as involving the conviction of a citizen “as a punishment for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition towards the United States.”

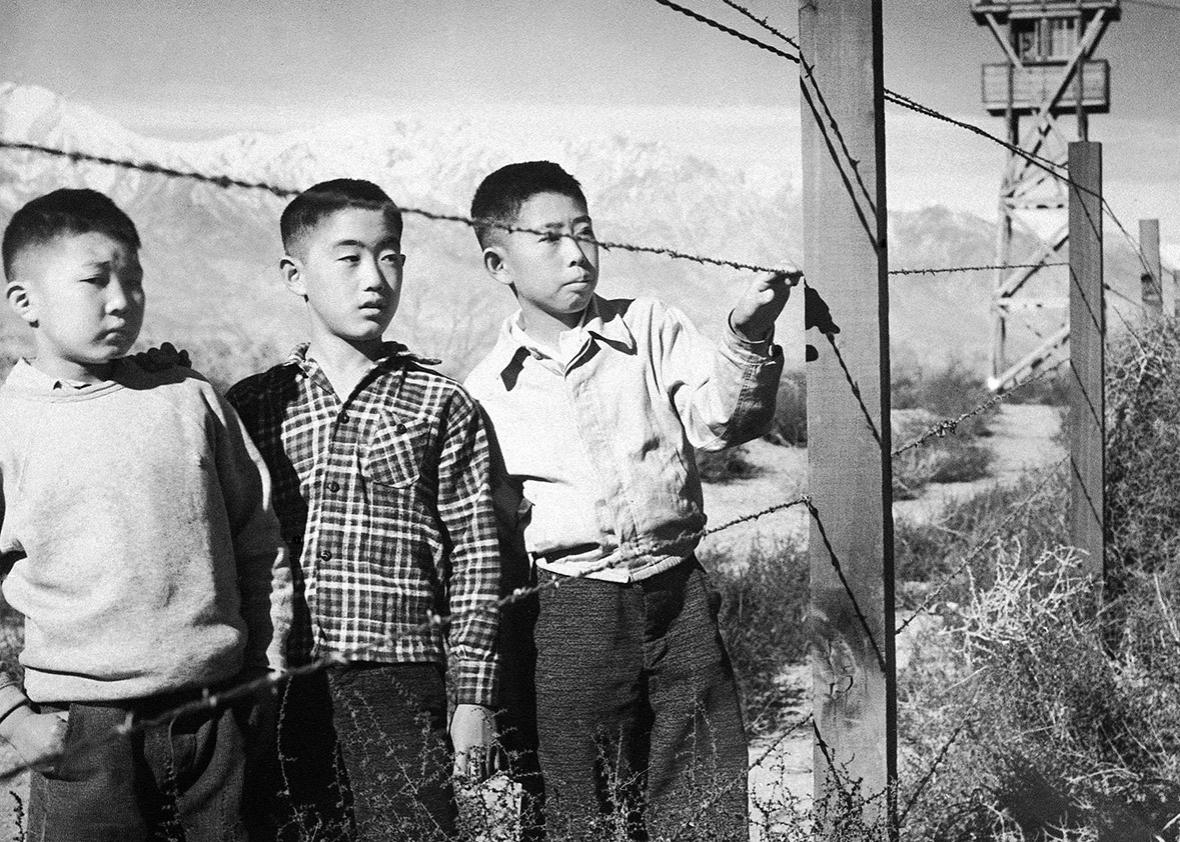

Photo by Dorothea Lange/Library of Congress

Justice Robert Jackson characterized Korematsu’s conviction as a result of “merely … being present in the state whereof he is a citizen, near the place where he was born, and where all his life he has lived.” The nation’s wartime security concerns, he contended, were not adequate to strip the internees of their constitutionally protected rights.

As Jackson noted, “if any fundamental assumption underlies our system, it is that guilt is personal and not inheritable. Even if all of one’s antecedents had been convicted of treason, the Constitution forbids its penalties to be visited upon him, for it provides that ‘no attainder of treason shall work corruption of blood, or forfeiture except during the life of the person attainted.’ But here is an attempt to make an otherwise innocent act a crime merely because this prisoner is the son of parents as to whom he had no choice, and belongs to a race from which there is no way to resign.”

Jackson’s opinion goes on to caution what it means when a court blesses an action as radical as the Japanese internment, pointing out that “once a judicial opinion rationalizes such an order to show that it conforms to the Constitution, or rather rationalizes the Constitution to show that the Constitution sanctions such an order, the Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination in criminal procedure and of transplanting American citizens. The principle then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.” Jackson cautioned that “a military commander may overstep the bounds of constitutionality, and it is an incident. But if we review and approve, that passing incident becomes the doctrine of the Constitution. There it has a generative power of its own, and all that it creates will be in its own image. Nothing better illustrates this danger than does the Court’s opinion in this case.”

Finally, Jackson warned that the “chief restraint upon those who command the physical forces of the country, in the future as in the past, must be their responsibility to the political judgments of their contemporaries and to the moral judgments of history.”

This brings us to the dissent penned by Justice Frank Murphy, who wrote that the exclusion of both alien and nonalien Japanese “goes over ‘the very brink of constitutional power,’ and falls into the ugly abyss of racism.” Noting that the internment order “deprives all those within its scope of the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment.” He contends that “no reasonable relation to an ‘immediate, imminent, and impending’ public danger is evident to support this racial restriction, which is one of the most sweeping and complete deprivations of constitutional rights in the history of this nation in the absence of martial law.”

And then Murphy arrives at the analysis that still today offers a clarion call to David Bowers and the many, many David Bowers across the land who have used the events in Paris to call for vicious callousness to the plight of Syrian refugees: “To infer that examples of individual disloyalty prove group disloyalty and justify discriminatory action against the entire group is to deny that, under our system of law, individual guilt is the sole basis for deprivation of rights. Moreover, this inference … has been used in support of the abhorrent and despicable treatment of minority groups by the dictatorial tyrannies which this nation is now pledged to destroy. To give constitutional sanction to that inference in this case … is to adopt one of the cruelest of the rationales used by our enemies to destroy the dignity of the individual and to encourage and open the door to discriminatory actions against other minority groups in the passions of tomorrow.”

Bowers’ statement about Syrian refugees ends with the caution that “at least for awhile into the future, it seems to me to be better safe than sorry.” But maybe before he calls for group reprisals and racial stereotyping, he should reread these words from Murphy’s Korematsu dissent as a cautionary tale. They are as resonant today as they were in 1944: “I dissent … from this legalization of racism. Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life. It is unattractive in any setting, but it is utterly revolting among a free people who have embraced the principles set forth in the Constitution of the United States.”