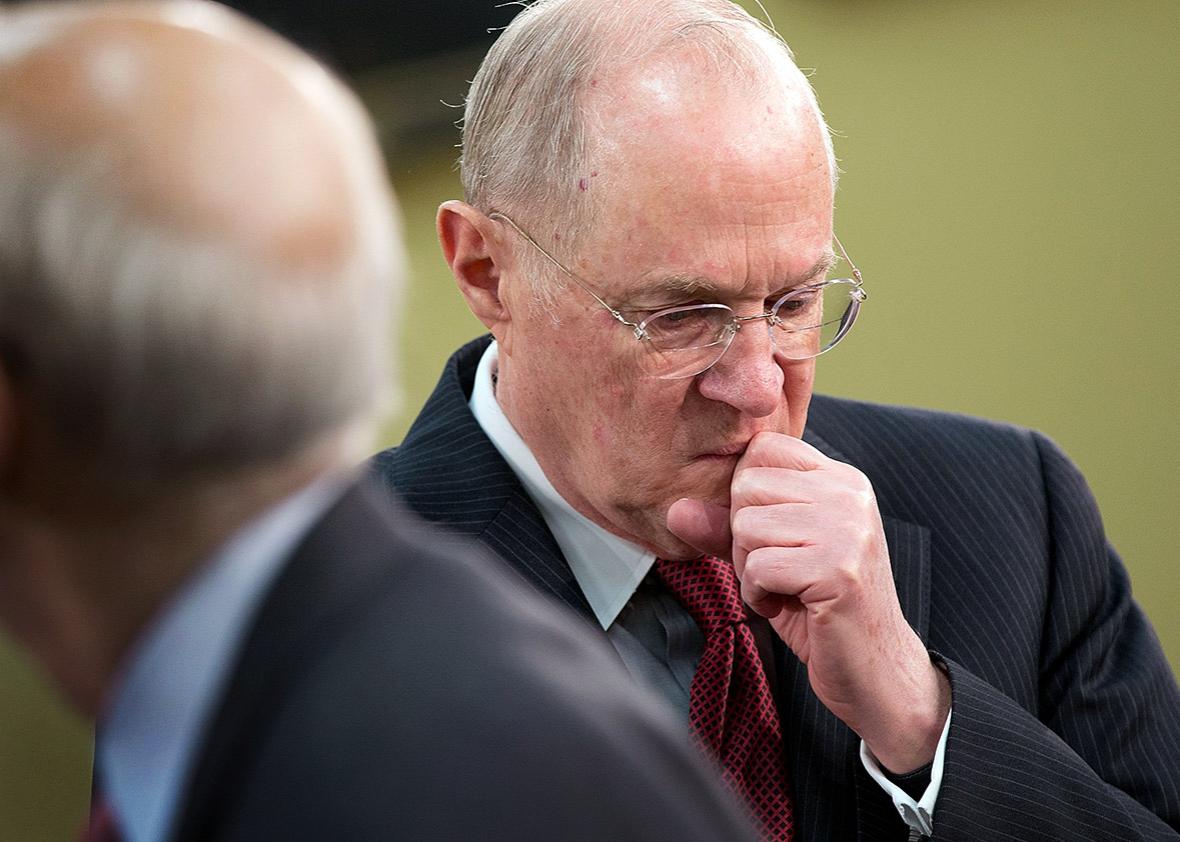

Ever since the court announced on Friday—after eight years of silence on the issue—that it was going to hear a major abortion case, all eyes have been fixed on Justice Anthony Kennedy. He will certainly be the decisive vote in Whole Woman’s Health v. Cole this summer. On this issue, among so many others, it’s a foregone conclusion that wherever Kennedy goes, the court will follow.

It is hardly an exaggeration to say that Cole will be the biggest abortion case the court has heard in decades, and its ruling on HB 2—Texas’ huge omnibus abortion bill from 2013—will determine whether Roe v. Wade is still the law of the land or the remains of a hollow promise. Already parts of the law that have gone into effect have reduced the number of clinics in Texas from 41 to 18. And if the court approves the two Texas restrictions at issue in Cole, there will be nine clinics left to serve a population of 5 million women of reproductive age.

Now, those of us who watch Kennedy in exchange for a paycheck tend to be conflicted about the signals he has sent on reproductive rights. Some, like Ian Millhiser of ThinkProgress, are heartened by the fact that Kennedy voted to grant a stay preventing HB2 from immediately going into effect, which might suggest that he at least understands that the shuttering of 75 percent of Texas clinics is not a trivial matter. The fact that he twice joined with the four more liberal justices to keep parts of HB2 from going into full effect before the court could look at it means that he takes its consequences seriously.

The stakes in this case go far beyond the admitting privileges and ambulatory surgical center requirements at issue; they go to the very core holding in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 case establishing that the constitutional right to abortion could not be encumbered by state regulations that have no real connection to a legitimate state purpose. States may not put an “undue burden” on the right to terminate, even if that phrase remains completely incomprehensible. And as Jessie Hill wrote in September, “Kennedy, one of the authors of the joint opinion in Casey, must think ‘undue burden’ means something, and the facts in the Texas and Mississippi cases, in particular, are extreme. If he is ever going to find an undue burden is imposed by a purportedly neutral health regulation, it is probably going to be in a case like these.”

But on the other side of the scales, many court watchers note that Kennedy is not a fan of abortion and that it’s a mistake to believe he teeters at the center on this issue. In an important article he wrote for Slate two years ago, David S. Cohen debunked the myth that Kennedy is a moderate on reproductive rights, pointing out that since he joined the high court in 1988, “the so-called swing justice, Anthony Kennedy, has voted to strike down only one of the 21 abortion restrictions that have come before the Supreme Court.”

It’s almost impossible for anxious Kennedy watchers to ignore Kennedy’s visceral horror of abortion procedures. As Cohen observed, Kennedy’s language in the post-Casey abortion cases is not equivocal: “Kennedy’s dissent uses language straight out of the anti-abortion movement’s talking points. He calls the doctor an ‘abortionist.’ He calls the fetus ‘unborn’ life. He calls the abortion procedure at issue one that ‘many decent and civilized people find so abhorrent as to be among the most serious of crimes against human life.’ ” By the time Kennedy was writing the majority opinion in 2007, in the so-called partial-birth abortion case Gonzales v. Carhart, he was comparing the medical procedure at issue to “infanticide.”

It makes sense to consider Kennedy’s own feelings and personal horror about abortion when imagining how he will approach whatever remains of the “undue burden” test. But there is another imperative for Kennedy that may also be at work as he thinks through the possibility of functionally overturning Casey and Roe. And that is how Justice Kennedy thinks about the act of making choices itself.

Consider what was perhaps the single most revelatory interview Kennedy ever gave, his 1992 explanation to a reporter from California Lawyer, on the morning Casey was to be handed down, in which he mused aloud that: “Sometimes you don’t know if you’re Caesar about to cross the Rubicon or Captain Queeg cutting your own tow line.” He then excused himself from the interview, saying that he needed to “brood.” We in the press love to send up Kennedy’s sense of himself as a great agonizer (indeed Jeffrey Rosen’ s 1996 profile of Kennedy in the New Yorker was titled “The Agonizer”), but the fact is that decisions about how people make choices are perhaps closer to Kennedy’s heart than any other decisions.

Kennedy thinks about how he makes his own choices more obsessively than any sitting jurist. In a 2005 interview Kennedy gave to the Academy of Achievement, he famously explained how hard decision-making is for him:

But after you make a judgment you must then formulate the reason for your judgment into a verbal phrase, into a verbal formula. And then you have to see if that makes sense, if it’s logical, if it’s fair, if it accords with the law, if it accords with the Constitution, if it accords with your own sense of ethics and morality. And, if at any point along this process you think you’re wrong, you have to go back and do it all over again. And that’s, I think, not unique to the law, in that any prudent person behaves that way.

Kennedy, in short, is never more Kennedy-like than when he is deciding about making decisions, and it’s why two of his constitutional watchwords are “dignity” and “autonomy,” the two words at the heart of Casey’s conception of liberty.

Those of us who were incensed at Kennedy’s paternalism in Gonzales v. Carhart, his last major abortion opinion, in 2007, took issue with his odd (and scientifically unsupported) fetish around “post abortion syndrome,” and his insistence that “it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained.”

This kind of language sent Ruth Bader Ginsburg herself into orbit in her dissent, scathingly noting that “the Court invokes an antiabortion shibboleth for which it concededly has no reliable evidence: Women who have abortions come to regret their choices, and consequently suffer from severe depression and loss of esteem.” Ginsburg went on to quote a 2006 study showing that “neither the weight of the scientific evidence to date nor the observable reality of 33 years of legal abortion in the United States comports with the idea that having an abortion is any more dangerous to a woman’s long-term mental health than delivering and parenting a child that she did not intend to have.”

One way to think about Kennedy’s unsupported obsession with helping women make decisions they won’t later regret is that he simply doesn’t believe women have the same kind of agency, autonomy, or common sense as men. The more benign version would hold that he wants to be certain that people can brood and mull and ponder and then change their minds, because he would like to reserve the right to brood and ponder and then change his mind. It’s not really an empowering or even a helpful position for the millions of women he attempts to help and empower, though. As Justice John Paul Stevens famously put it when considering waiting period requirements in Casey: “the mandatory delay … appears to rest on outmoded and unacceptable assumptions about the decision-making capacity of women.”

But if the downside of Justice Kennedy’s tendency to obsess and second-guess himself is a tendency to impute that same need onto all of womankind, the upside to all this brooding may still be that Kennedy, ultimately, believes that, in the end, dignity and autonomy require that one should be allowed to choose. That latter Kennedy was the one who showed up in the Obergefell marriage opinion: “The right to personal choice regarding marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy. … Like choices concerning contraception, family relationships, procreation, and childrearing, all of which are protected by the Constitution, decisions concerning marriage are among the most intimate that an individual can make.” Kennedy’s belief that people can make good autonomous choices was also at the core of his votes to bar sentences of life without parole for juveniles in most circumstances in 2010 and 2012.

If it is true that Kennedy believes that most people will, as he does, eventually make good choices for themselves, Texas’ abortion regulations at issue in Cole become ever more problematic. If, after Casey, an “undue burden” exists whenever “a state regulation has the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion,” there is no real doubt that the Texas regulations impose one. The district court in Texas originally held the law unconstitutional precisely because it would leave 17 percent of Texas women of childbearing age—900,000 of them—more than 150 miles from the nearest abortion provider. The panel of 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals judges who reversed that decision felt the regulations did not burden a “large fraction” of women, since 17 percent is “nowhere near” a large fraction. This is not a situation in which some significant number of women in Texas and other states with similar provisions will be afforded tools—like mandatory warnings or forced ultrasounds—that Kennedy might readily construe as helping them make better choices. This will simply mean that hundreds of thousands of women will have no choices, or the choice to leave the state and hope for better luck in New Mexico—an outcome also offered as a good alternative by the 5th Circuit.

In a recent article explaining how state maternal health justifications may undermine the core rule of Casey, Reva Siegel and Linda Greenhouse summarize the problem this way: “States may try to persuade women to choose childbirth, but may not obstruct them from acting on their decision to terminate a pregnancy. This distinction is crucial to Casey’s logic, and to the integrity of the undue burden framework as a compromise. A regulation that closes a clinic does not persuade a woman to forgo an abortion; it prevents her from obtaining one.” For all their conceptual flaws, both Roe and Casey were choice-affirming decisions. And Kennedy clearly believes that vulnerable women should have lots of information and hedge against any possibility of future regrets in making their difficult choices. But it strains credulity to imagine that he will happily accept the argument that the best way to ensure that brooding, uncertain women make good decisions is to ensure that they cannot make any.

Finally, even if the choice-affirming Justice Kennedy doesn’t have much confidence in the powers of Texas women to make good choices, it’s hard to imagine that he would be perfectly sanguine about the fact that the “health reasons” offered up by the state to justify the new regulations in no way correlate to better health outcomes. The 5th Circuit panel chose to defer completely to the state Legislature’s claims that the two provisions make women healthier, even though there is precisely zero support for that proposition anywhere in the mainstream medical community.

So perhaps the hardest question for a Justice Kennedy who believes that autonomy rests in the power to make wise, well-informed choices will be whether he is willing to tolerate transparently pretextual rationales for the Texas rules, under the guise that legislatures always know what is best for maternal health. Sometimes legislators even forget themselves and admit to their real purposes. As Greenhouse and Siegel note, “shortly after the Texas admitting-privileges and ambulatory-surgical-center bill was sent to the House, then-Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst tweeted a photo of a map that showed all of the abortion clinics that would close as a result of the bill, writing ‘We fought to pass SB5 thru the Senate last night, & this is why!’ ” (Dewhurst quickly realized he had proudly crowed about an intentional undue burden and reversed himself, tweeting, “I am unapologetically pro-life AND a strong supporter of protecting women’s health. #SB5 does both.”)

What Justice Kennedy will do with the competing legal values in Cole is anyone’s guess, and he may well still be crossing the Rubicon in his own mind right down to the last days of June. But as difficult as Kennedy’s decision will be for him, it’s hard to imagine that he would ever withhold from half the population, the basic freedom he most cherishes: the freedom to think about it, to maybe even get it wrong, and to keep on going.