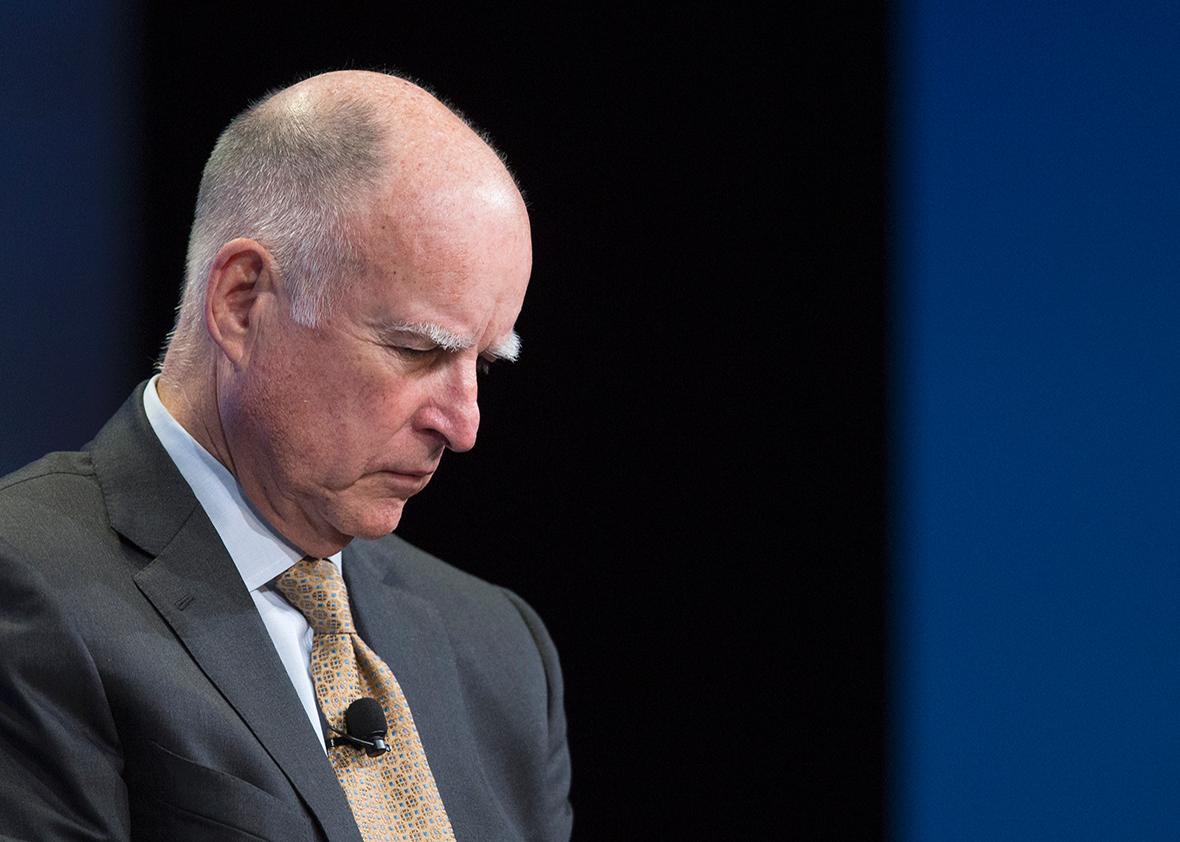

This week, California Gov. Jerry Brown, a former Jesuit seminary student, signed the End of Life Option Act. The new law will permit Californians to obtain prescriptions for lethal doses of painkillers if they are suffering from a terminal illness. Brown was clearly deeply conflicted as he signed off on the controversial legislation, which will make California the fifth state to pass a physician-assisted suicide law after Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Vermont. This is of huge consequence to backers of the right-to-die movement because once California’s law goes into effect in early 2016, 1 in 10 Americans will live in a state that would permit terminally ill patients to end their lives. Twenty other state legislatures have been considering this type of legislation

As the New York Times notes, the law attempts to build in substantial protections for patients: “Two different doctors must certify that the patient has six months or less to live before prescribing the drugs, patients must be able to swallow the medication themselves, and they must be of sound mind and not under coercion from their families. Hospitals and doctors can decline to participate.”

It was unclear right down to the wire what Brown would do with the bill. Calling it a “gut-wrenching” decision, Brown carefully read all the opposing camp’s arguments, consulted with a Catholic bishop, his own doctors, and former classmates and friends, as well as with Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He also spoke to the family of Brittany Maynard, a cancer patient who chose to end her own life in Oregon last year, when California did not permit her to do so.

What is most singular and striking about Brown’s personal and conflicted signing document is the extent to which he attempts to reconcile the best arguments against the bill—particularly the religious and theological ones—with his sense that he cannot be certain that, were he in the same situation, he would not want the right to end his own life. As he put it:

I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.

There are so many things about this simple statement that are remarkable, chief among them the humility of a lawmaker attempting to imagine himself into a scenario that is heartbreaking and tragic. Compare it to the moral certainty of legislators who would deny a woman the right to end her pregnancy, even in cases of rape or incest, without giving a moment’s thought to the possibility that it could happen to them, or their daughters or wives. Compare it to the moral certainty of putative political leaders asserting that they know exactly how they would behave in a mass shooting.

What Brown’s statement achieved, in just three eloquent sentences, was a model for what lawmakers should do in contemplating legislation that, as Brown notes, deals with “life and death.”

Contrast Brown, and his efforts to imagine himself or his family confronting the unimaginable with Lindsey Graham, the South Carolina senator who voted against disaster relief for victims of Hurricane Sandy, then asked for federal aid this weekend after his own state was flooded by Hurricane Joaquin.

Because when disaster strikes other people, they’re moochers and suckers, but when it happens to you, it’s tragedy.

Brown’s simple thought experiment—that having weighed all the arguments, he can’t be certain that he wouldn’t choose this option himself in a crisis—is not complicated or difficult. Imagining ourselves in another’s position is a thought process most of us go through every day when dealing with our friends or our family. But it’s become something of a point of pride among legislators to pass judgment first, and moralize later, without ever doing the simple work of asking: “But what if this were me?”

We have become accustomed to seeing legislators change their views on an issue when they face it directly—endorsing marriage equality after a family member comes out is a good example. That’s nice, but that is not what Brown did this week. He wasn’t saying, “I have new sympathy for a political position because I now realize what human suffering feels like.” He was saying, “I have no idea what this suffering may feel like but I am not in a position to judge.”

What’s staggering about Brown’s statement isn’t how much he grappled with a thorny ethical question with profound theological implications. That in itself would be novel in this political climate. But the truly amazing thing is the fact that he struggled and concluded that he couldn’t imagine what he would do in the face of a tragedy. That kind of admission has become all but unthinkable in political discourse today. The sooner our lawmakers learn that they can’t know what the unimaginable will look like, the more likely they are to start passing laws crafted for the messy lives we lead, and not the lucky lives they demand.