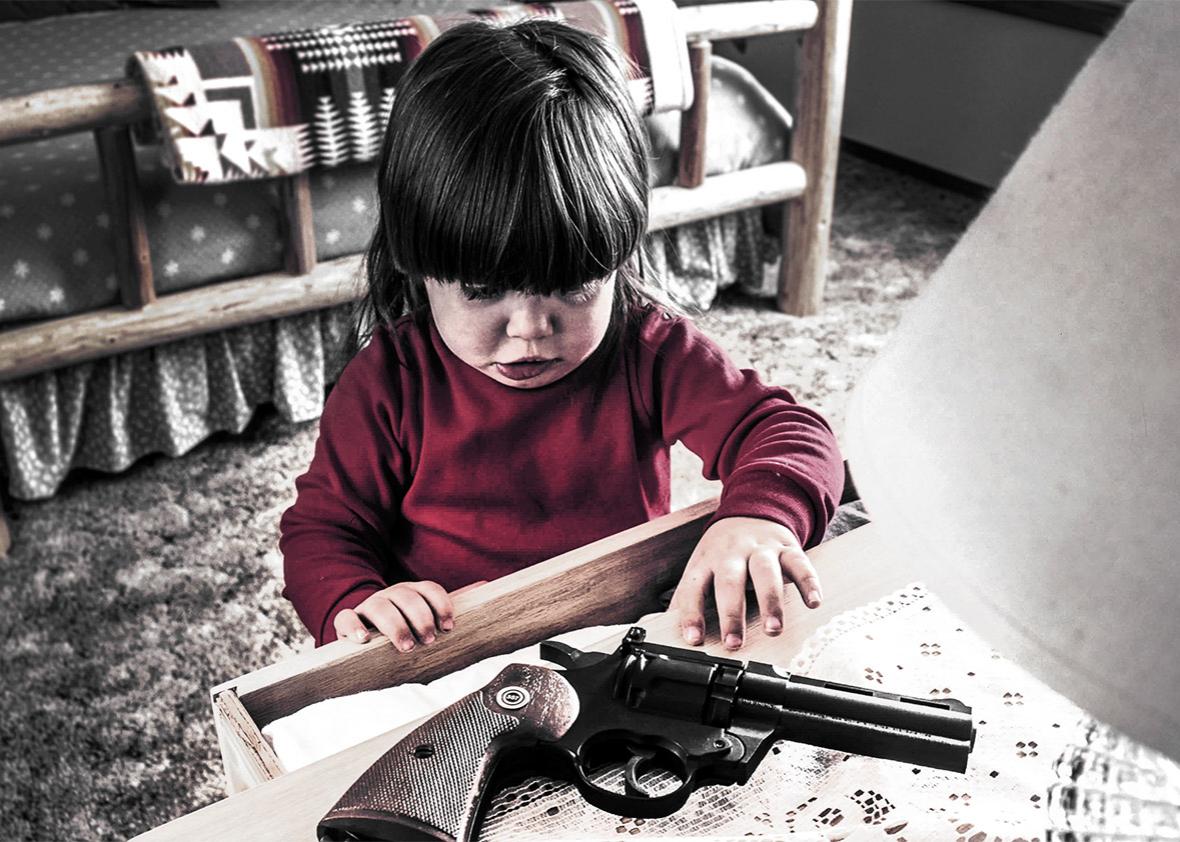

Last week, in what’s actually become a pretty standard week in America, two young children shot two other children dead with unsecured guns. Nothing about this is a surprise, really—89 percent of unintentional shooting deaths of children take place in the home, when children are playing with a loaded gun while their parents are out. American children are 9 times more likely to be killed by a gun than are kids in other developed nations. There are more than 310 million guns in the United States, and more than 30 percent of Americans report that they have a gun in their home. Those guns are not always stored securely. A RAND Corporation study showed that about 1.4 million households (with an estimated 2.6 million children) had firearms stored unlocked and either loaded or with ammunition nearby.

A pretty standard week in America. Sunday, a 2-year-old in South Carolina shot his grandmother in the back while he was riding in the backseat of a car. He found the .357 revolver in the pocket on the back of the front seat and fired the weapon.*

Studies show that while most parents and grandparents and friends believe their weapons are safely hidden, children as young as 3 know where to find them and how to use them. We can’t make our children stupider. But we can encourage parents to make sure their guns are secured. Cruel as it may sound to prosecute a parent dealing with the fallout from an accidental shooting, holding adults accountable for failing to lock up their weapons would at the very least create an incentive for them to be less careless.

The number of gun deaths resulting from child shooters has been dramatically undercounted, so it’s difficult to establish a proper tally. But estimates suggest that more than 100 children die this way each year, and more than 3,000 children are shot unintentionally. And most of the shootings by children—more than two-thirds—would have been prevented had the gun owners stored their weapons properly. Last week, after an Ohio boy accidentally killed his brother, Dan Savage angrily highlighted the last line of a news account explaining that nobody was charged: “That last sentence. Until that changes, this won’t.”

He’s right. Someone needs to be responsible when children kill children with unsecured guns. Gun makers enjoy extraordinary freedom from liability when gun accidents occur, and that means gun owners bear most of the legal burden. Twenty-eight states have what are known as “child access prevention” laws, which impose criminal liability on adults who negligently allow kids to have access to their guns. States with these CAP laws show reductions in both accidental shootings and child suicides. But as Justin Peters has argued many times here at Slate, these CAP laws are almost never enforced, in part because they are vague, and in part because prosecutors have no heart to punish parents who have already suffered unimaginable pain when their child killed another child, often their own.

Even in states where these laws exist, they’re both inconsistent—standards and penalties for culpability vary widely from state to state—and inconsistently applied, with prosecutors often choosing not to pursue cases against negligent parents out of sympathy, perhaps, or a sense that these cases are hard to win. And that’s understandable: These shootings are tragedies, after all, and why compound a family’s misery by sending a grieving parent to jail? But CAP laws are only effective as a deterrent if they’re vigorously enforced.

Writing last April in the New Republic, Amanda Gailey noted that Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit that aggregates media accounts of gun violence, verified that there were more than 1,500 accidental shooting incidents in 2014—and that there are accounts of dozens of unprosecuted unintentional shootings from the first two months of 2014 alone.

It surprised me that there were laws on the books that might have prevented these shootings but little political will to enforce them. So I spent a few days last week confirming with various prosecutors what has already been demonstrated in media accounts from Texas, California, and Minnesota: even where CAP laws are in place, prosecutors are loath to go after parents who have already suffered. In fact, when the first CAP law was passed in Florida after five children were involved in accidental shootings in a single month in 1989, state Rep. Joe Johnson, a Democrat, told the Miami Herald he didn’t support “putting grieving parents in jail.”

Paradoxically, the states in which parents are not charged for improperly storing their weapons may end up being the states that charge young children as murderers. That’s what happened last year in Michigan and last week in Tennessee. It’s extraordinary that we are more willing to retraumatize an 11-year-old than to retraumatize his parents.

And so I spent the week asking prosecutors why they thought CAP laws aren’t enforced. Their responses echoed the media narrative: No jury would convict someone who had already suffered such a loss, and accidental shootings, even those in which weapons were improperly stored, are largely viewed as misfortune rather than misconduct in many places. These are elected positions, and there is very little public appetite for such prosecutions. As Robert Weisberg of Stanford Law School explained to me in an email, it’s easier to go after negligent parents for leaving their children in a hot car than for leaving their gun accessible: “Ironically, [hot-car cases] are prosecuted more often than the gun cases and often lead to some Child Protective Services intervention.” Heck, we go after parents who let their children walk through the neighborhood more aggressively.

Weisberg thinks that’s because we have trouble understanding negligence when it comes to guns. “There’s nothing antisocial per se about the background fact of keeping kids in a car,” he points out; the problem comes about when the parent forgets the kid is there. Similarly, many Americans just don’t think of parents who leave guns lying around as negligent because, as with cars, “there is never any abstract risk with having guns in the house, nothing the least antisocial about it. Storing a gun is not only normal life—it’s better than normal life if we see it as sacred or a form of home defense.”

Because so many people refuse to think of guns as inherently dangerous, the NRA and the gun industry are comfortable arguing that the best way to prevent kids from shooting kids is by teaching children to shoot, and by marketing weapons for children. The gun itself is not the problem, even in the hands of children; the gun is—in this view—the solution.

Of course Justin Peters is right that CAP laws should be enforced. There is no other way to ensure that parents take seriously the legal obligation to secure their guns. And Dan Savage is right: Barring such enforcement it’s hard to imagine that we won’t keep seeing two children shoot two other children every week. But most pointedly, until we can stop thinking that locking up people who fail to lock up their guns is some kind of double assault on liberty, we will continue to live with “accidents” that were almost entirely foreseeable and preventable.

*Correction, Oct. 13, 2015: This article originally misidentified the state where a 2-year-old shot his grandmother from the backseat of a car. It was in South Carolina, not North Carolina. It also misstated what kind of gun the 2-year-old used. It was a .357, not a 357. (Return.)